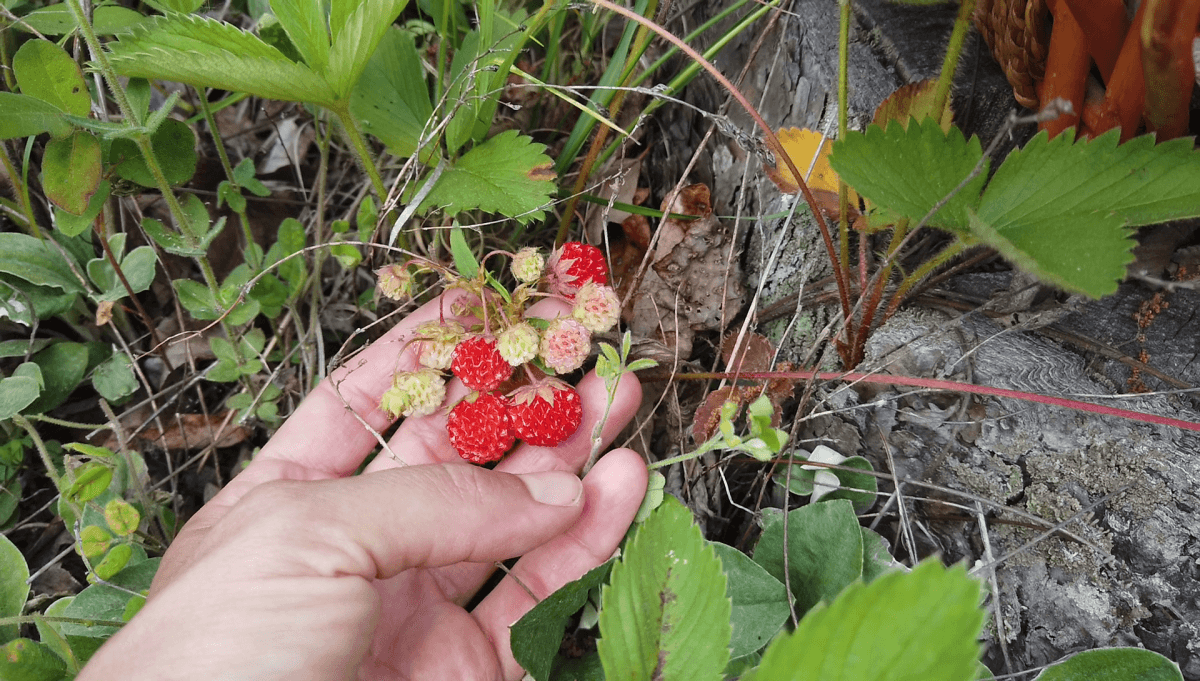

One of my earliest foraging memories is crouching in my childhood backyard. I nudged the leaves of a low-growing plant aside with a tiny, slightly grubby finger — and the white flowers that were there a week ago had changed into dimpled green spheres. I asked my mom, and she said they were strawberries. But these were nothing like the giant, hollow, triangular things I’d seen in the grocery store. I watched them carefully as they transformed from green to white, to a jewel-like red. They were no bigger than my smallest marble. How could these be strawberries? And they were growing outside in the lawn, of all places. My young mind thought strawberries came from the store.

Watch the video:

I never did get to find out what those strange berries tasted like. As soon as they turned red, they vanished. The chipmunks knew what I did not — when you find a ripe strawberry, you grab it before someone else does. What I did taste, however, was a new revelation. The thought of food coming directly from the ground under my feet (food that we hadn’t planted or bought) planted a seed in my mind. I didn’t understand what it meant yet, but it fascinated me.

The tiny mental seed planted by the first wild strawberry slowly and surely grew into a lifelong journey of enjoying and celebrating the free food that bursts from every nook and cranny of the wild places — if you know where to look. And now when I find wild strawberries, I give the chipmunks a run for their money.

