“No. No, no, NO! ARGHHH!”

This is typically not the sound you want to hear coming from the squash patch. But I had reached my wit’s end and was throwing a (teeny tiny) hissy fit over my plants (maybe). With a desire for food security and self-sufficiency, I had planted about 30 Hubbard squash plants — a breed renowned for its long storage potential. Visions of fall harvests danced in my head as they sprouted and began to vine across the ground. But then the vine borers came. Then the squash bugs, and then a drought — before I had even seen the first female flower, every single one of the vines was dead and withered on the ground.

Disappointed and frustrated, I ran to my seed catalogs for succor, scouring the squash section for a “better” variety, hoping I would have success next summer. The following growing season, however, was a case of deja vu, with the vine borers, squash bugs, and drought decimating my patch of Buttercup Pumpkins.

Again, I ordered seeds. Again, I planted a new variety in a new spot that was lovingly mulched and fertilized. Again, the bugs and weather conditions claimed their victims.

Having now planted for three years with nary a mature squash to show for it, I, again, dragged myself back to the seed catalogs, pleading with the florid variety descriptions to give me an answer. My husband, after watching this sad display of insanity for years, laid his hand on the magazine and looked me in the eyes. “You’re looking for the perfect squash, but you’ll never be able to order it.” He closed the catalog. “You’re going to have to make it.”

Thus, I began to explore the weird, wonderful, and wild world of landrace gardening. In this uncharted territory, there are no variety names, there are no seed packets with pretty descriptions, there are no money-back guarantees, but there may just be a squash that can survive and thrive on my dry, hot, insect-riddled hill.

What Is Landrace Gardening?

Landrace gardening is a method for breeding super hardy, site-adapted plants for your garden. As you know, the wild plants and weeds that surround and invade your garden need no help living. Though some of our garden plants need their botanical hands held, the dandelions, lamb’s quarters, and purslane seem impervious to whatever weather and pests throw at them. What landrace gardening endeavors to do, in essence, is give our chosen, domesticated varieties of vegetables the same vigor as undomesticated wild plants.

That is no small feat, and it involves a lot of up-front costs with hopeful, long-term payoffs far, far down the road. In fact, the landrace plants breeder needs to disregard the boundaries of cultivar and variety, and instead, mix as many different genetic potentials together as possible. Then the landrace breeder spends the following years selecting and refining the best traits from the wonderfully diverse results of their cross-breeding. The plant breeder will eventually able to get a new variety stabilized (producing near-consistent results). As long as seeds are grown out and selected every year, they’ll always be adapting to their environment.

How Do I Get Started?

The first step in landrace gardening is to know what species of plant you want to breed — and in this case, knowing the Latin is important. Whatever plant shares that Latin name can be included in your genetic pool (or intentionally excluded, if you don’t want them). This step this will add some genetic diversity to your landrace crop.

If you want to work with muskmelons, for example, you’ll be working with Cucumis melo — a group that gives us cantaloupes, crenshaws, casabas, honeydews, pocket melons, and Armenian cucumbers. Though those plants are seemingly different, they are all the same botanically speaking, and can all cross-pollinate. You can either gather from across the domestication spectrum for a super wild mix, or make sure to avoid the cultivars that display characteristics you don’t want (such as pocket melons, which are fragrant but have no flavor).

Next, establish your goals. Do you want a muskmelon that is cold-tolerant for your northern garden? In that case, you might try to look for early varieties that have already been selected for quick-maturity, or try to seek out seeds from northern growers.

Now it’s time to start collecting germplasm (raw breeding material) … that is, your seeds.

The first way to get your seeds is the most labor-intensive, yet may be the most rewarding. To get a potent genetic starting point, you’ll have to collect as many different varieties of a specific type as you can. I strongly recommend seeking out open pollinated and heirloom varieties when at all possible.

Though there’s nothing wrong with a true hybrid variety made the old-fashioned way (two varieties cross-pollinated by wind or insect), many hybrids from big breeders have been tampered with in a lab and will frustrate your efforts. They may produce sterile seed, be genetically modified, or have sterility programmed into their male flowers resulting in poor pollination and low fertility for offspring.

