This is an open letter to the brambleberries of the world, particularly those blackberries growing along the edge of my ravine.

Dearest Brambleberries:

It is with great perplexity that I write to you. There is an understanding between berrykind and humankind that has endured for thousands of years. You produce delicious, sweet fruit. We eat it. We get tasty nutrition. You get your seeds and genetics spread far and wide beyond the reach of your earthbound branches. The strawberries understand this beautiful system. The blueberries get it. Heck, even the cherries are in line. But you … you and your ilk haven’t gotten the memo. For some reason, photosynthesizing plant though you be, you want blood. You dangle clusters of the most luscious summer fruit within reach, then you stud your branches with death spikes that are totally unmerited. As soon as a shirt sleeve is caught in your vines, you grab a handful of hair, wrap around an ankle like barbed wire, and knock my hat from my head. This is an act of aggression that is totally inappropriate given the nature of our potentially beneficial relationship. Why taunt me with juicy abundance, then scratch and rip and mangle when I attempt to accept your invitation?

Sincerely and Scratchedly Yours, Wren

Watch The Video

Now obviously, there’s no bush in any ravine that can read my letter, but there are plenty of you out there who, likewise, may have a complicated relationship with this thorny, widely-growing shrub. Whether you find yourself at odds with brambleberry’s thorns or annoyed by the way it takes over any area you haven’t mowed, I think we can all agree these delicious summer berries are well worth the effort. And even though you may have not picked blackberries or raspberries from the forest edge since you were a kid, it’s high time to head back out to the sticks and get you a basket of finger-staining goodness.

Finding and Identifying Brambleberries

“Brambleberries” is a catch-all term for more than a hundred unique species of plants that bear their edible, easily recognizable fruit and grow on canes or creeping stems. Within that family, you’ll find salmonberries (Rubus spectabilis), cloudberries (Rubus chamaemorus), raspberries (actually a term for many in the Rubus genus), dewberries (a name for several ground-hugging species), thimbleberries (Rubus parviflorus), and many others that are abundant where you live.

