The gardener’s greatest asset is healthy soil. No matter where you are or what you are trying to grow, taking care of your soil will help your crops.

Learning soil science can be overwhelming. It involves lots of chemistry, and you can easily get lost in technical details.

We are here to help, with this beginner’s guide to soil care. To have a successful garden you don’t need a Ph.D. in soil agronomy, you just need basic understanding of nutrients and pH.

Why Does Soil Matter?

Soil health is the foundational ingredient in all plant growth! Soil is more than just something that holds plants up—it provides almost all the essential elements that make up plant cells, as well as holding and delivering water. Organisms in the soil perform essential tasks of decomposition and nutrient recycling. Soil quality directly affects what you can grow and how well.

By the way, it’s soil, not dirt. Soil refers to the complex combination of organisms, minerals and organic material, unique from place to place, that makes up the land. Dirt is what gets on your feet and is tracked into the house—it is displaced and no longer has any of the complexity of soil.

There are two major things to check to find out how healthy your soil is: nutrient levels and pH.

Nutrients

Plants, like humans, need large quantities of some nutrients and very small quantities of others. We get our nutrients mostly from what we eat, and so do plants; regular fertilizing is essential to a thriving garden.

Fertilizers can be synthetic or organic, like compost, manure, and blood or bone meal. Nutrient levels in the soil change throughout the year, depending on what is being grown, and on other factors like rainfall and leaching. For best results, you should fertilize your garden every time you plant a crop.

The “big three” nutrients for plants are nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, or NPK, known as the primary nutrients. Secondary nutrients include calcium, sulphur and magnesium.

A complete organic fertilizer like manure will have roughly balanced proportions of these macronutrients. Synthetic fertilizers will have their nutrient information printed on the label.

Look for something that includes all six of the main nutrients, since some fertilizers only include NPK, or only include nitrogen. These supplements can be helpful to give your plants a boost during the growing season, but a balanced nutrient mix is important to start each crop.

The Importance Of Nitrogen

Nitrogen is the number one nutrient to keep track of, since it is critical to plant health but doesn’t occur in the soil without bacterial activity. Nitrogen is also water-soluble so it leaches quickly out of the soil, into groundwater, and is lost.

Most of the nitrogen on earth is gaseous nitrogen, in our atmosphere. To be available to plants, it needs to be “fixed,” or converted from elemental nitrogen into compounds of nitrogen and oxygen, called nitrates.

Nitrates are water-soluble and come in a form plants can absorb. Plants can also get nitrogen from ammonia, which is nitrogen bonded to hydrogen, and naturally occurs in animal and human urine.

Nitrogen-Fixing Plants

Some plants are “heavy feeders” that “eat” lots of nitrogen, while others need less. Some plants can fix their own nitrogen from the atmosphere via symbiotic bacterial colonies on their roots. The legume family is most well known for this, but other many other plants, like the red alder tree, also fix nitrogen. Successful invasive species like kudzu and scotch broom thrive in all types of soil because they are prolific nitrogen fixers.

When I first started gardening, I was confused about nitrogen fixing—do the plants actually put it in the soil, where other plants can use it? The answer is no—the symbiotic bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen to nitrate, a compound that is available to the plant, but that becomes stored in the plant matter itself, not in the soil.

So, for that nitrogen to be available to next year’s crop, you have to till in the green matter of the plant at the end of the season. For example, alfalfa is a nitrogen-fixing crop grown as animal feed. But since the whole plant is harvested and not much is left to till in, it doesn’t significantly improve soil quality for the next year. On the other hand, crops like peas and soybeans do improve soil nitrogen levels, because the seed is harvested with a combine for animal feed and the green matter is left in the field.

Micronutrients

In addition to the big three and the secondary nutrients, plants need small amounts of half a dozen or so other minerals, just like humans do. These include iron, copper, boron, and zinc, among others, Some nutrients that plants need in small amounts become toxic in large quantities. It can be hard to mix very small quantities of additives onto small pieces of land.

