There are some flavorings that don’t seem to bear any resemblance to their natural counterparts.

Artificial cherry sodas resemble cough syrup more than a juicy, tree-ripened fruit, freakishly purple grape drinks hardly bring to mind anything that ever came from nature, and don’t get me started on banana-flavored candy. I have a special loathing for that nasty, fake yellow, weirdly chemical taste.

But of all the confectionery concoctions to be found, there’s one candy flavor that actually tastes almost exactly like the plant that inspired it — mint.

The first time I ever foraged for wild mint, I was shocked by how familiar the scent and taste were. It was, admittedly, a strange experience to be in the middle of a glade, nary a sign of civilization in sight, and suddenly stumble into a cloud of peppermint candy stick and mouthwash. At first, it was a jarring mental jolt back to the city where the memory had its roots. But as I knelt and wondered over the pungent, petite leaves of some American pennyroyal, I realized it was exactly the opposite.

I was awash in olfactory wonder of wild plants growing under unblemished, blue country skies. There was something beautiful about it.

Finding and Identifying Wild Mint

I should preface that I am using the word “mint” quite broadly in this article — maybe too broadly for a botanist’s liking, but just right for a forager bent on gathering aromatic herbs. When I use the word, I’ll be discussing a surprisingly large group of plants gathered under the Lamiaceae family instead of a single species.

Most of these plants share a set of notable traits that distinguish them as a part of that mint family. In fact, this combination of features is a good way to get a shaky identification of a plant in the field, though they will not give you a surefire identification that you should trust alone.

- They have a squared stalk.

- They have simple, opposite leaves.

- There is an aromatic smell, particularly when a leaf is crushed.

Anyone who grows their own herbs will immediately recognize that series of identifiers. The mint family is far larger than you may realize. Many of our beloved culinary herbs such as oregano, lemon balm, thyme, rosemary, lavender, and marjoram are all under that huge Lamiaceae family umbrella.

Related Topic: The Many Varieties Of Mint

Mint and their kin are surprisingly ubiquitous. Of course, they’re cultivated in gardens, but since humans have valued these piquant, low-growing herbs for so long, they have become naturalized in many states. Sometimes, you can discover the traces of an old homestead by finding peppermint, spearmint, or lemon balm growing seemingly in the wild. In reality, they’re remnants of a garden long forgotten. Look around the area, you’ll likely discover some sign of previous habitation close by.

Identifying 3 Types of Wild Mint

Now, this article will feature three types of wild mint that can be found in the Ozarks, but there are plenty more that may be local to you. So as we explore the following few species, keep in mind this is a very incomplete list. Hopefully, that’s an exciting fact for you. You’ll have to get out there and discover which are in your own location, just waiting to be discovered and enjoyed.

