Children pick these leaves out of the lawn in idle fidgeting. The plants crowd edges of streets and sidewalks. Counselors fashioned tiny boats from them at summer camp — with an acorn cap as hull and the omnipresent leaves for sails. They’re at your doorstop, the edges of your garden, and in the park.

Watch The Video

The commonplace appearance of this plant has made it all but invisible. Yet it is an abundant food more nutritious than spinach, easier to grow than lettuce, tough-as-nails in any growing environment, medicinally useful, and as a non-native species, impossible to overharvest.

There is probably no wild edible more ubiquitous than the one I want to share with you today, but I guarantee at least some of you have no idea what it is called.

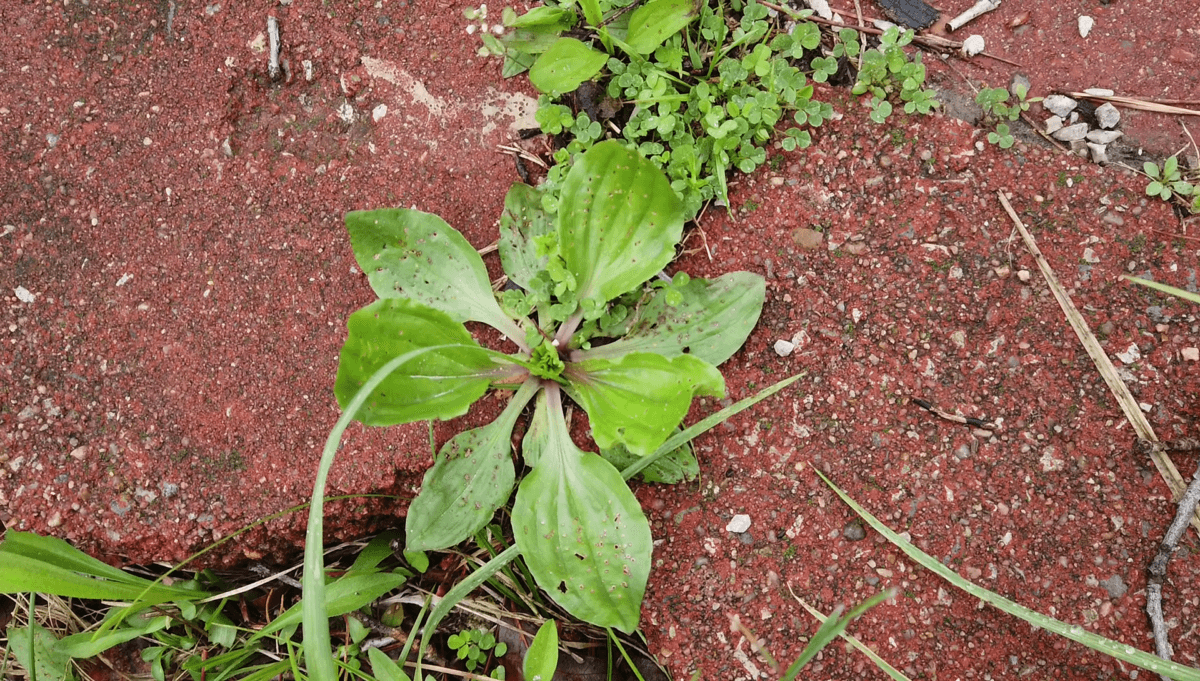

Do you recognize this plant? I bet you do. I spent years of my life walking all over it without knowing.

But I’ll tell you now. It is the lowly, humble, under noticed plantain. The members of the Plantago genus are everywhere, and offer many gifts.

Finding and Identifying Plantain

First off, we have to clear up some terms. The low growing herb that is the featured plant of this article is very different from the starchy, tropical, cooking banana that is (inexplicably) also called plantain. I have not been able to discover why these disparate plants were given the same title — if anyone has a clue, drop it in the comments below.

Plantain (the herb) is a plant that is common across Europe and Asia, and used widely in the associated medical traditions of those regions. It made its way to the United States along with colonialization. Though it’s not clear if it was planted intentionally or carried along in the droppings of livestock that were lugged across the pond, once it arrived, it was here to stay. Several Native American nations named this new-found plant “White Man’s Footprint” in a testament to its ubiquity.