Finding and Identifying Wild Strawberries

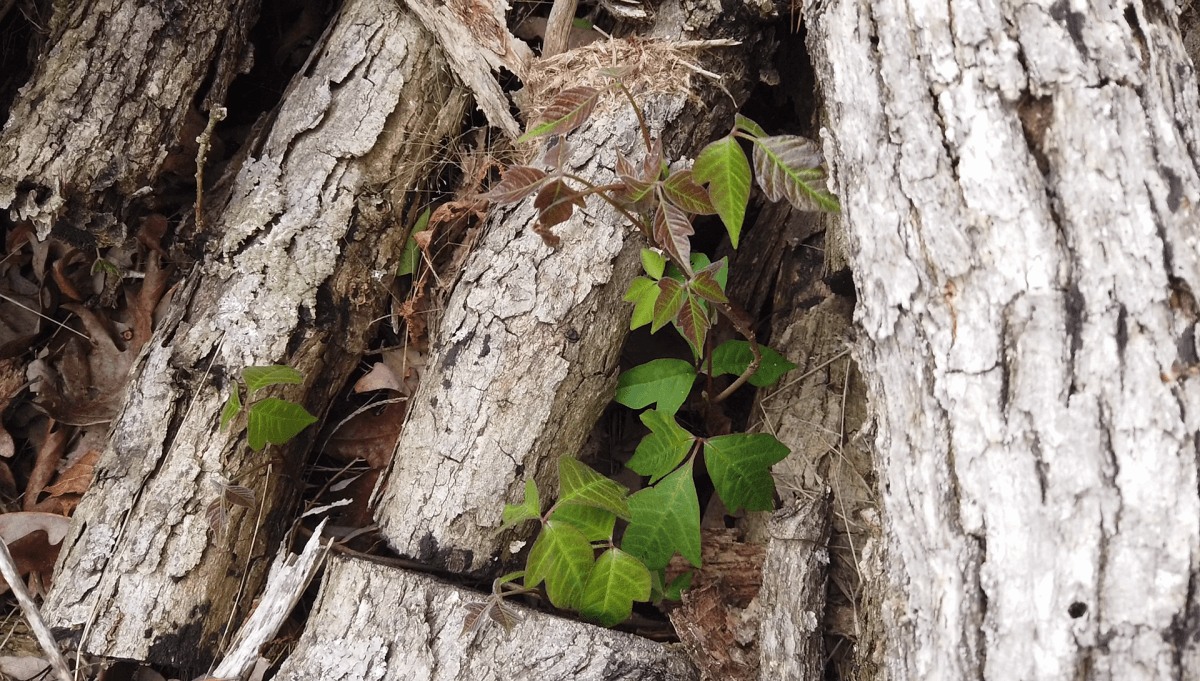

Once upon a time, some well-meaning person coined the phrase “leaves of three, let it be” as an attempt to prevent children from playing with poison ivy. It’s one of those axioms that sounds helpful but in reality, is pretty much useless to the forager. There are lots of plants with 3-parted leaves, and many of them are very useful. I’m sure people have backed away in fear from the low-lying leaflets of wild strawberry, or even drowned the poor, undeserving things in Roundup as an attempt to protect themselves. Let’s be smarter than that.