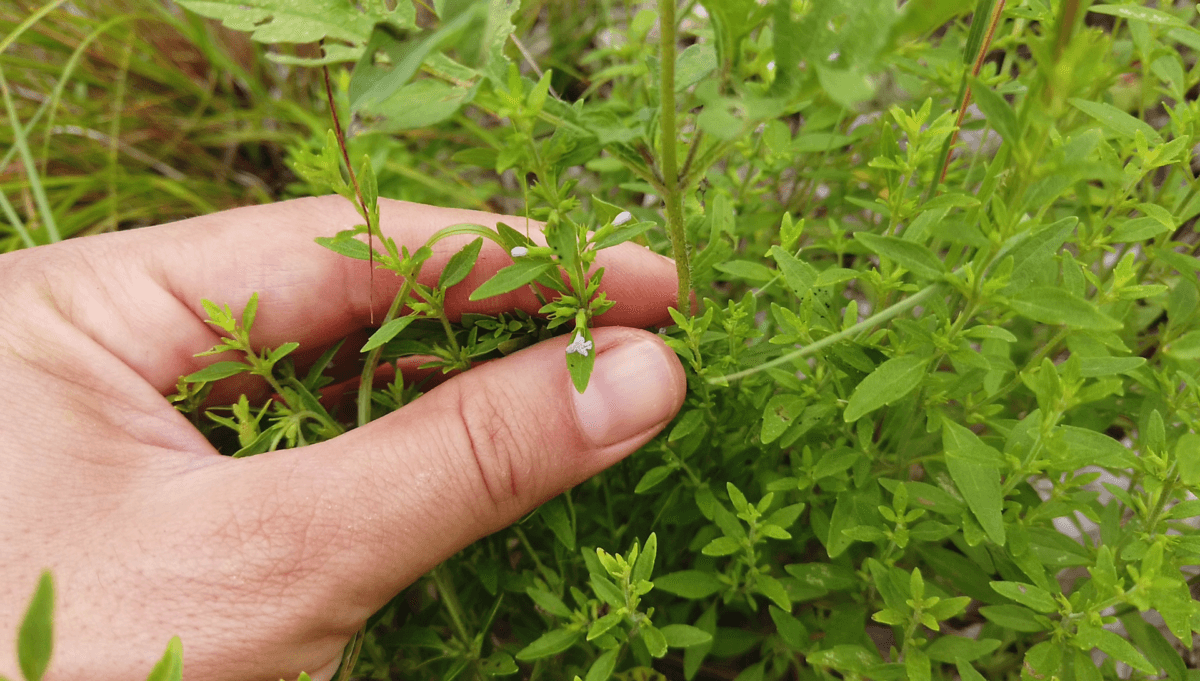

American Pennyroyal (Hedeoma pulegoides)

This is an unusual member in the mint family. American pennyroyal is an annual, rather than a perennial like the rest of them. It produces tiny leaves on woody branches that are rarely over a foot tall, and bears tiny, simple leaves and even tinier pale flowers. What this plant lacks in mass, however, it more than makes up for in aroma. It’s the mintiest mint I’ve ever laid nose on. As with all mint, it has distinctively squared stems and opposite leaves.

Pennyroyal can be found alongside other plants that favor dry grasslands such as black-eyed Susan, wild bergamot, and goldenrod. It often grows in areas colonized by oaks and hickories and among rocks and gravel. It is most active in late summer, perfuming the air to the chorus of cicada song.

Dabblers in herbal medicine might be turned off to this mint because of some warnings about toxicity (often listed in medicinal books). The issue concerns an aromatic oil called pulegone found in American pennyroyal (and others, for the record). Taken in the hyper-concentrated essential oil form, pulegone is toxic and has led to several poisonings when misguided folks took large doses of it.

No one should ever take a large dose of any essential oil. And pennyroyal found in the field isn’t an essential oil. Consuming the natural plant as a tea or seasoning will not give you anywhere close to the amount of pulgone that could cause an issue, and there are no records of anyone being poisoned from normal consumption. The cautions against this mint are moot for the forager, and only serve to demonize a perfectly good plant.