Boron, for example, is a mineral that helps strengthen cell walls in plants, and an acre of crops takes about ½ lb of boron as an additive. Too much boron will cause yellowing and withering and eventually stunt a plant.

That means that if your garden is 1000 square feet, you would need to apply less than 2 hundredths of a pound (.011lb) of boron to the whole garden. Imagine how hard that would be to spread evenly!

When I was gardening small plots I never worried about micronutrients. As long as you fertilize at the beginning of your season with a balanced fertilizer like chicken manure, there should be plenty of micronutrients available to your plants all season. However, if you are having puzzling plant problems like stunted growth, discoloration, or failure to fruit, checking your micronutrients is a great troubleshooting option.

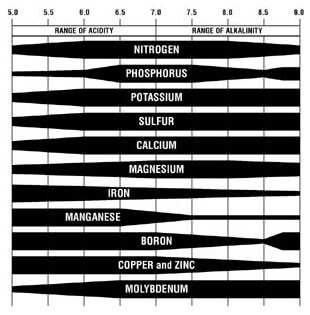

Soil pH

Knowing your soil’s pH is more actually more important than getting a precise read on the nutrient content, because pH dictates how available the nutrients in the soil become. Your soil could have a perfect nutrient balance, but with a pH too low or high the plants would not be able to access any of those minerals.

Most plants want slightly below a neutral pH of 7 for optimum growth, but a soil’s natural pH varies widely from place to place. Naturally-adapted varieties will have some tolerance for the indigenous pH.

In the Pacific Northwest we have acidic soils, but just a hundred miles away on the other side of the Cascade mountains, the soils are basic. It helps to know the general soil pH in your region, but your garden may be different. If you have just bought a new property or are beginning a garden in a new location, it’s good to check.

Unlike nutrients, soil pH doesn’t change much unless you change it yourself. If your soil is acidic, you can add powdered lime. If soils are alkaline, you can add sulfur to create sulfuric acid, or organic material that will create acids as microbes break it down, like peat moss.

Changing soil pH is a gradual process that usually requires soil amendments over the course of many years, usually at the beginning of each growing season.

How Do I Know What Is In My Soil?

Most components of soil health, including pH and nutrient levels can be easily tested in a lab. Agricultural extension offices almost always offer soil testing services for low or no cost.

They will give you instructions on how to take a sample and submit it. You can expect your results within a couple of weeks, and if you need help interpreting the results, extension agents are the best people to help. You can buy home test kits, but they offer variable and unreliable results.

You can also have your soil tested for micro-organisms in the soil, but these tests are more specialized and expensive. In Washington, our state extensions do not perform those tests, but private labs in our area do.

Since soil is so unique, labs work regionally rather than nationally. If you want to go this route, ask your extension agent for recommendations, or try this database on soil labs maintained by the National Center for Appropriate Technology.

Some indicators of soil health that don’t involve testing at all. People have been caring for soil in agricultural societies for thousands of years and there are many factors that help a gardener understand what is happening in their soil.

The performance of your crops is the number one indicator of soil health. Symptoms of nutrient deficiency usually start with discoloration or yellowing of leaves, poor fruit production, wilting, drooping or withering, and sometimes include blisters and other deformities.

It is not always easy to tell the difference between a soil problem and a plant disease, but if it has affected your whole crop at once, rather than starting in one place and spreading, it is likely to be a soil issue.

Other indicators that you can see and feel include soil texture, organic matter, organism diversity and water penetration. When you water your plants, watch to see if it sheets off the surface or if it penetrates readily. Poor water penetration can be a sign of compacted, heavy soil, low organic material, or drought.

The soil should be as light as possible for the type of soil you have. Clay soils will never be as light as sandy soils, but incorporating organic matter like grass clippings or manure will help make your soil more airy. Healthy populations of worms and other macro-organisms will also help aerate the soil, and diverse, abundant populations of worms and other bugs are a great indicator that you also have healthy microorganisms.

