When you imagine a “garden,” what comes to mind? Ripe, red tomatoes? Golden stands of jewel-like corn? Green beans, squash, potatoes, and peppers? These typical food plants all originated in the amazing gardens of ancient Native American gardeners. Much has been written about the mysteries of how teosinte was domesticated into impossible-to-self-propagate modern corn, or how the Incas bred a surprising rainbow of potato colors and textures.

What we don’t often hear, however, is the complete list of interesting, nutritious, and perfectly adapted plant species that were developed or foraged as food in ancient soil. I don’t know if that list is possible to fully compile, but what I do know is there are a lot of delicious, nutritious, easy-to-grow and easy-to-find plants that deserve a lot more time in the limelight than they are currently given. You may have never heard of these plants before, but if you grow food in any of the Americas, you may find they grow in your gardens or fields like they belong there.

Tepary Bean (Phaseolus acutifolius)

Phaseolus vulgaris was the plant Indians domesticated to give us the mind-bogglingly huge world of pole beans and bush beans. But that species wasn’t the only legume they welcomed in their gardens. Tepary beans (Phaseolus acutifolius) are a less well-known bean that was and is primarily grown in the deserts of South America and certain parts of Central America (specifically Mexico) by nations like the O’odham. These beans are the most drought-resistant plants I’ve ever encountered, able to make a harvestable crop with the runoff from a single storm. They are a bit smaller and sweeter than common beans, but absolutely delectable, meaty, and hearty. You can read more about these amazing plants (and purchase your own seeds) over at Native Seeds Search.

They’re productive plants, too. Rabbits destroyed the majority of my seedlings the first year I planted tepary, leaving me with a measly 10 plants to harvest. Those 10 plants grew like wildfire, invaded the neighboring cucumber bed (which had succumbed to the blazing heatwave we were experiencing), and yielded more than 2 cups of dry beans during 14 rainless weeks — which was a wonderfully, soothing balm to my drought-riddled heart.

Acorns (Quercus spp.)

If you’ve been with us for a few years, you know that I’ve written lots about the potentials of returning to acorns as a serious subsistence food. Native nations from the east to west coasts utilized these abundant seeds, and the North California tribes like the Pomo and Miwok valued them particularly. You can check out earlier articles here and here.

The nice thing about acorns is that you don’t need to cultivate them — if you have mature oaks on your land, they’ll provide acorns on their own. And when your trees take a year or two off (they do this naturally), oaks are widely planted in parks, along city streets, and even near workplaces. Nobody’s picking up the acorns that litter the ground every fall, so you’ll have more than you can possibly process on your own.

Acorns need to be processed before consumption to remove bitter tannins. You can do this with boiling water, cold water, or a lye solution in water — all three methods yield different end products for your cooking needs. I prefer the boiling water method because it makes the best use of the free heat atop my woodstove and yields a nice, dark brown, fragrant “flour” for baking and porridge-making.

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.)

Amaranth is often sold as a garden flower. You’ll see a drooping species of it sold as “Love Lies Bleeding.” Its decorative nature often overshadows its true edibility, however. Once the staple grain of the Mayan and Aztec civilizations, amaranth is just as relevant in the 21st century if you give it a chance. Its tiny seeds can be ground into porridge, cooked whole like miniature quinoa, ground into a flour substitute, and even popped like popcorn.

A hot-weather plant, amaranth will flourish in the summer months, and since it matures relatively rapidly, gardeners with short growing seasons can still get the plant to seed-bearing maturity. It offers both edible leaves and versatile grain. And it’s another drought-tolerant plant, growing in areas that may not support more sensitive crops.

I plant amaranth in the early summer when I have some beds free after harvesting my garlic. It thrives in summer heat and matures so rapidly that I can harvest it well before frost.

Sunchokes (Helianthus tuberosus)

Its somewhat well known that indigenous gardeners domesticated sunflowers. What isn’t as well known is they actually domesticated more than one species of sunflower. In addition to cultivating Helianthus annuus for seeds or dye, ancient gardeners also tamed Helianthus tuberosus for its large, edible tubers. We have an earlier article on these wonderful vegetables here.

Now, you may have encountered a knobby, ginger-root-resembling thing in a health food store labeled “Jerusalem Artichoke” and thus, met one of the more poorly named vegetables in the world — as it is not an artichoke and not from Israel. These underappreciated tubers are the definition of easy food production. Simply plant them in the ground in the early spring, and wait. Come summer, they’ll grow to an impressive 8 plus feet in height in nearly all soil types, unaided, and will absolutely fill the ground with their edible roots. In fact, they’re so successful, you need to be careful where you plant them. They will take over, and there’s little chance of ever getting them out again.