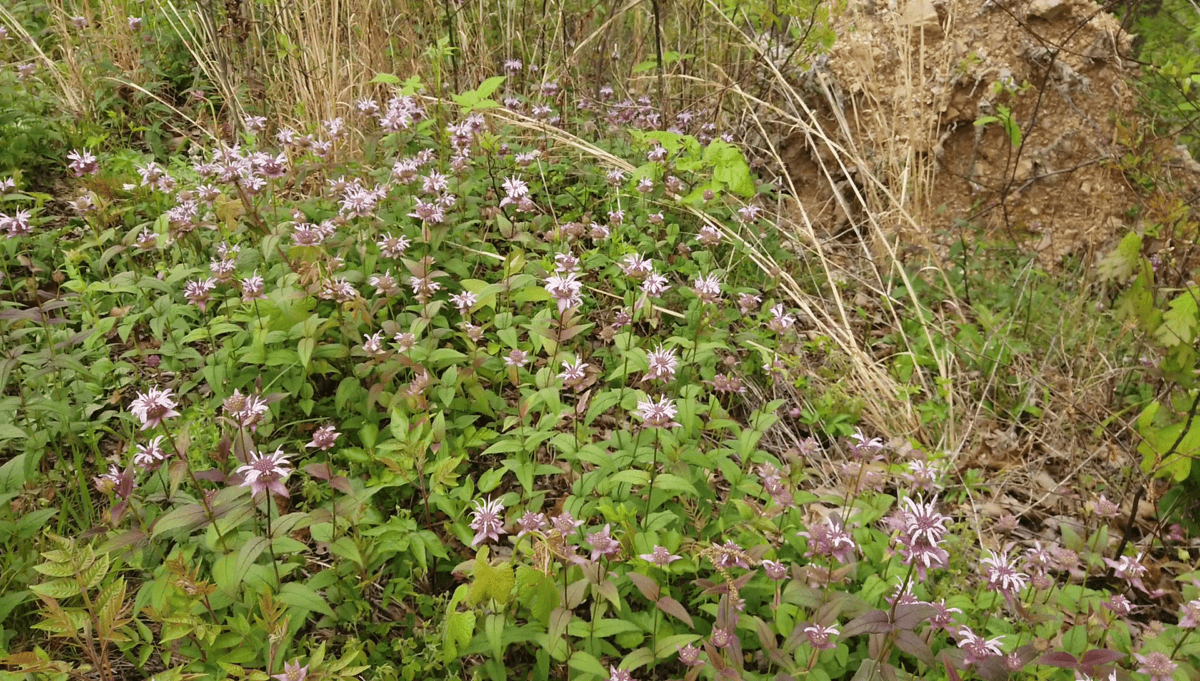

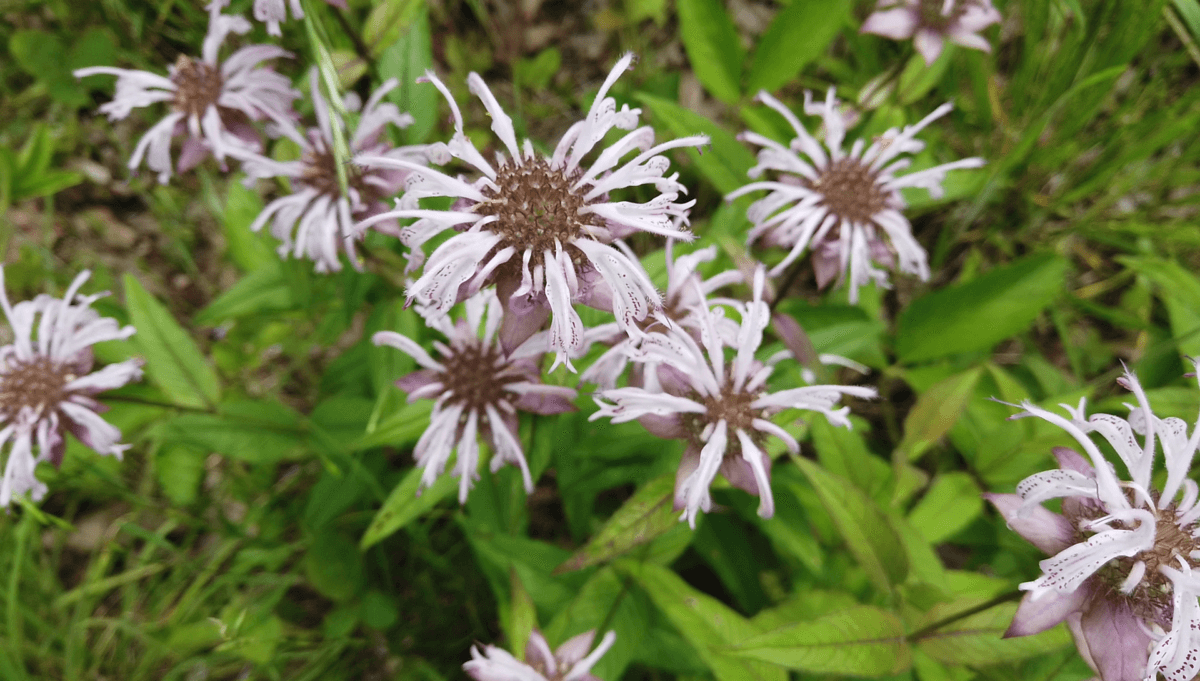

Wild Bergamot (Monarda bradburiana)