In the modern day, finding plantain is a cinch. It has spread across the United States in their entirety, growing from east to west coast, and from the frosty north all the way to the humid south. Needless to say, you can’t overharvest it. It grows readily in any disturbed soil it can find, and it isn’t picky about location or soil compaction, either. Shade, sun, fluffy loam, or hard-packed clay; plantain will happily set up camp and grow lush and green. You can easily find it in the garden in the spring and summer, or alongside any foot trail year round. It’s an evergreen perennial, too. In my Zone 6 homestead, there are plantain rosettes scattered across my land throughout the winter. I don’t disturb them then, though. They’re not actively growing, and they’ll provide a lot better harvest once spring weather gives them the go-ahead to grow again.

There are two main species of plantain that you are likely to encounter.

Broadleaf Plantain (Plantago major)

Probably the most common and widespread is Plantago major, or broadleaf plantain. It bears broad, leathery-feeling leaves that grow in a basal rosette. They are simple, untoothed, and can vary widely in size, from an inch long and wide to leaves bigger than my hand. Notably, for members of the species, the veins in the leaves are parallel. The base of the petiole often has a wine-red color that fades to green by the time it gets to the leaf proper. And notably, the leaves and stems are lined with distinctive, white, string-like veins that stretch when the leaf tissue is ripped apart (a great key identification feature).

From April to October, the flowers grow in underwhelming, nubby green spikes that shoot out from the center of the rosette. They’re commonly seen as a symptom of an unmowed lawn rather than a flower in their own right.

English Plantain (Plantago lanceolata)

Plantago lanceolata, sometimes called English plantain, ribwort plantain, or narrow leaf plantain, grows in the same regions and with the same tenacity. On my land, the two species grow side-by-side, spoiling me for the choicest leaves.

Like broadleaf plantain, they grow as basal rosettes of leaves. Also similar are those distinctive, parallel veins and long petioles. Unlike broadleaf, English plantain is a bit hairy in both appearance and texture.

English plantain flowers are different than broadleaf plantain. They grow at the end of a long, green flower stalk, topped with a brownish, cotton swab-like head and ringed with tiny, white flowerets that bloom from April to October. They’re easy to overlook, but when viewed up close, I contend they have their own subtle beauty.

Plantain Look-Alikes

If you are new to foraging and have only begun building up your knowledge of plants and their traits, it is possible you could confuse plantain leaves with different species of domesticated lilies. Most lilies are toxic and should not be consumed, and plantain does have a passing resemblance to them when neither are flowering. Lilies notably lack the fibrous strings that are so distinctive to the Plantago genus, and a novice may not be aware of them. As I have said many times, and in our Ground Rules For Foraging Safely video, if you don’t have complete confidence in a plant’s identity, you’re not ready to eat it yet.

So, if you feel that you don’t have a good grasp of identifying plantain by the leaf alone this season, wait until the plants bloom. The underwhelming blossoms are a surefire way to distinguish plantain from any of the showy blossoms of the lily family. Take plantain’s long growing season to get to know and identify it in many settings, and you’ll be ready to harvest it at any point.

Harvesting Plantain

As you have already read, plantain has a knack for growing where little else wants to grow. It can often be found at the edges of sidewalk, paths, bike trails, and pretty much anywhere that feet have trodden the earth hard. As such, plantain is often growing in places that are awash with the toxins, pollutants, and poisons that we humans tend to leave on the ground in our high-traffic areas.

When you go out to harvest plantain, you should steer clear of the plants growing directly alongside high-traffic urban areas. It’s too likely for them to be contaminated. It’s far safer to pluck the perfect leaves rising freely in your backyard or in an abandoned field.

Flea beetles and their relatives like to nibble tiny holes in plantain leaves through the summer. It doesn’t affect the quality of the leaves if there are a few holes, but older leaves might be positively Swiss-cheesed. Thankfully, it’s such a prolific grower that you can still get fresh leaves from the center of the rosette in such cases.

