I was going to call this article “How to Grow Turnips” — but knowing how such a title may cause those who don’t know turnips to gloss on by, I wanted to make more of an impact. Turnips aren’t very popular. Most folks don’t know turnips well. I would hazard a guess that many haven’t even tried turnips, and their closest brush with this oft-ignored garden plant is to idiomatically say someone easily fooled or gullible “just fell off the turnip truck.”

(I would change that idiom to someone easily fooled is someone who “just fell off the smartphone truck” but I digress).

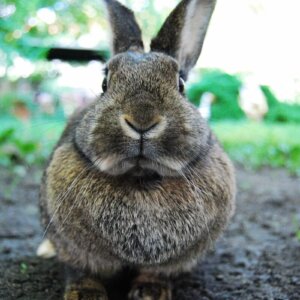

Turnips are one of my favorite vegetables to grow. They are dependable, easy, delicious, productive, and give you two vegetables for the price of one seed. Even though they have fallen out of popularity, they deserve the same rank as the estimable tomato that graces every garden and garden catalog.

Basically, “All I am saaaaayiiiiing is Give Turnips a Chance.”

If Turnips Are So Great, Why Does No One Eat Them?

Turnips aren’t usually on the menu. It’s not like you can go to a drive-through and ask for turnips, nor will you see them sauteed and garnished in the chef-iest way at a high-scale restaurant. I’ve only been able to find turnips at a Lebanese restaurant that pickled them with beets and included them in their falafel wraps (they were delicious, I might add). So you may be asking, if turnips are so great, why does no one care?

Turnips have a long past with humans. Brassica rapa subsp. rapa was first domesticated as a root crop in Central Asia thousands of years ago. From there, it spread both east and west, becoming an important food crop in Europe (where it was important to both the Greek and Roman Empires) and China and Japan. Closer to our own time, turnips were an important crop in the American South, where they were able to produce an edible crop faster than pretty much anything else.

Through the ages, undoubtedly because of how easy they are to grow, turnips became associated with animal feed, peasantry, lower-class, immigrants (and turnip trucks that easy-to-fool, naive folks fall off of). An ancient European line of thinking was that things that came from the dirt were for the poor and low classes (i.e., vegetables) and things that came from the air were fore the upper-class (i.e., wild birds). Even though the poor health of the upper classes was partly due to this snooty behavior (well, that and the inbreeding and bloodletting and such), the modern, learned prejudice against eating your veggies probably has roots in this tradition.

Dumb, I say! Who cares if turnips aren’t all that popular? These are a nutritious, easy-to-grow, fast-growing, double-whammy of a crop that gives you both greens and versatile roots. Forget the past’s preconceived notions of what is or is not “good enough” for proper human consumption, and invite turnips into your garden.

Turnip Varieties

We’ve got a whole ‘nother article on different types of turnips and you can find it here. Whatever variety you choose, it’s important to know that turnip cultivars come in two flavors — either focused on huge leaf production or root production. Just like beets and Swiss chard, turnips and leaf turnips are the same species of plant domesticated in two different ways.

I personally will always grow root variety turnips. Though the leaf varieties make huge leaves (and I do mean HUGE), they produce woody, not-so-tasty roots. Meanwhile, the root varieties make the delicious turnip part, as well as plentiful greens. To me it’s a no-brainer. I’d rather get two veggies from the same plant, than lose those tasty roots for the sake of bigger leaves. Root variety turnip leaves are sometimes more stem than green leaf tissue, which suits me fine. The juicy stems are absolutely wonderful stir-fried with garlic.

Growing Turnips

Some plants have significant challenges if you want to grow them well. Flea beetles delight in destroying eggplant. Onions get stunted if grass gets the better of them. Fava beans can’t stand heat. Many need extra care and planning if you want to get anything out of them.

Turnips, however, are not one of those difficult plants. They’re easy to grow. They want to grow. They’ll grow even in subpar conditions. All they need is a space to do it.