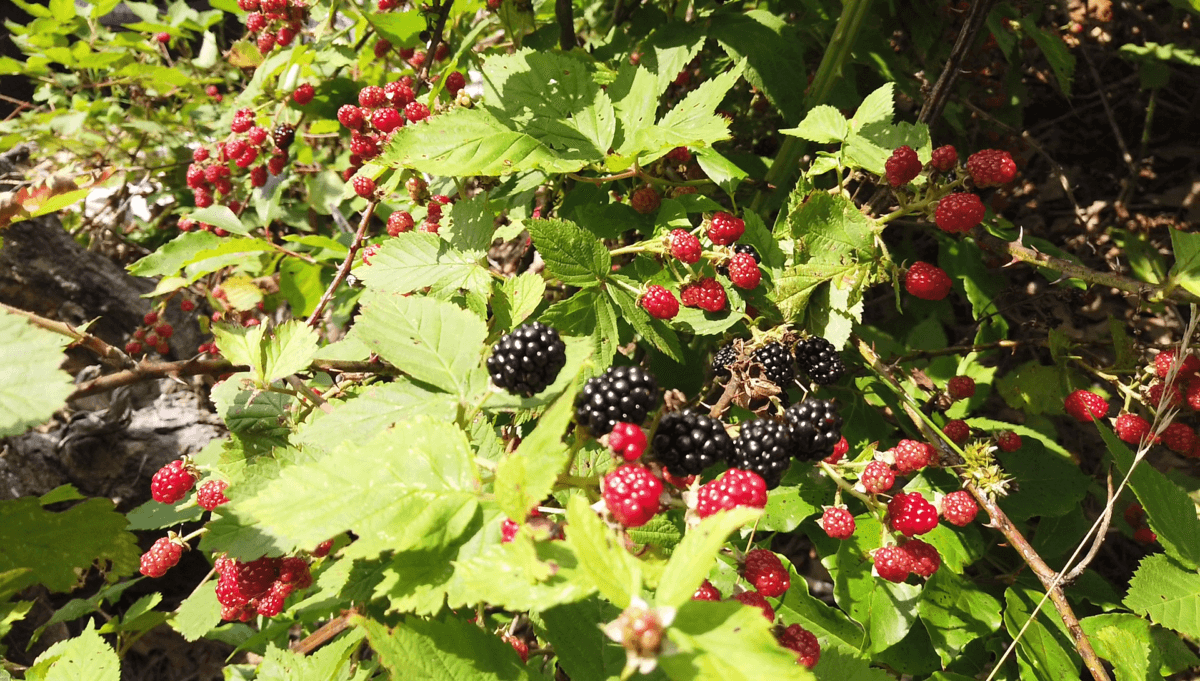

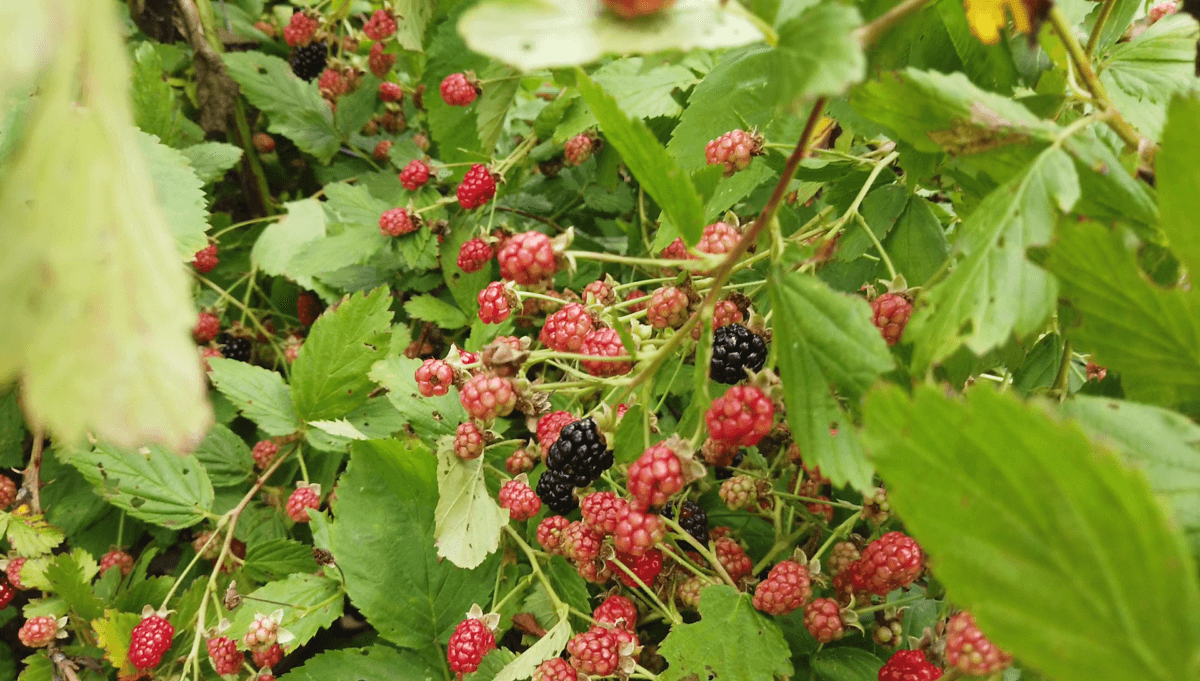

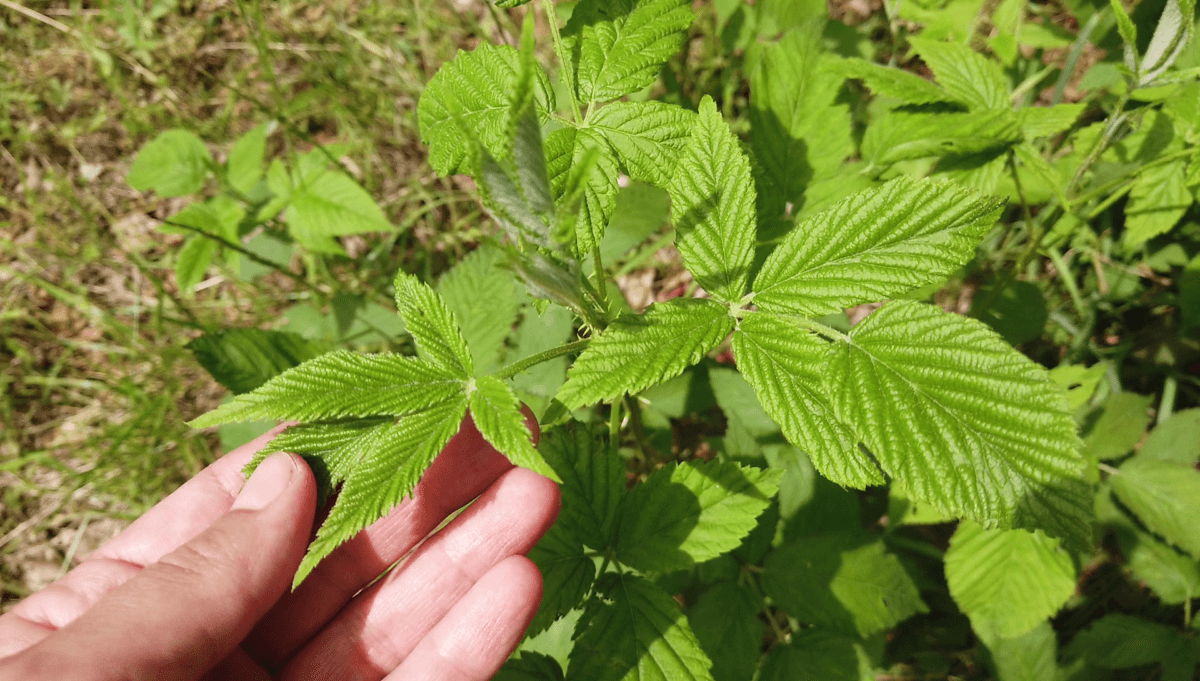

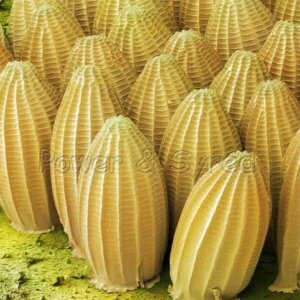

The easiest way to identify a brambleberry plant is by the berry itself. They are distinct clusters of single-seeded fruits all pressed together. Sometimes they pop off the receptacle like a little cup (you see this with raspberries and the appropriately named thimbleberries). Other times, they pop off the stem with the receptacle contained (as with blackberries and dewberries). Their leaves are typically compound and made of three or five leaflets, though there are some exceptions. Most are spiked with thorns of varying intensity prickliness. All of them have 5-petaled flowers that look like wild roses. The plant form sometimes trails on the ground and other times, grows like a loose bush depending on the species, but rarely grows beyond 5 feet tall. Beyond that, individual species all have their idiosyncrasies.

For the purposes of this article, I’ll be featuring blackberries, as they’re the plant I have the most experience with, but all the tips and ideas apply to whatever brambleberries are most available to you.

Related Post: Foraging For Wild Berries

Bramblebery Look-Alikes

Though there are many different species of brambleberries, distinguishing them is not particularly important to the forager — if it looks like a brambleberry and bears fruit like a brambleberry, it’s edible. Some, of course, are tastier than others, but none are worth passing over, in my berry-loving opinion.

