Foraging is more than a hobby. It’s a means of sustenance, and for some of us, it really is a way of life. Pretty much everyone has an idea that some wild plants are edible whether they work in a city high-rise or hoe weeds on the farm. Even in this strange modern age, many of us have childhood memories of finding a cache of wild strawberries, chewing on sour grapevine tendrils, or getting scratched while picking blackberries.

Watch the Video:

But when you become an adult, life becomes complicated. We learn about liability and risk, we try not to trespass on land that’s not ours, we hear about ecology and threatened species, and some of us eat out for every meal because we’ve found ourselves living a hectic, stress-filled life. We end up distant from understanding the plants that surround us. And suddenly, if your young child grabs your hand and tugs you toward a loaded berry bush, you may find yourself pulling them back, muttering “What if it’s poisonous?” or “Leave it alone! — we’ll get food later.”

If those words catch in your throat (or if you were that kid), this article is for you. The truth is, there is abundant wild food out there that is nutritious and free and absolutely delicious. I know many of us haven’t grown up with parents or a community who foraged routinely and taught us the ropes. Many of us might not be sure where to look or how to get started, or even how to know which plants are safe. But after reading this article, I hope to help set your feet on a good path toward understanding and the beginning of your own foraging journey.

The Poison Hurdle

When it comes to beginning foraging, the first matter of business is proper plant identification. Though the number of people who have poisoned themselves with wild plants is minuscule compared to the generations of folks and cultures who have eaten and thrived on them, there are poisonous plants out there, and it’s the job of any forager to know how to identify them and, of course, not eat them.

But before we get into the how to identify, let’s cover the very important part of how to approach wild plants in general. There’s inherent risk with any activity but the specter of poison has created two very extreme and erring sides on the beginner’s foraging spectrum.

On one side are the terrified. These are the folks still suspicious that every plant is so potentially poisonous that they can make themselves feel literally sick…even if the food was safe and correctly identified. As anyone who has struggled with anxiety knows, it makes you feel nauseated and panicked, and those symptoms are easy to assign to imagined poisoning. Worry saps the flavor out of any meal and keeps you from progressing in knowledge, however. I suppose the irony on this side of the spectrum is these people probably never get poisoned–they can’t, since they’re too worried that that clump of wild strawberries might, just might, be a deadly nightshade bush in disguise (spoiler alert: it’s not.).

On the other side are the throw-caution-to-the-wind folks (or unsupervised children). Armed with anecdotes, vague information, and bragging overconfidence, they’ll eat a plant … even if their identification is lacking. When others are watching and you want to show off your wilderness prowess, it’s easy to declare yourself an “expert” because you read a book or article once and know a few more facts than your audience (I’d exercise caution around anyone who declares themselves an expert, by the way). These are the ones who may tragically poison both themselves and the reputation of foraging; adding fuel to the fire of our western culture’s complete disconnect and overblown fear of the natural world.

Your job is to be in the thoughtful, well-informed middle. To neither make the assumption that every plant could hurt you, nor the assumption that no plant could hurt you. And that starts with knowing a thing or two (or 20) about the plants you hope to eat. Let’s talk about how to get started.

How to Properly ID a Plant

In order to forage, you need to be willing to learn a lot about plants. Not just their names, but their parts, growing seasons, preferred habitats, and any idiosyncrasies. Taking the time to really learn your foraged food will allow you to follow the single most important rule in foraging: Never eat a plant unless you are 100% positive of its identity.