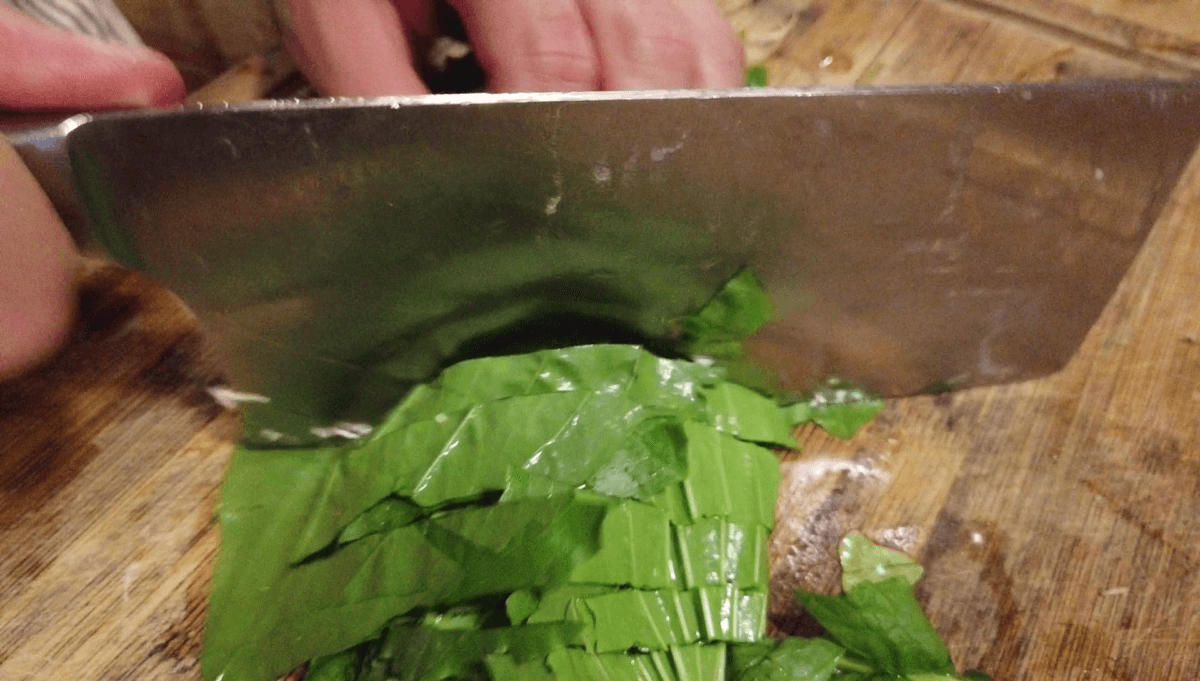

Now all that said, once you find plants good to pick (that shouldn’t be hard) you’ll have a wide array of kitchen possibilities open up to you. Let’s head to the kitchen and have some fun.

Cooking and Using Plantain

You can eat plantain as freely as you would kale or spinach, and with many of the same health benefits. Flavor-wise, it is mild, not bitter, green and vegetal, and somewhat unobtrusive to the palate. Some foraging books say that the young leaves have a lemony flavor, but I have never experienced this, so if you expect the same bright tang of a wood sorrel leaf when you chomp on a young plantain leaf, you’ll be disappointed. Likewise, a plate of boiled, unseasoned plantain leaves won’t wow anyone at the dinner table. But instead of seeing this as a detriment, think of the greens as a healthy, blank palette to spice up at your whim.

If you’re a fan of green juices or green smoothies, plantain is happy to become the cost-effective alternative to your pricey organic kale or wheatgrass. Just blend it or juice it, and mix it with fruit juice as you would other greens, and enjoy the health benefits.

Plantain leaves taste good sauteed like kale or spinach, but they will turn a somewhat drab, olive-green color when heated. Blend them with other greens or bright red peppers, and the dish will look livelier.

Many wild food cookbooks will say that you should only use the young leaves because they are more tender, but I honestly don’t listen to that. Instead, I pick leaves of all sizes and shapes and development. If you cut off the tough, wine-stained stem, then slice the leaves perpendicular to their thread-filled veins, they are all easy enough to chew.