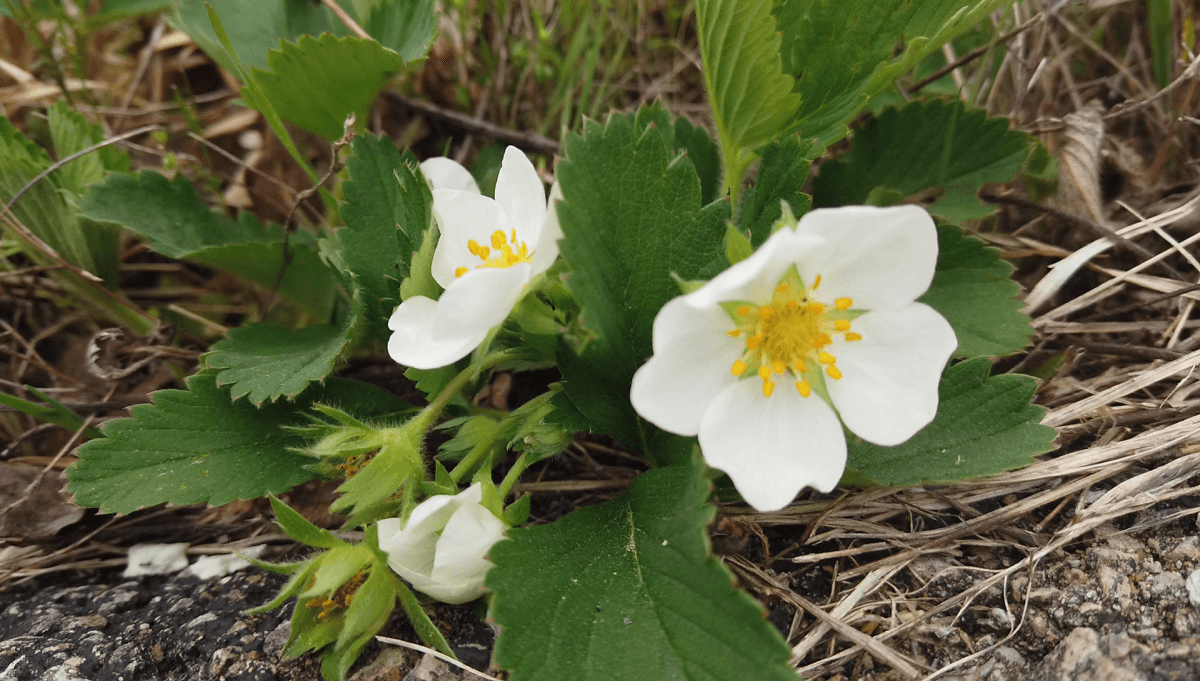

Wild strawberries grow much like their domesticated counterpart. It’s a low-growing plant that spreads by runners, often carpeting a suitable are of ground in dense, yet never overgrown colonies. They always seem to leave room for other plants to share their space. Its leaves are borne aloft on hairy petioles, and are usually coated with a layer of fine down on their undersides. These leaves are made of three leaflets that are the same size and shape–something that distinguishes them from poison ivy–and the edges of the leaflets are toothed. Though the fruit and flowers are truly seasonal, the persistent leaves are basically evergreen, offering a glimpse of green in the worst of winter.