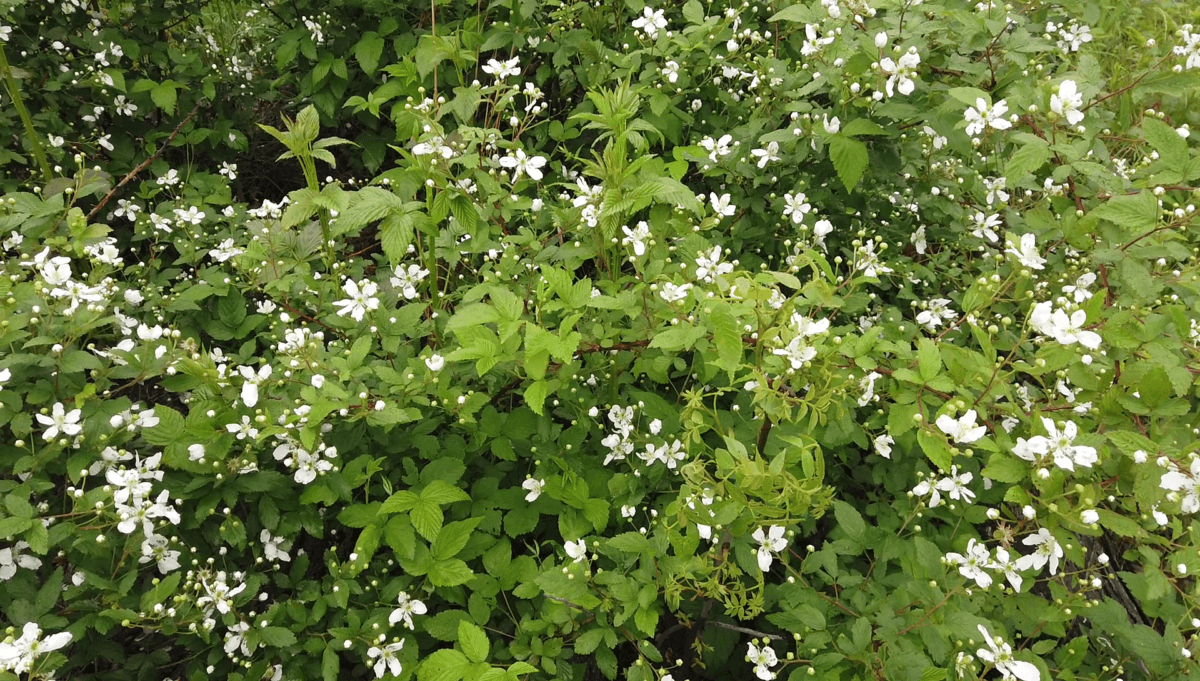

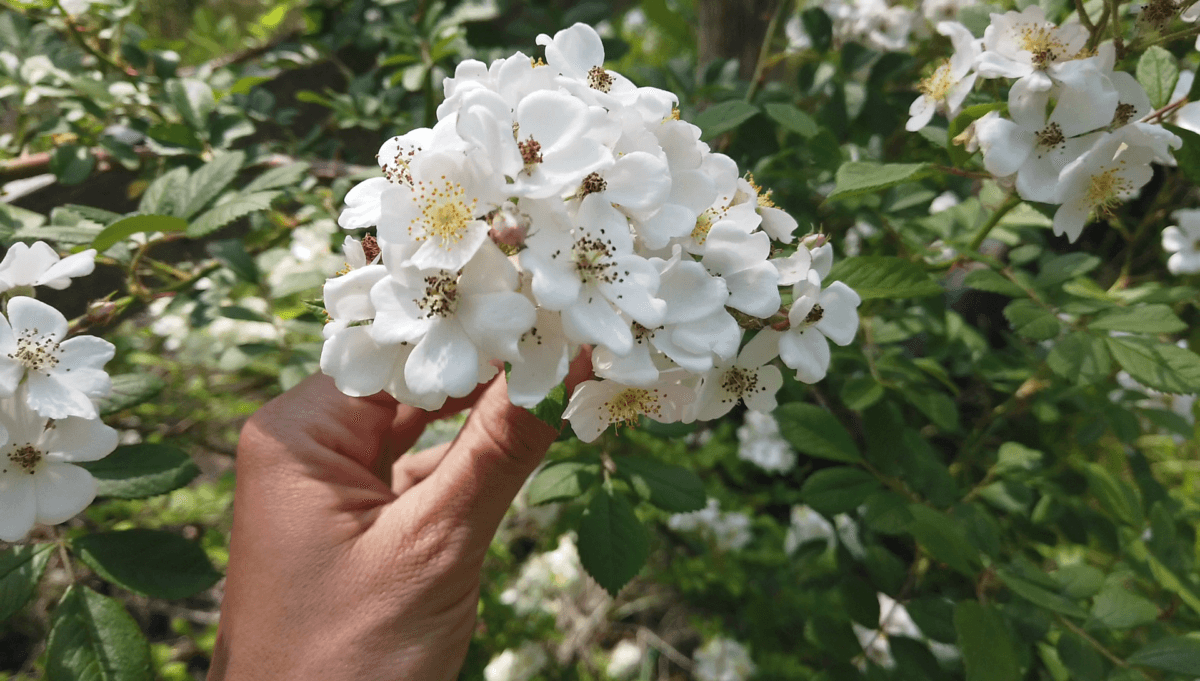

But there are some plants that might fool you into thinking they, too, are part of the brambleberry retinue. Probably one of the easiest for a new forager to mistake is the very brambleberry-like branches of the multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). This spiky, invasive bush is a cousin to the brambleberries (all of them are part of the rose family), and it also likes to tear pants and ankle skin like its relatives. Even their admittedly pretty, white flower clusters are visually similar to blackberries. The error for the forager is to wait on a multiflora rose bush to bear blackberries and miss out on the real fruits. Multiflora rose won’t bear its tiny, red rose hips until mid-fall.

Distinguishing blackberry from multiflora rose is easy if you take a minute, though. Look at their leaves. Multiflora rose leaves are distinctively 7-parted, and all connected by leafy tissue. Now, brambleberries may have different amounts of leaflets depending on the species, but they have clear petioles, and are typically larger in size as well.

The flowers are obviously different too, once you take a closer look. Though both flower clusters bloom at the same time, multiflora rose are held in a tight cluster, petals touching. Blackberry blossoms are not as crowded. All are lovely, though, and bees go nuts over them.