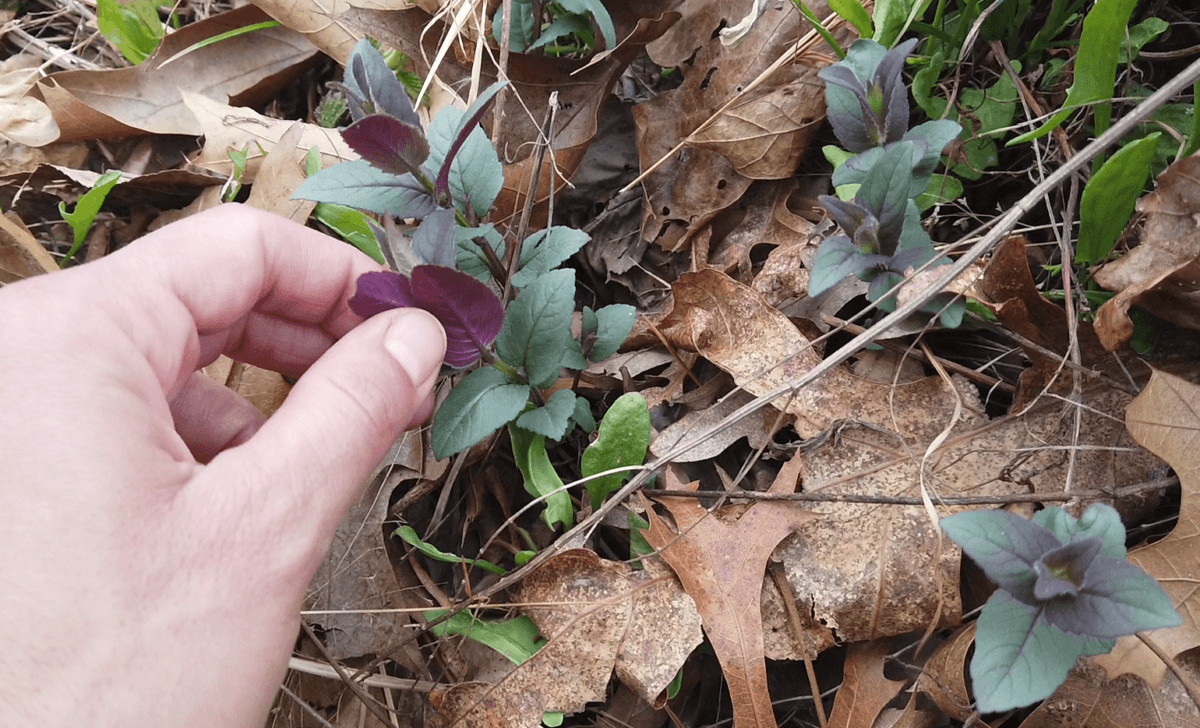

Sometimes called horsemint, this butterfly and bumblebee magnet of a wildflower is one of my favorite sights in spring. As with many wild, mint-family plants, you can find the new spring sprouts of this perennial growing up beneath the dried-out seed heads from last year. In the case of wild bergamot, these seed heads are round balls held about a foot or so off the ground.

Wild bergamot can typically be found in the same company as ox-eye daisy, black-eyed Susan, and Queen Anne’s lace. Sunny, open fields and glades are ideal places to hunt for these spring-blooming beauties. When they first emerge from the ground in April, the leaves are beautifully dark green on the top and surprisingly purple on the underside. Being mint, you know they’ve got squared stems and opposite leaves.

In late spring, they bear spotted white or pale lavender blossoms that grow in a ring like a ragged, big-centered daisy. Whenever the sun warms their leaves, the surrounding area is filled with their fragrance. True to the name, the smell and taste are somewhat reminiscent of Earl Grey tea.

If you can’t find wild bergamot, your land may be home to any of its close siblings, such as the pink-flowered, wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), common bee balm (Monarda didyma) or spotted bee balm (Monarda punctata). Their use is pretty much interchangeable among the Monarda genus, as they are all very agreeable.

Dittany (Cunila origanoides)

Also called wild oregano, dittany grows in round, wiry shrubs that colonize dry, acid slopes. You’ll often find it on the borders of forests or the shaded areas of trodden paths. As with the Monarda genus, you can find the new shoots of this perennial beneath the seed heads from the previous years. It grows once spring really takes hold, becoming lush and green around May. The finely-toothed leaves are a glossy dark green when mature, and grow opposite each other on squared stems. The delicate, delightfully purple blossoms emerge in full force in September.

The heady aroma of a woodland slope colonized with bunches of dittany, is one of the private delights of the forager who knows to look for it. Serenaded by wood thrushes and warmed by the early fall sun, there are few locations more pleasant.

In my area, dittany is famous for being a source of “frost flowers” in the fall. Around the first hard frost, water gets squeezed out of cracks in the stem and instantly freezes, forming delicately bizarre arcs of ribbon-like ice.

Now, that’s just a sampling of the mint-related herbs that are to be found out there, but probably a long enough list to start. In your own area, you may find plenty of wonderful wild mint, including beefsteak plant (Perilla frutescens), slender mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium), water mint (Mentha aquatica), and wild mint (Mentha arvensis). Mint can be found everywhere, and their ubiquity is a delight for foragers the country over.

Harvesting Wild Mint

Aromatic plants like these are at their peak in the morning after the dew has dried from their leaves. When harvesting, you don’t have to just pluck leaves either — the whole plant is aromatic and useful from the flowers, to the leaves, to the stems.

That said, they are all pollinator magnets, so if you cut down the whole plant, you’ll be removing an excellent source of nectar from them. I heartily recommend harvesting only one-third of any given stand, allowing the plants to finish their life cycles, make seeds, and feed the other creatures that share your land. And frankly, the sight of the flowers can be food for the soul when you don’t take it all for your stomach.

You can use mint fresh, of course, but the season for fresh herbs is brief. To preserve, arrange them in a single layer in a dry, airy place as soon as you can. A covered porch, a solar dehydrator, or an airy hallway are all great locations.