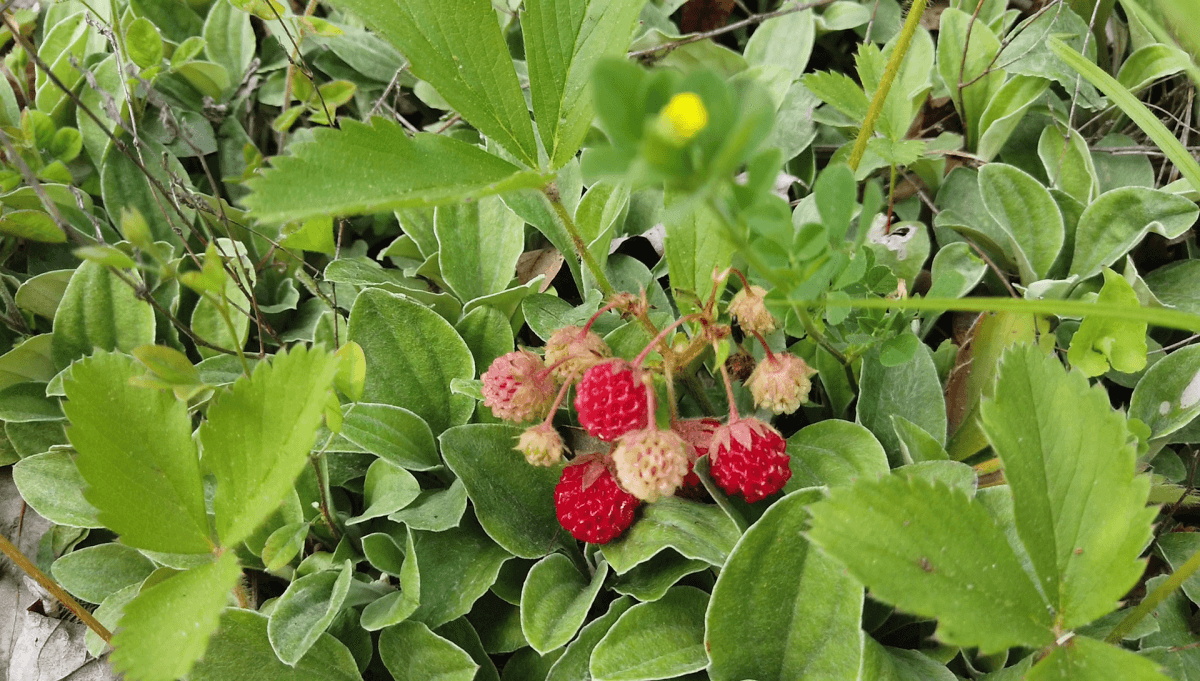

The blooms arrive mid-spring and are incredibly delicate, white, 5-petaled flowers. Locating a strawberry patch in bloom is an excellent way to scope out your future berry forays. As soon as the flowers are fertilized, the petals fall to the ground like they are sorry they existed in the first place. In their place, stalks of green embryonic berries develop. They’ll shift from green to white to red, and then, hopefully, you’ll be out there picking them!

There are several species of wild strawberry to be found in the United States, and they can all be used as you would any strawberry. The strawberry featured in this video/article is Fragaria virginiana, the common wild strawberry. Its fruits are small and intensely flavored with seeds resting in tiny dimples across the usually round surface.

Another wild strawberry you may encounter is the slightly larger woodland strawberry, Fragaria vesca. It has more elongated fruits, and the seeds rest on a flatter surface, rather than settling in dimples like the common strawberry.

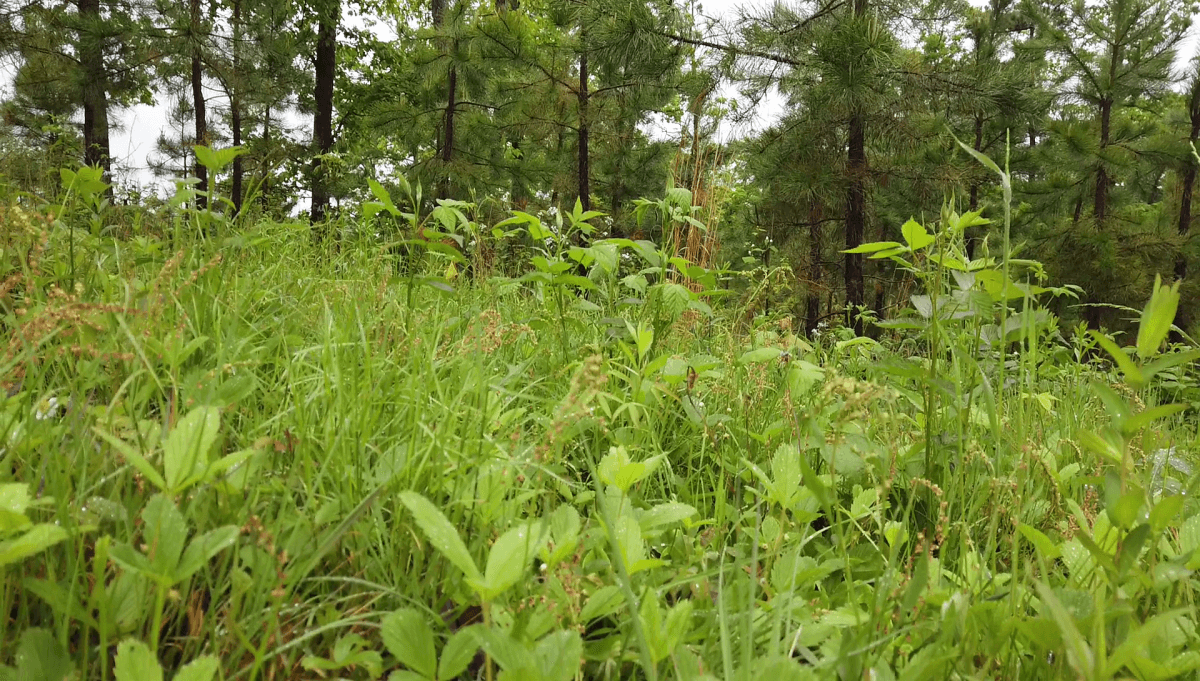

Both the common wild and woodland strawberry are found in much of North America, thriving in most sunny locations aside from the Deep South and desert areas. I have found that ideal wild strawberry habitats are usually areas at the edges of forests — places with ample light during part of the day, but also some shade and not too much standing moisture. The best strawberry patch on my land grows on a slope in the dappled area on the ground of our just-established timber lots. There, since the sun isn’t quite so direct as it passes through the young trees, the strawberries grow bigger and have longer stalks holding them clean from the ground. And the ducks haven’t found them yet. PLEASE don’t tell them.