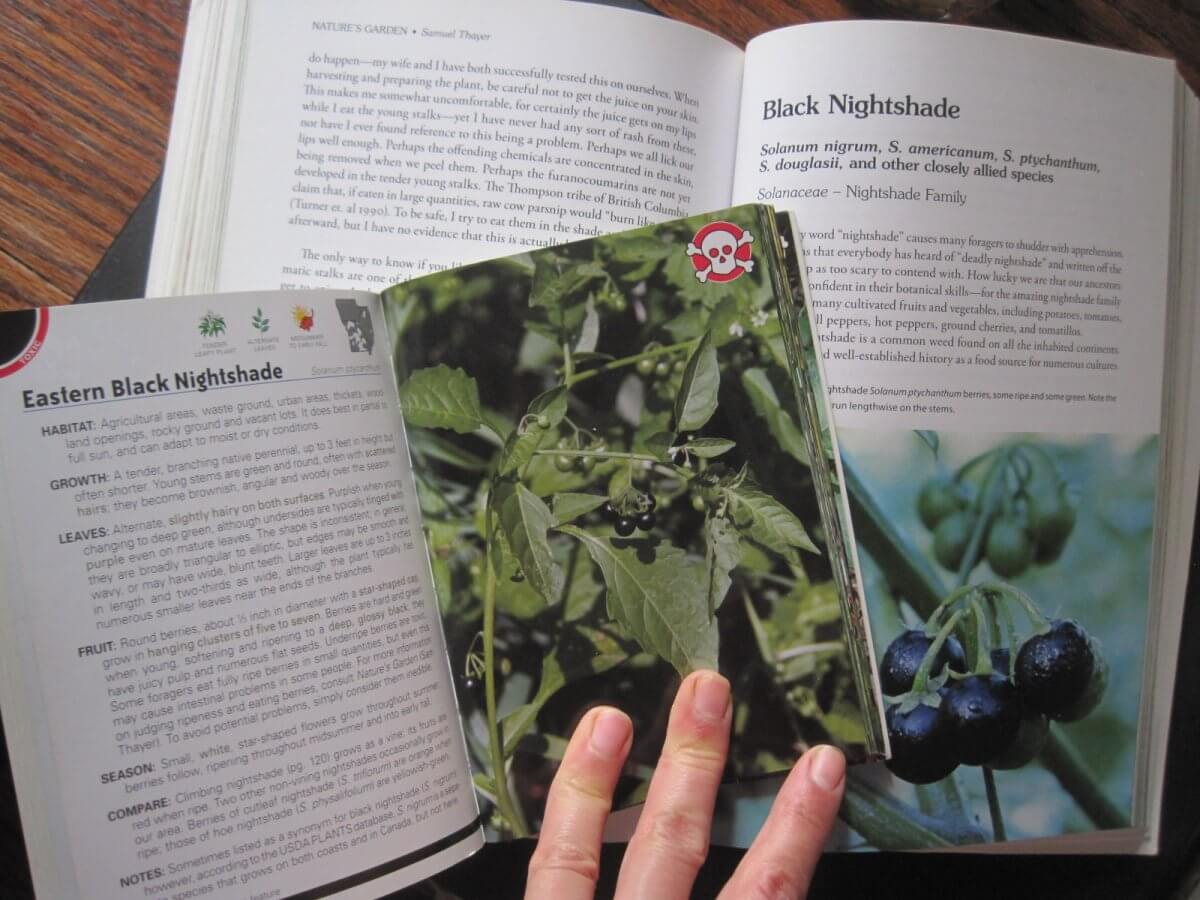

Samuel Thayer has written a 5-step process for plant identification that’s just so spot-on I couldn’t improve it. Here’s a summary of the process I’ve learned from his books and use myself in the field.

1. Tentative Identification

This is when you find a plant, and think you know what it is. This is the beginning of an identification process, however, not the only part of it.

2. Reference Comparison

Now, take some time to inspect your potentially-identified plant. Compare it to the guide book that introduced you to it in the first place, and read through the description carefully. Make sure that every point listed matches, particularly ones that are emphasized as key features. If it doesn’t match, don’t force it to match. And if you don’t understand all the botanical lingo, don’t gloss over it. If you lazily TLDR a plant description because the terms are unfamiliar, you put yourself in unnecessary danger. Learn what an umbel, a bract, a petiole, and a raceme are (and so on) because these are crucial tools for positive identification. Finally, never use a single feature as the only identification confirmation.

3. Cross Referencing

Run through step No. 2 with at least two other foraging resources or field guides. Read carefully about potential look-alikes. Make sure you have triple-confirmation on your plant’s identity.

4. Specimen Search

Go find lots and lots of samples of your potentially identified plant in the field. As you know (or as you’ll learn) the environment can totally change how a plant grows. A dandelion growing directly in a sunny field, for instance, will produce feathery, deeply-toothed leaves that lay almost flat on the ground. A dandelion growing in a shaded area will grow wide leaves that point upwards. You’ll need to learn the range in variability for your target plant so you can develop your recognition beyond the single photo in the guide book. This process may take an hour, or it may take years.

5. Contradictory Confidence

This is the deep-seated confidence that means you can recognize and positively identify a plant as food, even if someone were to try to convince you otherwise. That’s how well you should know a plant before you eat it. If there is a shred of doubt about a plant you have found, use it as a red flag that it’s not time to eat it yet. This is perhaps the most difficult level of identification to achieve, but one of the most crucial. With some plants, it may take years to grasp. Take that time. I still have many plants at this step — though I can find them, I don’t have complete confidence if someone were to challenge me on it, and I still haven’t eaten them.

New Forager Tips

Don’t Overindulge

Anyone who has gorged on ice cream knows the nausea that accompanies an overindulgence. No one would say you’ve been poisoned by ice cream, though! Wild foods also need to be eaten in rational amounts, even if you’ve found enough to feed an army. Err on the side of caution, particularly with a new wild food. Eat a small amount and see how you respond to it.