Greenhorn foragers may confuse other berries for blackberries, I suppose, but it’s a stretch. I’ve read of goldenseal berries being confused for brambleberries, but if you can’t tell the difference in plant forms between a big thorny bush and this endangered, palmate-leaved plant, you really shouldn’t be chewing on any wild berries until that’s straightened out. The most likely candidates for that confusion are small children. On that, I recommend teaching kids how to forage as soon as possible. Equip them with correct knowledge and guided experience, rather than cover-all warnings about scary poison berries, and you may be surprised how observant they can really be. All the same, I recommend you not let young children forage unaccompanied.

Harvesting Brambleberries

The biggest hurdle to harvesting many types of brambleberries is the inevitable physical trauma that accompanies a berry excursion. You’re probably going to bleed a little. For hard core berry pickers, those scrapes and scratches are a mark of pride, a rite of passage that means we entered the tangly trial and emerged with a basket of fruit in sweaty victory. Just remember to wear clothes that you don’t mind getting torn. I always have to patch some of my clothing by the end of summer.

An additional caution comes for those who forage in really wild places. Though it’s easy to get berry tunnel vision, look around as you battle those spiky branches. Birds love brambleberries, and some enterprising snakes have seen that as an opportunity. Every so often, you may find a snake quietly hanging out near loaded bramble bushes. This is no issue if you give it space. It’s not on the hunt for you — but nobody enjoys blundering into a snake.

