I truly enjoy foraging in my neck of the Ozarks. As I venture out to collect the abundant wild spinach, pokeweed, and mulberries, my neighbors seem to think I’m mysteriously gifted with esoteric forest knowledge (which, of course, isn’t true), or just quaint and a little weird (which is actually pretty true).

But for all the strange plants I try (and sometimes succeed) to share with them as truly good food, there’s one that they already seem know, even if they’ve never foraged for it themselves. Somehow, this shrub’s famous reputation as both food and tonic has remained through the decades as knowledge of other just-as-useful plants has faded into obscurity.

That plant is the American elder, Sambucus canadensis. Sometimes, it is considered the same species as the European black elder, in which case its scientific name is Sambucus nigra.

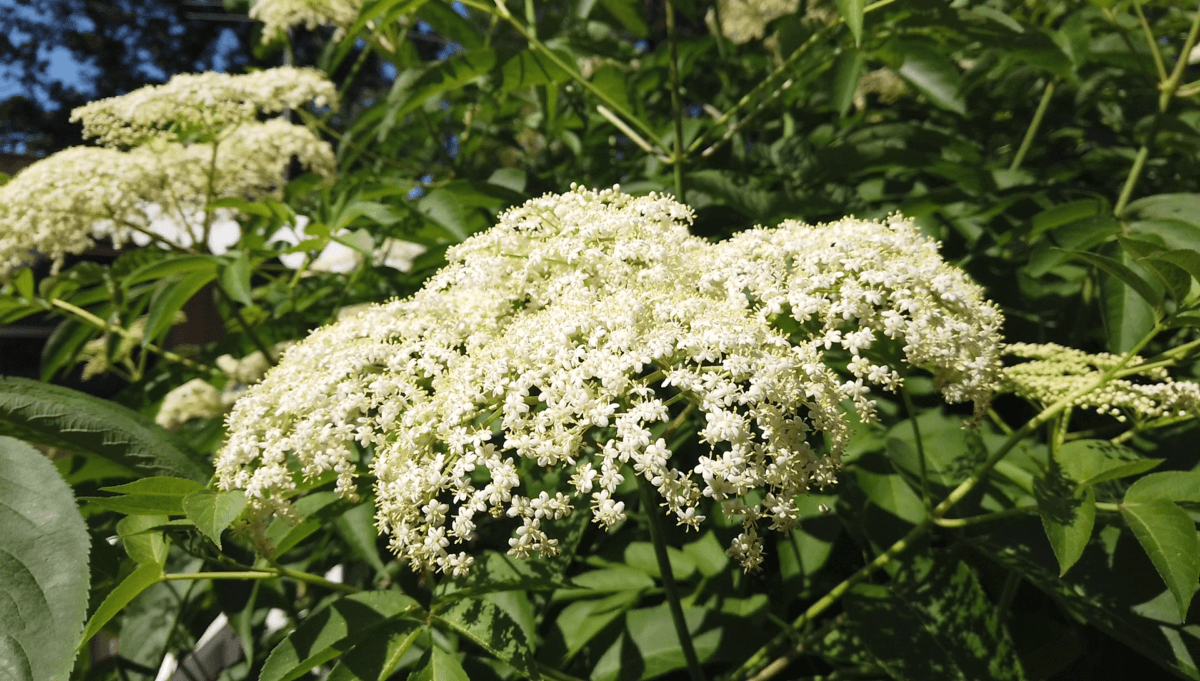

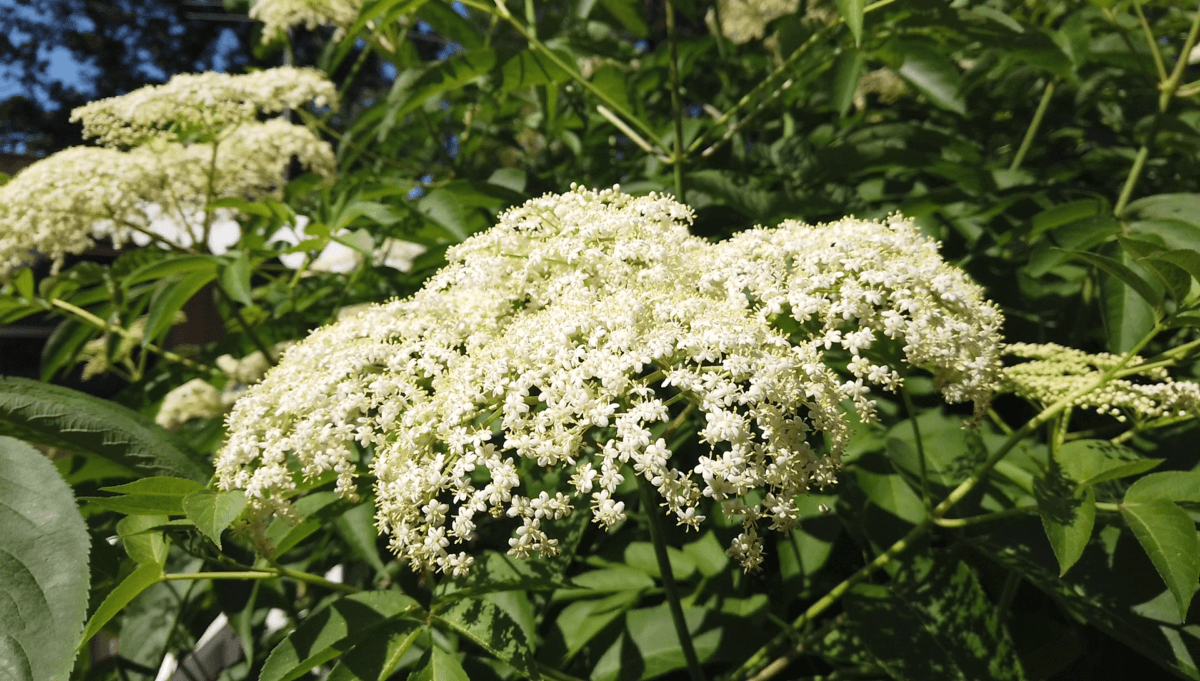

It lines the roadsides, hedges itself around the parks, and forms dense thickets wherever it gets the inclination. It’s the visual herald of the hot days of late spring, forming dense, creamy-white flower clusters that temporarily turn the blazing-hot forest edges into a visually incongruous summer snowball fight. Then a month later, those same forest edges are alive with birds, cramming as many of the shiny, dark purple berries into their beaks as they can.

It is into this sweaty, blazing-sun theater that the forager enters, ready to collect one of the wild’s many free bounties of food that are available to whatever man, bird, or beast has the knowledge to gather it. If you would like to be one of the surprising few people who both know about elder AND collect and use it, read on and join us. There’s plenty for all.