Lookalikes

There are several plants — particularly those also in the rose family — that bear leaves that may be confused with a wild strawberry’s. They include (but aren’t limited) to the cinquefoils in the Potentilla genus and low-growing brambles in the Rubus genus, but none of them produce a strawberry-like fruit. The only risk you run with them is missing out on the real strawberries while you wait for them to produce red berries they’re never going to produce.

The plant that may really mess with you is Duchesnea indica — otherwise called the mock strawberry or false strawberry.

This plant produces a very strawberry-looking plant, though the leaves are smaller, less hairy, and just don’t look quite right if you’re expecting true wild strawberry. It notably has yellow flowers while wild strawberries bear white flowers. Nonetheless, it’s the sort of plant you can mentally force to be a wild strawberry if you don’t know the real plant instinctively. The shenanigans continue, however when it produces a small, bright red, seed-covered fruit that very much looks like it should be a delicious strawberry. The seeds sit on the surface like the pins on a pin cushion, rather than settled into dimples, and the fruit is suspiciously held above the leaves rather than hidden beneath them, but the hopeful novice forager may be too busy collecting them in glee to notice. And then comes the punchline: The taste … or rather, the lack thereof. These berries, while totally edible and non-toxic, taste like absolutely nothing. Or rather, they taste like disappointment, perhaps, and may be the reason many people who have been likewise duped write off the real wild strawberries as a waste of time.

Harvesting Wild Strawberries

One of the biggest aids in harvesting wild strawberries may surprise you. It’s a flower. Oxeye daisy is a wonderful plant in its own right. Its young leaves are edible, the blossoms make a healing poultice for bruises, and it grows freely. But it also happens to bloom at the exact same time that wild strawberries ripen. If you have a stand of these sunny white flowers, watch them in the spring, and as soon as a few start to open, grab your basket and get out to your berry patch. In my area, this happens around the last week of May, but it may be as late as mid-June depending on where you live.

Though ripe berries are bright red, they are typically hidden beneath their leaves. You’ll have to creep along the ground, brushing the foliage apart to find clusters of the fruit. Generously, the berries are held off the ground by a helpful little stalk, so even though they are a low-growing plant, they’re typically perfectly clean to pick.

If you are so blessed to find a loaded patch of berries, bring a big bowl with you to harvest. Though you may never get enough berries to fill it, a large bowl will allow you to harvest a lot of the delicate things without them crushing under their own weight.