Listen to Your Body

You should listen closely to the physiological cues your body gives when you’ve ingested a small sample of a new plant for the first time. If you’ve done your homework, cross-referenced, and identified it correctly, you’ll be fine and nothing will happen except the satisfaction of finding a new food. But on the off chance that you start salivating uncontrollably, feel a burning sensation in your throat, find it unpalatably bitter, feel nauseated, or can’t stomach the flavor, spit it out. Your body is telling you something’s wrong. Maybe the plant was misidentified, maybe it is the wrong time of year to eat it, maybe you’re allergic or something else is going on. Obviously, don’t eat any more of that plant. Instead, take several photos or a sample to research why your body reacted, and make sure you learn from your experience. If misidentification is the culprit, naturalists at local departments of conservation can often offer positive identification of local plants.

Right Plant, Right Time, Right Way

Wild plants are much like any other domesticated plant. They taste best and are most useful when the right plant is used in the right way at the right point in its growth. Think about the difference between eating a perfect avocado (the best!) and an avocado that’s a week too old. Or consider the potato — not so great raw, amazing when cooked. Wild plants likewise have windows of prime palatability and safety. Since we in the West don’t have a huge cultural tradition of using wild plants, you’ll have to go on a personal quest to meet and know every wild food you add into your foraging repertoire. Read carefully about when it is best to harvest a wild plant during the growing year, and how it’s best to prepare it.

Where to Find Wild Food

Your Own Land

Of course, the easiest and most accessible place to find wild food is your own land, and you don’t need a back 40 to have enough. Even a postage stamp in the city can grow a surprising array of food to forage if you know what to look for.

If you find wild plants that you particularly enjoy, there’s no reason you can’t plant them on your property and maintain your own patches of undomesticated goodness. You can obtain seedlings and bare-root trees of many edible native plants from your state’s department of conservation.

Related Post: Foraging For Wild Berries

Other People’s Land

This is an option for the bold and polite only. While driving through the city or country, you may find a field or area totally loaded with promising looking food that no one seems interested in. A stand of wild asparagus, a thicket of wild plum, a pecan tree dripping with nuts, a pond nodding with cattail. Be proactive and thoughtful, and ask the landowner if they would allow you to gather wild food from their land. Accept their answer, whatever it is, with no contest. If they do agree, be sure to offer to share some of the haul with them — they’ll appreciate the gesture even if they think you’re a bit nuts. If you don’t do damage and are respectful, you’ll likely be able to make a repeat visit the next season, or maybe make a friend.

Never forage on someone else’s land without asking.

Other Land

This is a dodgy and confusing subject as the rules and laws governing foraging are anything but clear or consistent. At the city, state, and national level, you’ll find everything from full-scale prohibition to vague allowance. You’ll find outdated laws that ban native peoples from gathering foods in their traditional gathering places, and park visitors fined for gathering berries, but you’ll also find nature programs that teach and encourage foraging, as well as activist groups fighting for peoples’ rights to enjoy wild food as a means of conservation. Online debates rage, some accusing any forager of destroying shared natural spaces, others explaining that foraging actually improves the land when done responsibly.

Every national park, nature preserve, city park, and state forest has its own rules. Some allow foraging, some have restrictions in place limiting how and how much you can gather, some ban it entirely. So what’s an interested forager to do? There are a couple of options.

First, you could start by looking for foraging programs offered at nature centers and parks. Not only are these excellent opportunities for firsthand instruction, they give you an opportunity to locate some areas deemed acceptable for foraging.

You could also call ahead to the leadership at a park or forest that you’re interested in exploring, and see if they allow foraging. It’s likely you’ll get some disappointing responses, but call anyway. Find out what edible invasive plant is common in these natural areas. Good candidates include garlic mustard, autumn olive, kudzu, and field garlic. Ask if you could help with conservation by foraging for (and removing) these plants to help support the recovery of native plants (and make sure you know enough about these plants to back up your claims, of course). Sometimes they have volunteer task forces specifically aimed at that goal. It will you help reinforce the positive good that foraging can do, and you will have an endless supply of these plants open up to you.

You could also scope out fruit and nut trees in public spaces ahead of time, and watch for when they’re ready to harvest. In many more urban areas, these trees are seen as a messy nuisance. Ask someone who works in a building on the property if you can help yourself to the unwanted bounty of mulberries, walnuts, persimmons, acorns, or apples. Many people are more than willing to have their sidewalk-staining problem cleaned up.

Wherever you decide to forage, and whether you get involved in petitioning local authorities for more freedom or work out a deal with a local park, do it neatly, responsibly, and thoughtfully. Foraging has been given an unfairly bad reputation by many well-meaning (but often ignorant) conservation-minded people who claim that we’re destroying the areas we harvest. The reality is that most of us really care for and protect our foraging sites. Don’t give them fuel for their fire by making a mess, leaving holes, or selfishly wiping out entire areas of roots, bulbs, and rare plants.