Just make sure you harvest your sunchokes after a frost mellows them, otherwise you’ll find out why the are sometimes called “fartichokes.” Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

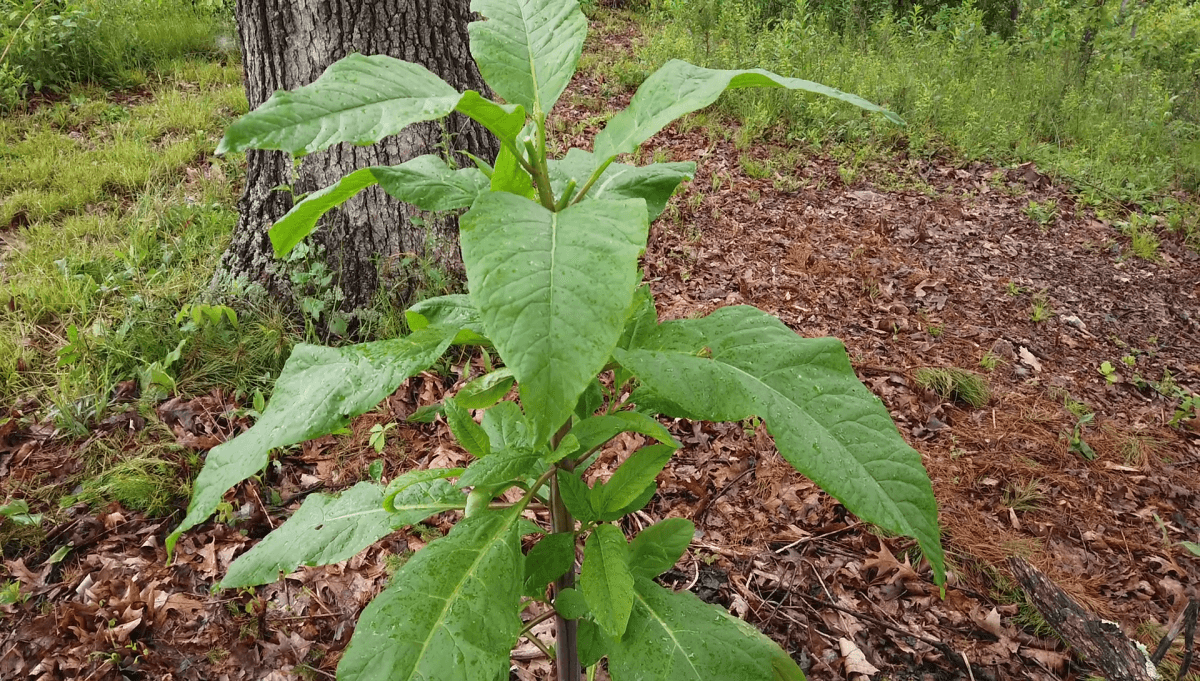

Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana)

Pokeweed gets its name from the Algonquin word “poughkone” which translates to “red dye.” The berries are the source of that distinction — and for those interested, we have an article on Insteading about how to transform the color-rich berries into a wonderful ink. But more wonderful than its ink is the food value of the spring shoots — something that can be gathered in massive quantities. We’ve waxed lyrical about the history and edibility of pokeweed in this earlier article for those looking to learn the ins and outs of this very underutilized food source.

While you may want to plant it in your garden, you do not need to. As anyone who lives in the range of this huge plant knows, its weedy nature means that planting and caring for it is redundant. It’ll grow in the strangest and least hospitable of places. This perennial plant will produce an amazing abundance of food in less-than-ideal circumstances.

American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea)

The American Lotus has recently come under fire in some states as an invasive weed, which I see as a huge opportunity. There are few plants that offer the abundance and diversity of food of these big-blooming beauties. If folks want to lower their numbers, there’s no better way to manage the population than by eating them.

The deliciousness of lotus is not a new discovery. They have offered tasty nutrition for thousands of years, and were cultivated in some ponds for easy access. Indigenous Americans would use their feet to uproot the large underwater tubers that were baked like sweet potatoes, and they enjoyed the immature, unrolled leaves and sweet seeds both immature and mature. Few wild plants are so abundantly generous.

Thíŋpsiŋla/Prairie Turnip (Pediomelum esculentum)

Some plants are just special, and you can often tell which ones are the most esteemed by the number of names they have gathered through time. Pediomelum esculentum has been called thíŋpsiŋla, timpsula, tinspila, prairie turnip, Indian breadroot, white apple, Psoralea esculenta (its former scientific name), and “pomme blanche.” Its importance as a food plant cannot be overstated.

These prairie plants produce a tasty, dry-able, long-storable root that is starchy and nutritious. The Lakota gathered (and gather) them in large quantities and wound them into long braids of winter sustenance.

Now, unlike many of the other plants on this list, prairie turnips aren’t easy to find. They’ve disappeared from much of their native range due to overgrazing and monocropping. If you want to reintroduce them to your own land, and have the patience to let them grow, you can harvest some of these beautiful and nutritious plants for yourself. My own prairie turnips are mere sprouts at the moment, so with my experience currently lacking, I’ll direct you to this beautiful article on foraging and cooking them.

This brief list still doesn’t cover the huge range of wonderful food plants from the Americas. I haven’t even mentioned mesquite beans or wild rice, but I hope this article has whet your appetite for more perennial and native plants that may someday grace your gardens, dinner tables, and who knows? Maybe become staple foods in other parts of the United States. Chime in below if there are other Native American plants that you grow (or want to grow).

I grow sunchockes and use them raw in salads, or cooked in a stir-fry.