Now, the nice thing about blackberries is that they are abundant, and they ripen many, many berries at the same time. If you have a big enough series of patches to visit, you can likely go out every other day and come back with the same generous haul. My blackberry season usually lasts a full month, and peaks around a week into July. I spend many afternoons furiously picking berries as fast as I can, knowing I’ll have long forgotten the bloodshed once I’m baking a winter berry pie.

Picking Blackberries the Right Way

Here’s a pro tip for those of you looking for the sweetest blackberries. Blackberries often darken when they are almost ripe, but they can still be quite sour despite their appearances. The sweetest, ripest berries are those that fall off the branch at a touch. If you really need to pull to get a berry off the branch, it’ll make your mouth pucker. But if it happily rolls into your hand, it’s going to be a good one.

Harvesting Blackberry Leaves

A secondary product a blackberry can offer you is leaves. The young spring leaves, still tender enough to pick without pricking you, are a tasty green that you can eat sauteed like spinach. Bright green leaves of any size and maturity can be picked and used fresh or dried as a surprisingly pleasant tea. I like to blend blackberry leaves with red clover blossoms and wild bergamot flowers and leaves, to make a perfect cup of spring-field tea that you can’t buy in a store for any price. Finally, for those interested in learning to harvest their own medicine, you should know that blackberry leaves brewed to a medicinal strength were traditionally used to treat bouts of diarrhea. I’ve seen it work, but you should do your research on such matters and draw your own conclusions.

Cooking and Enjoying Brambleberries

Perhaps the truest way to enjoy brambleberries is out in the field, sweating and tousled, and happy. I’ve never tasted a better berry than when I’ve earned it. But for those who find enough to bring back to the kitchen, the uses of these tasty fruits are legion. The biggest thing to remember, as with most all wild fruits, is to process them as soon as you can — the sooner the better. Ripe berries are entropy magnets. Leave them on the counter too long, or leave them in the fridge for more than a day or so, and you’ll only have fuzzy white mold and sadness as the result of all your efforts. If the mere idea of boiling canning jars in the summer has you sweating, remember you can freeze them in quantity during the harvest and process them at leisure in the fall and winter. Brambleberries freeze wonderfully and have no noticeable change in quality.

Now (I imagine) I don’t have to give you too many ideas on how to use brambleberries — they work the same as their grocery store counterparts. Blended with pectin-rich apple pulp, they make tasty fruit leather. Simmered and thickened with a touch of sugar, you’ll have a fabulous jam in record time. I can’t help but share two of my favorite uses, however.

Brambleberry Soda or Wine

The first is to ferment mashed berries into a delightfully effervescent, naturally-fermented summer soda/wine. I’ve got a whole article on that surprisingly easy process here on Insteading if you’re interested.