Soil Toxicity

Unfortunately, in parts of most cities, and even in some rural areas, the soil is contaminated with toxic metals and chemicals, like lead, mercury, petroleum and solvents. If you live in an industrial neighborhood, near a highway, or in a rural area near or downriver from industry, consider testing your soil for toxins.

If you are unsure about the history of your property or garden, do some digging! (Get it?) Look into county records, find out what uses your land is zoned for, talk to previous owners or neighbors who have been around longer. And when in doubt, get out a trowel and take some soil samples. To find a local lab that will run these tests, ask your extension office. They most likely do not do toxicity tests themselves but will know who to ask.

If you find that your soil contains one or more industrial pollutants, build raised beds to fill with imported soil, or look for a different garden location. Always wash your food before cooking. Cornell University has compiled these guidelines on common metallic contaminants, including some potential risks and recommendations for safety.

Polluted soil is a reality of life for many people, and by being informed about what your soil contains, you can take simple steps to limit exposure and still grow a garden.

A Note On Buying Soil

It is possible to buy topsoil, and many people choose to. It is a good option if you are overwhelmed by the idea of restoring very acidic, alkaline, rocky, or depleted soils, or if you are building raised beds and need to fill them, and especially if you suspect toxic contamination of any kind.

Buying soil can put your mind to rest that your plants are growing in clean soil with a good balance of nutrients, organic matter and pH. But it can get expensive if you have a large garden.

As always, check the labels on products you buy—the more information they provide the better. Reputable companies should tell you the percent organic matter, the nitrogen levels, and pH. Look for a mix that includes lots of organic materials. Check out this guide for more details on buying topsoil.

However, while buying topsoil makes it easier to get started with a garden, your soil still needs care throughout the season, every year, just like you care for your crops.

Ongoing Soil Care

Without care, even the best soil will get nutrient-depleted and stop producing great food. Depending on your climate and what you are growing, this may take years, or months. Throughout the growing season, watch your plants, and amend with fertilizer like compost or worm tea to give your plants a boost if they are looking yellow.

After the season every year, you need to do a few things to keep your soil healthy.

It is important to let your soil rest. By rotating the types of crops you are growing to different areas of your garden, you can help the plants themselves support soil health. Rotating nitrogen fixers with heavy feeders, like beans with corn, creates a symbiotic relationship over the course of several growing seasons.

Crop rotation is essential to pest control as well as nutrient management. Having fewer pests means less headache and a better harvest for you, but it makes your soil healthier. While organic pesticides in moderation can help a gardener, applying too much, or using harsh chemicals like Roundup can harm communities of beneficial microbes in the soil.

If you live in a cool climate, each winter is an opportunity for your soil to rest. To get the best benefits from a winter fallow, plant cover crops to protect the soil and add organic matter in the spring.

If you are lucky enough to live somewhere you can garden year-round, you still need to rest your fields, either in cover crops or as pasture every one to three years, depending on what crops you grow and how heavily they feed.

Soil Science Is Not Rocket Science

Soil science is a complex and technical field of study in its own right, that people spend lifetimes studying. Don’t let the chemistry and measurement overwhelm you. The bottom line is that by trial and error you will learn a system of amendments and soil care that works for your garden.

Pay attention to your plants and they will tell you if they need something different. Soil tests and pH are tools to help get clarity and troubleshoot when things go wrong, but they are not the law of the garden.

With a basic understanding of what is in soil and how it helps plants, you can navigate most problems and support healthy soil for many years in your garden. As always, don’t be afraid to ask for help, from extension agents, other gardeners, even university professors. If there’s one thing I know, it’s that soil science nerds are always happy to talk about dirt.

This is a great article. Very informal! Thanks for putting this together.

Many many Thank You

for all this information beautifully written to be understood by the novice gardener.

I now have a lot more confidence in taking care of the soil and the vegetables in my garden.

Many Blessing with much Gratitude to You

Samir Stjohn Touma.