About five years ago commercial beekeepers across the US began reporting bee losses in record numbers – about 30% each year. This level of loss is unsustainable and many beekeepers are going out of business.

Aside from the economic issues, the record number of bees dying should be alarming everyone who eats. About one in every three bites of food consumed in America, come from foods that require pollination.

No only have the bees been dying in record numbers, but about the same time bees began to die in unusual ways. Beekeepers were going to a hive and find the queen, a few workers, good amounts of brood (baby bees), and plenty of honey – just no adult bees. So where had they gone and what was causing them to leave?

Researchers dubbed this phenomena Colony Collapse Disorder or CCD and it has been the source of much research and finger pointing ever since. Is CCD the cause of these record losses?

Before 2006, most of the time commercial beekeepers reported around 10% losses each year. That means that 10 out of every 100 beehives they managed died over the previous 12 months. Most of these losses were reported in the spring and were due to starvation. A hive that either doesn’t have enough bees to keep themselves warm enough to use their honey stores or a hive that doesn’t have enough honey stores will starve to death.

Most commercial beekeepers have to replace their lost colonies, costing them time and money. They purchase packages of bees each spring from beekeepers in the southern US.

Jeff Pettis, of the USDA Agricultural Research Service Bee Research Laboratory in Beltsville, Maryland says, “CCD is likely due to a number of factors, not just a single smoking gun.” Some of the potential factors include stress, pesticides, mites, and viruses.

Stress

Commercial beekeepers load up their hives and transport them all over the country. Many commercial beekeepers head to California in the early spring to pollinate the almond trees. While on route to California, the hives are closed up so the bees cannot leave. The hives are subjected to changes in temperature and fed sugar water. Once they are done pollinating the almonds, the bees are packed up again and sent to another state to pollinate another crop.

This kind of change in temperature and diet can cause stress on a colony. Unlike many mammals or even other insects, a colony of bees, rather than individual bees, has an immune system. If the colony is stressed then their immune system doesn’t function properly.

Pesticides

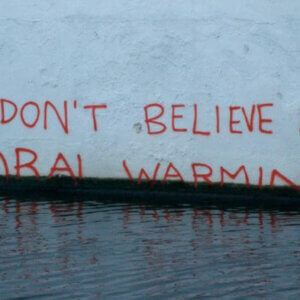

Pesticide use has increased over the last few years. In particular the use of neonicotinoids. These pesticides attack the central nervous system of insects and causes paralysis leading to death. This class of pesticides had been banned or limited in its use in other countries because of its effects on honeybees, but in the US its popularity is growing.

While some exposure to neonicotinoids might not outright kill honeybees, low level exposure can cause honeybees not to be able to navigate properly and may cause a decrease in sperm motility and viability. This may be linked to poor queen quality as well. A well-mated queen (one that mates with many many drones of good quality) will have a colony that is vigorous, one that gets up early in the morning and forages on a wide variety of plants. A poorly mated queen (one that makes with few drones or drones with poor sperm) will have less genetic diversity in her daughters and have a more sluggish colony.

Mites

In the last two decades, bees have been attacked by Varroa mites. These mites literally suck the blood of the bees. This weakens them and they die younger and often with a heavy infestation, the hive can die out. The female Varroa mite sneaks inside a honeycomb cell with a baby bee and attaches herself to the larva just before the bees cover it with wax. Inside the cell, the female will lay one egg, a male who hatches out a few days later. They mate and she can lay one egg every four days after that. Generally the mites are more attracted to drones (the male bees) because they are in a capped cell longer. Once the drone bee emerges from the cell, the Varroa males will stay attached. The females will search out another larva to attach to with in the hive.

Beekeepers have a number of methods for dealing with Varroa. Most commercial beekeepers use pesticides that attach the mites but are not toxic to the bees. In the US this is usually in the form of strips or pads that are placed on the hive. Oxalic acid is an alternative treatment that is legal in most other places outside the US and involves heating up the oxalic acid and vaporizing it. Whatever choice a beekeeper makes, the miticide is on the bees and residue is on the wax and any uncapped honey or pollen the bees collect.

Why does this matter? The bees will ingest the small amounts over time and it will get in to the bodies of larvae and while not fatal, can affect reproduction and their immune system.

All beekeepers remove the honey for people before applying any miticide including the more organic options. Generally the bees that migrate are not the bees that make honey for people.

Viruses

Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus (IAPV) has been linked with CCD, yet it is clearly not the cause. IAPV in the US predates CCD by at least four years. IAPV in conjunction with the fungus Nosema cerenae was thought, for a short time, to be the cause of CCD, but more research has shown that this combination may be present in almost all of the hives affected with CCD, but not all CCD hives have both and some hives that have both don’t collapse. What is more likely is that a hive with CCD is sick and this virus and this fungus are both infections that the hive cannot fight.

Last year a new virus, Invertebrate Iridescent Virus and Nosema might be the smoking gun of CCD and while the preliminary research looks promising, it is still in the very early stages. Hives deliberately infected with both seem to get CCD and they can be rescued by treating the Nosema. However, if this is what happens outside the lab and if all CCD colonies have both of these pathogens remains to be seen.

Beyond CCD

The bottom line is that that CCD is a mystery and will probably be found to be a combination of factors, a perfect storm of factors like stress and disease take out a hive slowly, piece by piece.

There are other factors influencing the decline of bees. Weather can affect bees tremendously. Late springs, early frosts, floods all these affect honeybees. Also forage, what the bees eat could be a huge factor in honeybee health. In the US we are seeing a huge decline in the number of species of flowers that are native and an increase in the number of non-native species.

And not forgetting that honeybees are not native to the US, they are a canary in our coal mine telling us that something is wrong. Are we going to listen?

Could this be part of the answer?

https://planetsave.com/2010/10/09/mystery-of-honey-bee-colony-collapse-solved/

Thanks for your link David.

While it looks quite promising, even the study’s authors, as I mentioned, are cautious. It may, once again, be just a symptom. More research is being done as I write to determine if this is the smoking gun of CCD.

While Colony Collapse Disorder is catching the lion’s share of headlines, clearly there are other forces at work. Check out this story on bees dying in paradise: https://insteading.com/2011/04/04/bees-in-hawaii/