The second way is to purchase landrace seeds from a plant grower who has done the bulk of initial hard work for you. Of course, these seeds, no matter how genetically diverse they are, were obviously not grown in your garden, so they’ll still need a lot of work. Basically, these mixes get you a year or so ahead. Even with their diverse genetics, you’ll still have to go through the necessary planting and selecting process through the years that follow.

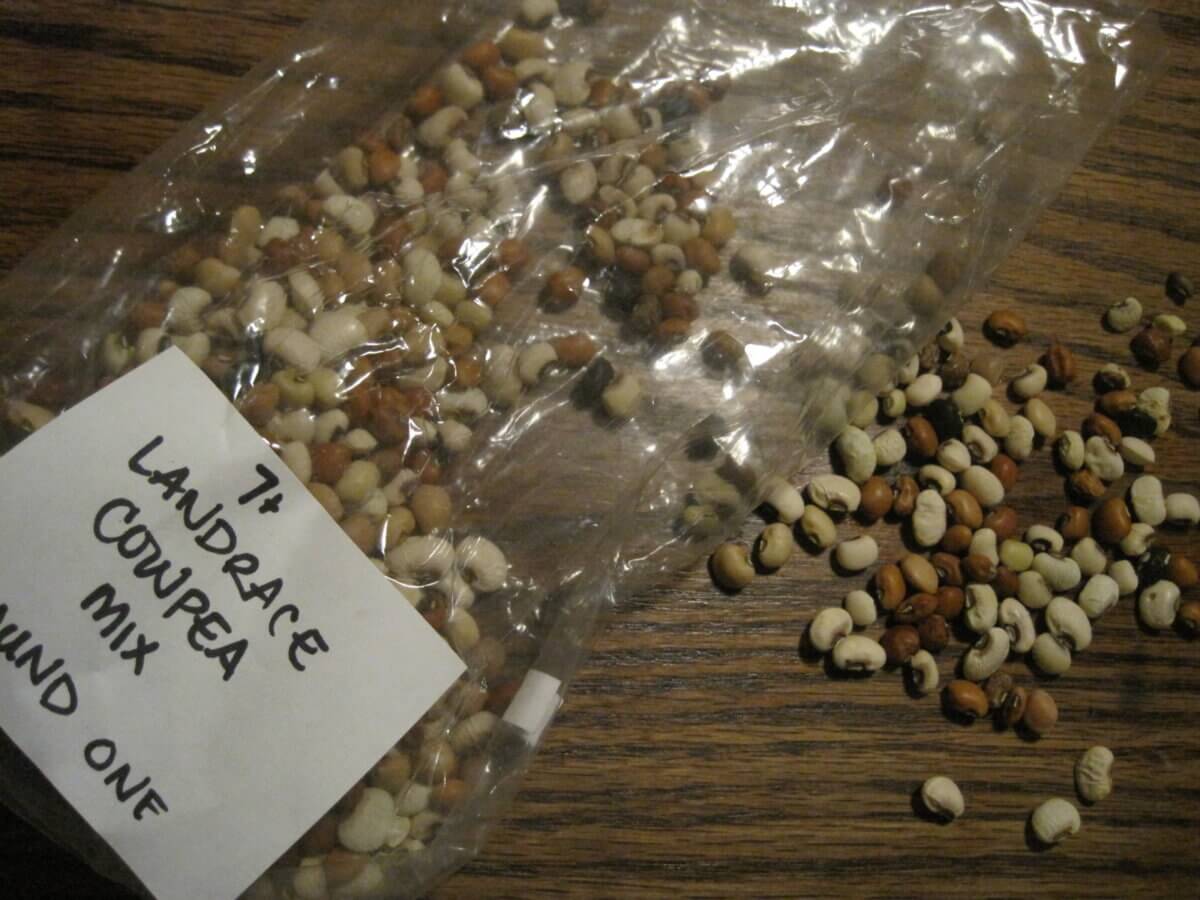

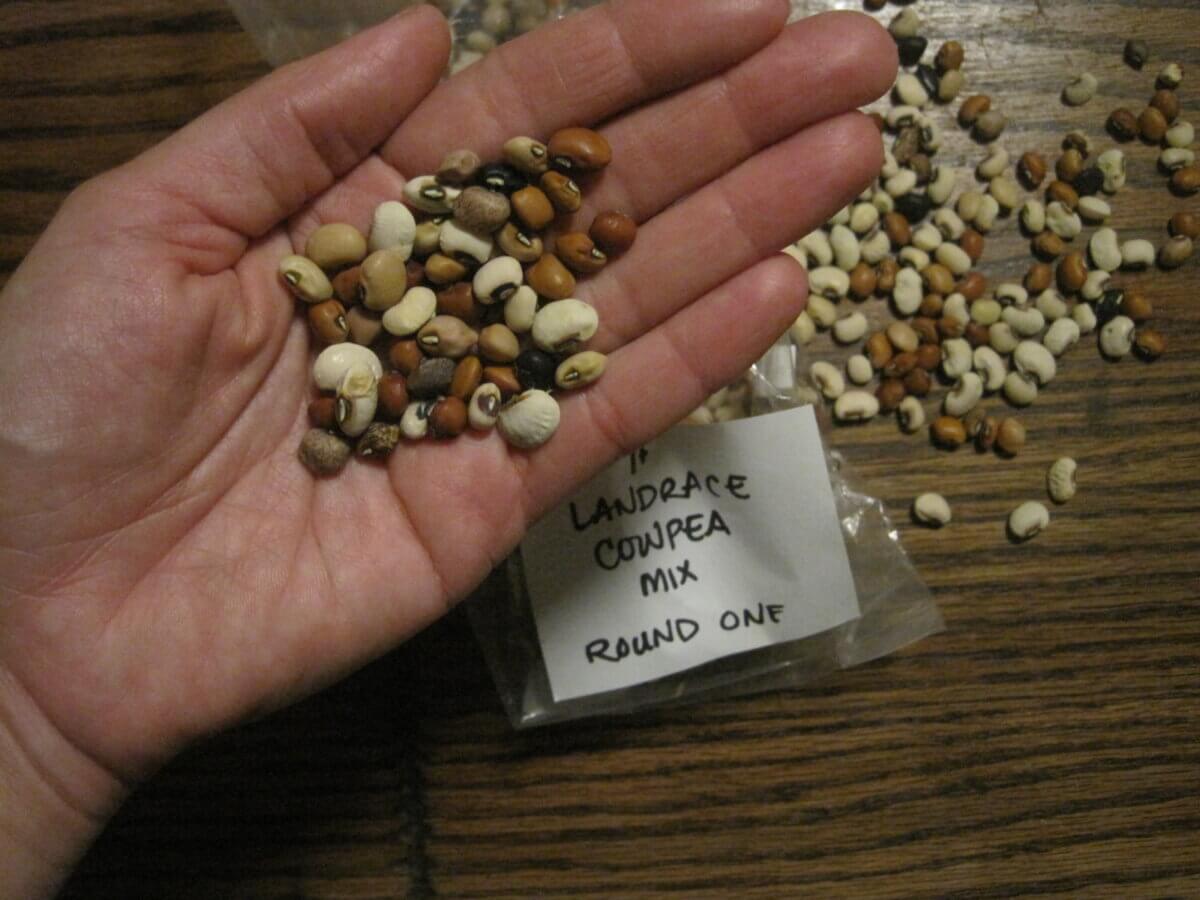

Landrace seeds aren’t available at your normal garden store, but they are available to those who know what to look for. You can sometimes find them listed as grex, landrace, or ultracross. I’ve listed several websites at the end of this article that can give you specific places to either buy or request landrace mixes of seeds.

Now What?