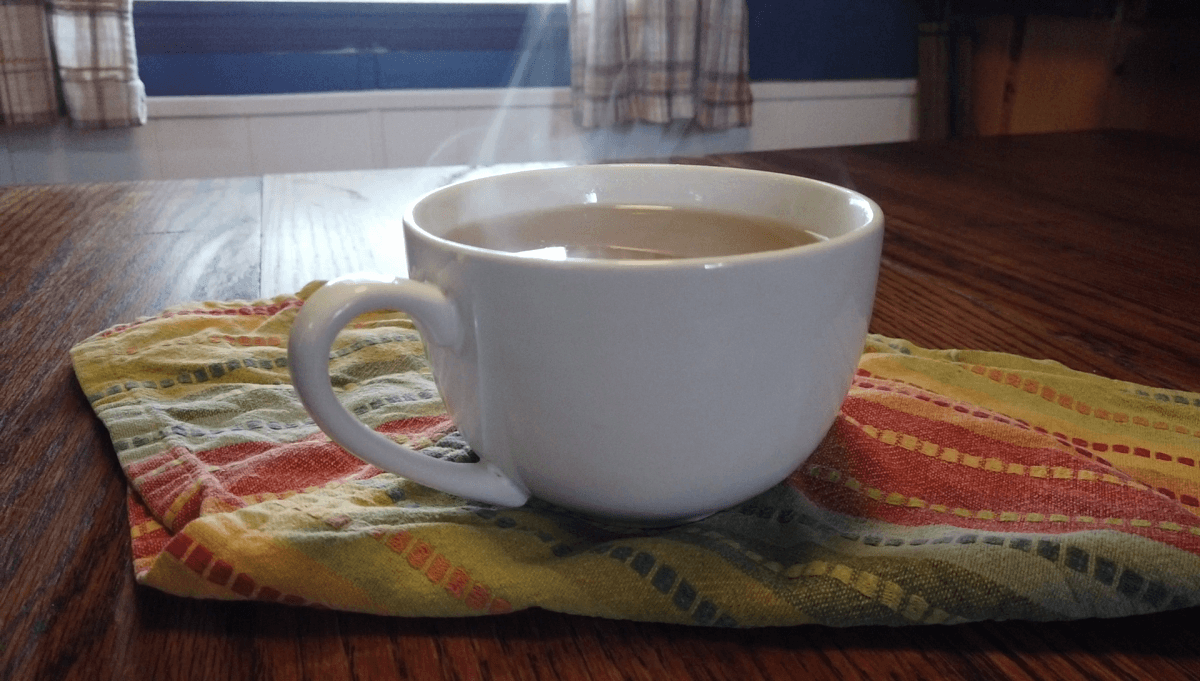

A second, less popular product to be found from wild strawberries are their leaves. They make a gentle and pleasant tea that basically tastes like strawberries translated through a leaf. It’s a golden color, and would be nice either hot or iced.

If you can identify wild strawberries in the early spring, the tender, new-growing leaves are best. But if you can’t locate wild strawberry leaves without the aid of the distinctive fruit, only harvest leaves at the same time you’re harvesting the berries. They can be used both fresh or dried, and I particularly enjoy a steaming cup of strawberry leaf tea in the dead of winter. The fragrant steam smells like late spring embodied, reminding me the cold won’t last forever.

Using and Storing Wild Strawberries

Most wild strawberries, I imagine, are immediately enjoyed out in the field where they grow, sparking on the tongue with their perfect balance of sweet and tart. But if you do find that elusive patch of berries that gives you the opportunity to make an actual harvest, you can do the exact same things with them that you would their store-bought counterparts. The only difference with wild strawberries is that you need to use them immediately (and that the taste 100 times better than storebought).

Wild strawberries are the definition of ephemeral delight. A cupful of berries picked fresh in the early summer sun are already a bit overripe by the time you get them into your kitchen an hour later. And if you ever make the mistake of putting a bowl of fresh picked berries on the counter or in the refrigerator with plans to get to them later, you run the very real risk of coming back to a pile of mold-fuzzy despair.

Either plan on eating or processing wild strawberries as soon as possible. I typically freeze the bulk of what I pick within an hour of bringing them home. As long as you picked it cleanly, there’s no need to wash the berries. Merely pinch off their greenish calyx and freeze them in jars. I use half-pint canning jars, and they work great to portion them out.

Wild strawberries also make amazing preserves or fruit leather if you have enough to make it. And for the ultimate in summer-on-a-plate, use wild strawberries with your best strawberry shortcake recipe. You’ll have a hard time going back to the store-bought berries after that.

Some people measure their riches in expensive cars, nice vacation homes, or luxury clothing. But that’s only stuff that you can buy with money. When I stand in my secret berry patch with a handful of strawberries, or when I look at a freezer full of wild berries tucked away, awaiting the blustery winter day when I bring them out to give us a breath of spring hope, I feel blessed beyond measure, and rich in something that no dollar could buy.

A beautiful description of the pure bliss that foraging berries brings! Up in the mountains in the western us, wild strawberries come on in august, not spring, so I am planning a trip asap! It truly is one of the most exhilarating hobbies – my young adult son just introduced his best friend to it & they have had a blast! Nothing else makes me feel such joy and connection with the world & the local ecology

Photo/Attachment:

I live in VT and discovered wild strawberries today on our property. I think I was a little late to the party as many were already gone or partially eaten, but I’ll be ready next year!

Photo/Attachment:

Right you are. Nothing beats harvesting from nature, and picking wild strawberries is certainly near or at the top of the list. We’ve been picking from a beautiful mountain top nearby with enough more than enough berries for a couple bus loads of friends and children who have gone out there too to pick. (I will try to attach a couple of pictures. If it doesn’t work I would be happy to email them to you.)

I have wondered about washing the berries because certainly there’s wildlife that does its things somewhere on the strawberry patch, but the these berries certainly don’t stand up very well to washing. It seems to take the color, life and juices out of them. I tend to agree with your comment about not washing the berries, but would like to hear more thoughts on that…