Related Post: Foraging for Pokeweed

Where to Avoid

Not everywhere is safe for foraging, however. As you go plant-hunting, avoid harvesting from the following areas.

Manicured Public Spaces

Along the sidewalk in town, in the strip of grass beside the post office, around the gazebo in the town square, in the lawn at college, there are plenty of plants growing. These areas, however, are spaces I would strongly advise avoiding. Areas that are in full public view and aren’t reserved as a wilderness or nature area, are almost certainly contaminated. Businesses really don’t like the dandelion growing through the sidewalk, the chickweed sprawled at the side of the building, or the clover in the lawn, and will usually employ whatever chemical means necessary to improve the look of their establishment. The only wild food that might be safe in these environments are tree nuts and fruits.

Under Powerlines or Around Utilities

Power companies don’t like plants growing around their lines, and will often spray toxic pesticides directly under and around them to keep the spaces clear.

Roadsides and Parking Lots

Cars generate and leak tons of chemicals onto the ground, and this contaminates the areas directly bordering roads. The concentrations of lead along roadways built before the advent of unleaded gasoline can be surprisingly high. As such, avoid plants growing downslope of roads or directly bordering parking lots.

Industrial Areas and Contaminated Ground

An amazing feature of many plants is their ability to uptake toxins from the soil and clean it in ways that no human-powered crew could (this process is called bioremediation, and it’s fascinating). It means, however, that many mineral-rich plants such as clover and wild spinach could easily be contaminated if they are growing in toxic ground. Industrial areas, dumping sites, and any other place potentially contaminated with chemicals are places to avoid.

Make Sure Your Teachers Practice What They Preach

Foraging has recently increased in popularity as the internet has made information on it more widely available. I have personally been grateful for the information available in modern sources, as it set me off on this journey ten years ago. And though I’m glad to see people discovering healthy food and being outdoors, I have become increasingly perplexed and disturbed by the inaccurate and wrong information that has sprung up alongside all the good stuff. You can see everything from misidentified pictures, bad advice, and recipes that don’t seem possible.

Not everything online is true. Not everything in a book is true. So how do you figure out what is? I would advise to only trust a resource if the writer has worked with and eaten the plant they’re talking about. This may seem obvious, but you would be surprised how many resources have sprung up online and in print that don’t check that one, simple requirement. It’s a huge deal, and far too easy for a writer to make ignorant errors when experience doesn’t back them up. And since foraging remains a niche interest, the publisher may not have caught the misinformation. Obviously, bad teaching could have bad consequences. Use these four guidelines to vet a potential new teacher.

- Make sure they have photos of the plant — and specifically, photos they have taken themselves.

- Make sure they use the scientific name of the plant they’re discussing. Many plants go by several different names, and sometimes different plants go by the same name. It’s too easy to get identification crossed when you only use a local common name.

- Make sure the article or author teaches you what specific parts of the plants to use, and during what part of their growth. Some plants are only edible or palatable at certain points of their growth, and not every part of every edible plant is safe.

- Use caution when writers talk about the plant in vague terms, sharing “What they’ve heard” or “What has been said.” They should have plentiful firsthand information about a plant. And be sure to use that same caution when medicinal uses of a plant are shared. Often, people don’t have experience using them for healing and are copying information they read elsewhere. That certainly doesn’t mean the information is bad, but you should use it as a touchstone for further research, not as a trustworthy fact on its own.

With all that said, I can vouch that the resources I list for this article come from foragers who eat what they teach. I also promise that every plant I write about will be one that I have gathered and eaten personally. Even so, don’t take my word for it. You need to learn for yourselves, and use a non-fearful, yet discriminating eye on whatever you read.

Some Helpful Resources

Websites

This is a very incomplete list of good websites (a much better list is here), but it’s a good start.

Insteading: We have an ever-growing list of articles on foraging here!

Books

Books by Euell Gibbons, the granddaddy of modern foraging

Foraging is an endeavor you can begin in a weekend, and continue refining for your entire life. Being able to interact with the wild on such a direct level, transforms the landscape from an inert green expanse to a wild garden that you know and understand more and more each year. It can also cultivate love for those spaces — a sort of love that makes foragers some of the most surprisingly involved and passionate conservationists and naturalists in the world. When you bring home a full bowl of free food that you didn’t plant and cultivate, it can seed an incredible gratitude in your heart as well.

So maybe this summer, instead of tugging your child away, you can grab their hand and accompany them to those blackberry brambles, and together enjoy some of the best food in the world.

Leave a Reply