So, let’s say you’ve gathered bunches of different varieties. Now it’s time to plant them. This isn’t your normal planting, however, but a rather brutal, Hunger Games-esque planting where many aren’t going to survive. You see, the whole point of developing a landrace is, as I’ve already explained, to breed resilience, hardiness, and vitality back into a food plant. That means, no coddling. If some of the plants are weak while others are still going strong, you have to let the weak ones wither away and take themselves out of the genetic pool. So when you plant, plant more — far more than you think you’d ever want.

I think I can best explain the rest of the process by sharing my own efforts as example.

As mentioned in my introduction, the plant at the forefront of my own landrace breeding efforts is the winter squash. The weather and insect pressure on my Ozark hill is bad to put it mildly. In the seven summers on my land, I’ve been able to get a whopping total of two winter squash fruits to maturity before their respective vines succumbed.

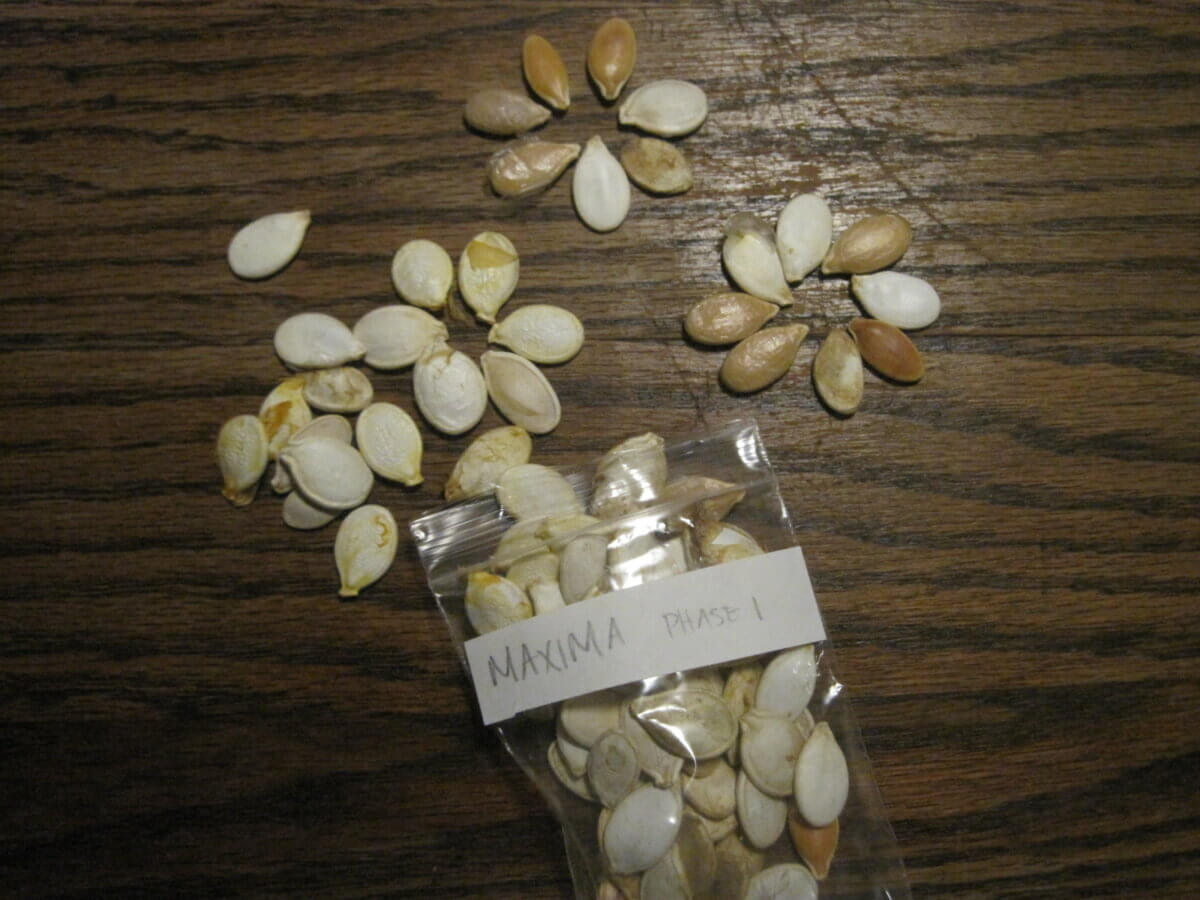

I have since learned that the winter squashes in the Cucurbita maxima species (such as Hubbard and Buttercup squash) are susceptible to squash bug infestation, while C. moschata squash (such as Butternuts) are especially resistant to their attacks. With that in mind, I’ve spent the winter finding other seed savers in the Ozarks (not always an easy task) and trading for some of their open-pollinated seeds of the C. moschata persuasion. I have now collected more than 10 different cultivars, ranging from Waltham Butternut to Seminole Pumpkin, and have gleefully mixed them all in the same jar.

In the spring, I’ll be planting at least one hundred plants (or more, if I can fit them) in my deeply manured and mulched “squash battle royale” garden. Then, I’ll have to stand by as the strong raise their vines and the weak succumb to the bugs and drought. Whatever survives will be allowed to flower freely and cross-pollinate with the other survivors.

In the fall, I’ll collect whatever matured squash I have been able to raise (hopefully more than two). As we eat the harvest through the winter, we’ll save all the seeds we can, refilling my C. moschata jar with the first round of cross-pollinated seeds.

The real work will come the next summer, when the mixed-breed squash go through the same process as their parents. This time when we gather the squash, we’ll label them and take notes on their growing vigor, flavor, texture, and storage potential. The squash that had the best qualities will be selected over any that didn’t taste so great, and their seeds will be the winners that reenter my jar.

As I continue the process year after year, I will continue to work on refining the best of the best. The end result will be … well, there’s never really an end result, as the process will continue with every passing year. The squash will always be responding and adapting to their environment, making them stronger and more resilient in the same way that weeds of the field are continually being naturally selected by their environment.