Now, if you would like a whole article worth of ideas on how to use plantain leaves, head on over to our earlier video/article on some inspiring ways to use wild greens. Plantain fits perfectly into any of the recipes listed there.

For a particularly plantain-perfect preparation, however, I have to add one more idea. Plantain leaves make absolutely excellent kale — er, plantain chips. I prefer them 100% to kale chips, as their veiny structure becomes a boon, rather than a detriment during the cooking process, and helps holds the leaves together. Plantain chips are melt-in-your-mouth crispy once completely cooked, and leaves of any size can be used. Here’s an easy recipe online — honestly, any kale chip recipe works.

Finally, plantain can be dried and used as a base for a wild tea as well. On its own, it’s a little vegetal tasting, but when combined with red clover blossoms, blackberry leaf, and wild bergamot, it’s particularly nice and offers balance. We’ll have a full article on wild tea blends soon, so keep an eye out for that.

Medicinal Uses of Plantain

Though we are largely ignorant of plantain’s identity nowadays, it wasn’t always so. About four generations back, it was well known as a healing herb in the United States. But you can go even further back and find it mentioned as a healing plant in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliette (Act 1, Scene 2, for those interested). Plantain has been so widely studied in the past that it was placed on the U.S. government list of herbs that were labeled GRAS: Generally Recognized as Safe.

Now, before I go on, I suppose I’ll have to emphasize that, as with all online health advice, take my recommendations for what they are — tips from a stranger. You need to do research for yourself before depending on them. All the same, there are some notable uses for plantain that make it a bit of an on-the-go medicine chest for those who know how to use it.

Stomach Issues

Many folks have actually consumed plantain weed as an OTC treatment, but have no idea they have. The main ingredient in Metamucil is the seed of a cultivated variety of plantain, P. psyllium. The seeds of any plantain, however, can be used for their mucilaginous and mildly laxative properties. Strangely enough, a tea made from the leaves is astringent and has the opposite effect — it was used in the past as a mild anti-diarrheal.

Insect Bites & Stings

Now aside from stirring the seeds into orange juice, probably the most common first-aid use of plantain is as a field poultice for insect stings. If you’ve run into the unfriendly end of a wasp, yellow jacket, or bee, plantain is probably waiting at your feet, ready to offer up its leaves. Merely find two clean leaves, chew one into a gooey mess, spit it out onto the other leaf, and apply to the sting for relief. You would be surprised how much ouch this spit-poultice can soothe. I imagine this is due to plantain’s ability to draw out material when applied to the skin. Herbalists have used it to draw infection out of a wound, venom from a bite, even splinters from deep within the skin.

Wounds & Cuts

Old plant names often give clues to how they were historically used … and how they might still be used today. Plantain was once referred to as soldier’s herb, a nod to its past use as a wound-treatment on the battle field. The Omaha Indian Nation was known to crush the leaves in oil and apply the mixture to wounds to prevent scarring. You can also make an ointment in a similar tradition by infusing plantain leaves in oil and blending your own healing salve. We’ve got a whole article on the process over at Insteading, if you’re interested.

Happy Foraging

Now with all that shared, I hope I have given you a good introduction to this under noticed plant, as well as cultivated a desire to know it better. I can’t think of any better send off than this perfectly appropriate quote from herbalist Rosemary Gladstar.

“For anything to be this common, nutritious, safe, and effective, not to mention free for the picking, it truly is a gift to humankind. If Plantain put on a fancy name, donned an exotic blossom, and hailed from anywhere other than our own backyards and empty fields, we’d call it a super food, extol its virtues, and put a hefty price tag on it.”

I hope when you see this “weed” springing up around you, you are able to greet it as friend and aid, and not as an annoyance. I’ll be out there with you, plucking, drying, and eating plantain with gusto and gratefulness.

Sources:

Missouri Wildflowers, Edgar Denison

Herbal Folk Medicine, Thomas Broken Bear Squier

Rosemary Gladstar’s Medicinal Herbs: A Beginner’s Guide, Rosemary Gladstar

Thirty Plants That Can Save Your Life, Douglas Schar

Leave a Reply