You’ll know they’re completely dry when the leaves crisply fracture apart when crunched. If desired, you can strip the leaves from the stems and store them separately, or you can snip the stems into short segments so they don’t get in the way. You can then store your dried mint in mason jars for the winter like you would any other herb.

Cooking and Using Wild Mint

Strong-flavored and pungent, they’re best used like any other herb — sparingly as a flavoring. That said, both dittany and wild bergamot leaves can be used in place of oregano on a pizza or in pasta. They are a very pleasant tea as well. Hot or iced preparations will give you slightly different flavors, so make it any way you want.

The potent smell of pennyroyal may be pleasant to us but is a turn-off to annoying pests like mosquitoes and ticks. When I pass the many patches of pennyroyal by my barn, I brush my hand along the tops of the herbs, and spread the aromatic oil all over my arms and neck.

Pennyroyal retains its aroma and flavor wonderfully when dried, making one of my favorite teas to brew and sip with a bit of honey.

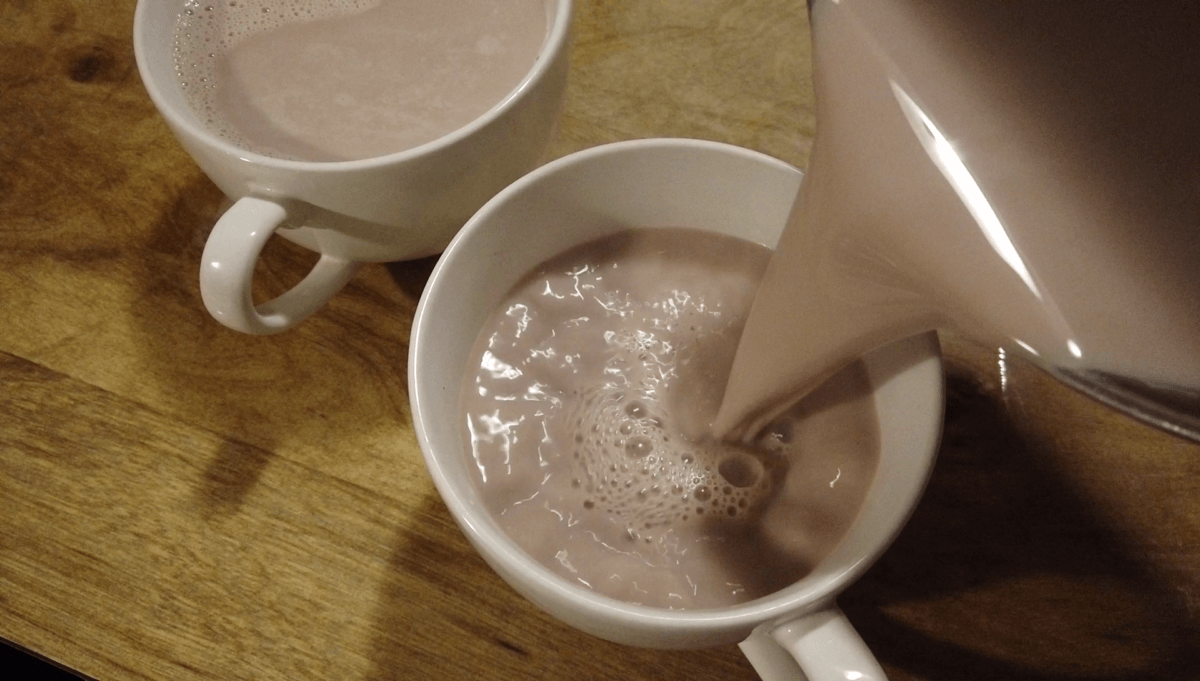

But for an extra-special treat midwinter, place a tablespoon of pennyroyal leaves and stems in half a cup of water and bring to a boil. Turn off the heat and allow to steep for five minutes. Then, after straining out the leaves, mix two teaspoons of sugar, two teaspoons of cocoa powder, a dash of salt, half a teaspoon of vanilla, and a cup and a half of milk into the pot. Warm it to drinking temperature, and you have an absolutely decadent mint hot chocolate to sip as you warm your toes by the woodstove.

With an easy-to-identify nature, their persistence through spring, summer, and fall, their unmistakable smell, and pleasant range of flavors, mint may be some of the more beginner-friendly plants to forage. I wish more people knew the wild mint varieties, and rather than saying these wild plants remind them of chewing gum or toothpaste, they consider that chewing gum and toothpaste make them remember the real plants, growing in their wild, uninhibited sprawl outdoors.

Keep your eyes open and your nose to the breeze. Come springtime, mint will be inviting you back to the fields and forests.

Leave a Reply