Further Reading

Though this is but a brief introduction, I hope it has shown you the exciting potentials and long-term vision shared by landrace breeders the world over. We’re not really revolutionaries or innovators. Instead, we’re going back to basics, and growing plants the way gardeners used to well before there were seed companies, trade-secret hybrids, or expensive seed packets.

As you’ll see, there are many others doing this work. As you do your research, check out the links below to learn more, find yourself some seeds, and get planting.

The Open Source Seed Initiative is a great resource for finding your seeds. Their big mission is to keep seeds, and the rights to breed them, available and open to anyone who wants to grow a garden. Though it’s not a seed house in its own right, it’s a marketplace that points in the right direction. They have several landrace varieties listed, though you’ll have to follow their links to acquire the seeds through catalogs or websites that offer them.

Going to Seed organization seeks to collect and redistribute potential landrace mixes of seeds to prospective growers. You can get your own packet of the seeds for the price of shipping, or you can donate some of your own seeds to their collection in exchange for some new seeds.

Carol Deppe, author of Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties, has several of her own landrace mixes and cultivars available through her seed company, Fertile Valley Seeds.

Joseph Lofthouse is one of the leading voices in the landrace vegetable movement and from Utah. He has written extensively about landrace experiments and efforts in his book Landrace Gardening, and in many of his articles hosted over at Mother Earth News. You can often find Lofthouse Strain vegetables listed in some of the other websites in this section; products of his diverse breeding efforts.

Utopian Seed Project is based in North Carolina. This project seeks to breed and trial new and experimental varieties and crosses of food plants that are locally adapted to their region. They have been trialing a series of plants they have termed ultracross –hugely diverse, “step one” mixes of as many varieties as they can mix. Their Ultracross collard seeds have been available from the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, and they have been working on okra and cowpea as well.

Seed Savers Exchange is open-to-anyone and lists thousands of varieties for hundreds of plants, all grown and offered by growers just like you. You can either use the exchange to gather different varieties, or (sometimes) find landraces bred by growers in your area. If you’re hoping to gather seeds to breed your own landrace, I recommend disclosing your intention to the folks you exchange with. Some may be more than willing to contribute seeds to the cause, while others may only want to share their precious, rare strains with people willing to help preserve them untampered.

Leave a Reply