Brambleberry Summer Tart

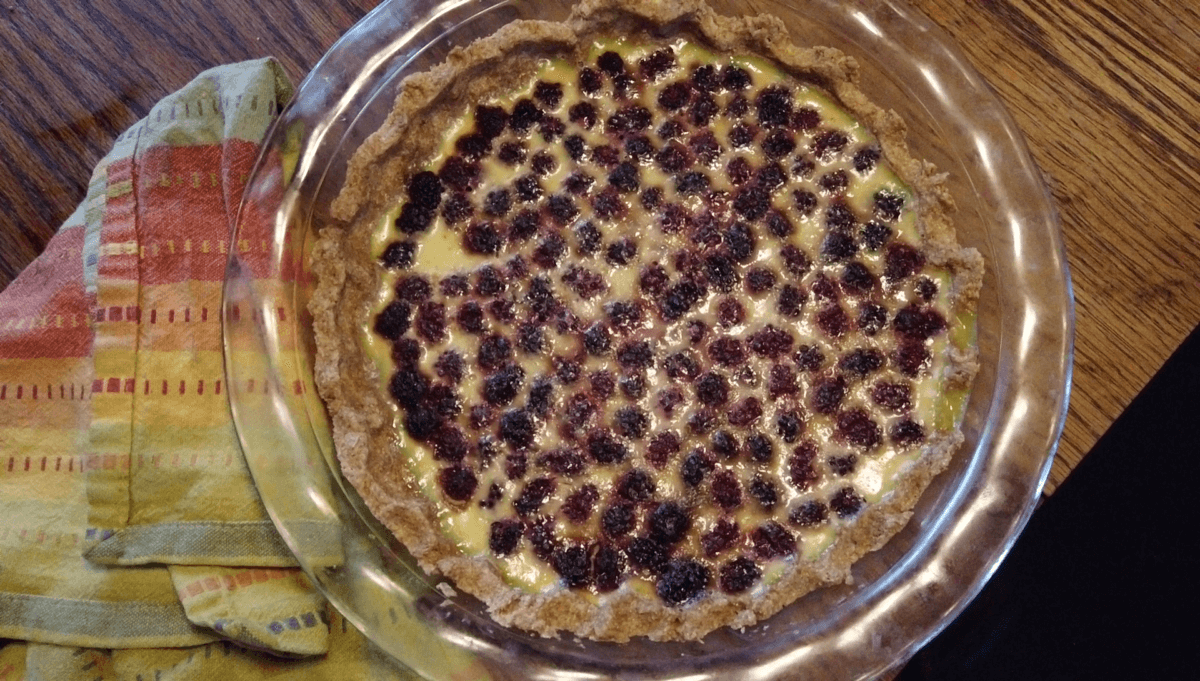

The second is to bake them into a slightly sweetened summer tart that tastes like sunshine on a plate, if you’ll forgive me for waxing poetic about a dessert. As with all my recipes, this is more an idea-share than a firm formula.

1. Prepare the Crust

Mix your favorite crust for a standard pie plate. My hectic-summer-day-no-fuss crust is made from 1 cup of whole wheat flour, 4 tablespoons of butter, a tablespoon of sugar, and a pinch of salt. Blend those ingredients with your hands until the flour has the texture of damp sand, then add water in tablespoon amounts until it all sticks together. Forget the rolling pin, just press the crust into place. If you’re cooking indoors, bake in an oven at 375 degrees Fahrenheit for 10 minutes or until set. I use a sun oven in the summer, so the crust goes in there for an undetermined amount of time while I get the filling ready.

2. Arrange the Layer of Berries

Once the crust is baked, arrange a layer of berries across the entire bottom. Then, in a bowl, mix together 2 tablespoons of sugar (or more if you need, but I’m not big on super-sweet things), a pinch of salt, two eggs, a tablespoon of flour, and about a one-half cup of milk. If you have a lemon, you can throw in the juice of it (and the zest as well) to add a burst of sunny flavor. If you have lots of time, you can also brown 2 to 3 tablespoons of butter, and add that to the batter for a rich, nutty background flavor.

3. Bake the Tart!

Get the filling carefully poured over the berries, then bake the tart in the oven at 375 degrees until it is cooked and the custard is set. I’m guessing this will take about 20 minutes in a conventional oven, but I bake this tart in my solar oven, and have no idea how long it would take (#weirdoffgridproblems)! Let cool, cut in slices, and enjoy while sitting in the shade of a covered porch.

Enjoy Your Foraging

So whether you’ve harvested a batch of berries and are trying to think of what to do with them, or haven’t plucked these tasty fruits since you were knee-high to a grasshopper, I hope your summer will be filled with luscious fruits and not too many scratches. On my homestead, as I’m sure must be true on many others, the never-ending encroachment of the wild blackberry bushes eventually get their just desserts. Though that razor-wire of brambly canes crowding our forest path may have sliced me all summer, once the berries have been picked and the last of their good, fresh growth has been plucked for tea, out come the pruners, wheelbarrows, and gloves. My goats are very happy to have the last laugh.

Leave a Reply