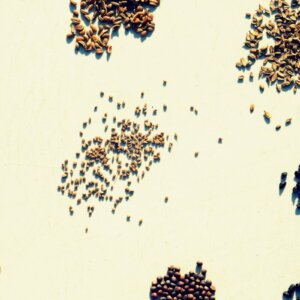

Turnips grow so fast that you can plant them at least twice a year. In the spring, they can go in the ground when you’re planting radishes and parsnips, right around the time the soil can be worked. Once they sprout (like radishes), thin them judiciously. Crowded turnips don’t make as big a root as nicely weeded ones. Now unlike radishes, they don’t bolt at the first sign of heat. They just keep on truckin’.

Wikimedia Commons

Pests

Flea beetles may nibble some holes in the leaves, but turnips never seem to be too badly affected. The two pests who might do serious damage are harlequin bugs (Murgantia histrionica) and voles.

Harlequin bugs will create misshapen, warped foliage and can kill plants if their numbers are too high. My best organic practices to fight them is to plant turnips in a totally different spot every year and disrupt their life cycles.

Voles, on the other hand, are difficult to stop once they find your turnips and begin eating them whole. My best organic practice for fighting voles is to have a good cat stalking the garden. Additionally, voles only eat my turnips once they get to harvesting size. Once the voles start moving in, I take it as my cue to start harvesting turnips before the voles can spoil them.

Harvesting

Throughout their growing, you can harvest a few leaves for greens. And of course, once the roots get to size (what size that is depends on the cultivar — I harvest my purple top white globe when the roots are around 3 inches in diameter), you can have a bonus harvest of the leafy crown.

Then once the summer heat has abated, you can plant turnips again for a fall crop where they should reach a decent size before frost. Frost won’t kill them. In fact, if you live in a region with mild enough winters, I recommend leaving a few of these cold-hardy plants mulched in the ground over the winter. For reference, my winters get down to -3 degrees Fahrenheit, and most of my turnips survive in the garden. Any colder, and you may need to use a root cellar. Since turnips are biennials, they’ll welcome you in the spring with regrowth, and the opportunity to harvest seeds and become turnip self-sufficient.

Cooking Turnips

Harvesting turnips is as simple as pulling them out of the ground, washing them off, and getting them in the kitchen, pronto! There’s good food to make.

The Greens

Don’t you dare think about tossing those greens. Unless the flea beetles have really done a number on them, they are succulently juicy, wonderfully green, and don’t have a hint of bitterness about them.

If you keep the long, thick stems (which you should), they are more like Swiss chard than spinach in texture. I think that’s a good thing. Cooked spinach becomes mush, whereas cooked turnip greens become something that still has a bit of backbone.

Traditionally, they are boiled, but I prefer to sautee them with garlic and a sprinkle of salt. Try them that way, and I think you’ll start appreciating them as much as I do.

The Root

The turnip root proper is a versatile vegetable. Raw, it tastes like a mildly sweet radish, and if grated, it makes an incredible base for a slaw. Roasted, its sweetness comes to the fore. Boiled and mashed, they’re not quite potatoes, but mashed turnips with a touch of butter and cream are decadent.

If you have a root cellar, turnips are a great candidate for long-term storage as well. Handled carefully, and with care given to protect other foods from their admittedly cabbage-y raw odor, they can last 4 to 5 months.

Final Thoughts

Turnips are one of my absolute favorite garden plants to grow and eat, and they’re a great “encouragement plant” for gardeners who have challenging weather, pest, or heat situations. They typically grow in un-ideal circumstances, acting as a balm on my sometimes garden-discouraged, drought-beleaguered heart.

I hope this article has given you a fresh perspective on this humble, undeservingly unpopular vegetable. If you’ve never grown them before, for whatever reason, try planting them this spring or fall and see if they don’t surprise you with how good they are.

Leave a Reply