Identifying Black Elderberry

Elder is a large shrub that usually grows to a full 5 feet tall before it starts producing flowers and can reach up to 12 feet at maturity. It forms few branches, instead growing and spreading into thickets that can be quite dense. The bark is a light gray color with bumps across its surface. The stems can get thick, but they’re weak, and break easily. If you do break a branch, you’ll see that it is filled with a spongy pith.

It has compound leaves that are opposite, with usually 5 to 7 leaflets. Leaves can grow as large as 20 inches in length. The flower clusters (technically called “cymes” for all my fellow botany nerds) can get huge when they bloom in the late spring or early summer, sometimes containing hundreds of tiny, white 5-petaled flowers. The fragrance of elderberry flowers is unmistakable, and after all my years growing them, I still can’t figure out if I like its dusty, musky floral aroma. You’ll have to decide for yourself when you get shoulder-deep in them some spring.

When elder produces its small, shiny, purply-black berries, it really goes to town. To see a single elder berry is nothing to remark about as they’re just a little bigger than a peppercorn, but when you realize that they come in such outstanding quantities, you’ll forgive their diminutive stature. In a good year, the berry clusters weigh down their branches to the near breaking point, making the shrub look positively downcast as it contemplates the soil below its fruity spread. Depending on where you live, elder berries will ripen sometime between July and September, though some folks find good clusters later in the season (so long as the birds somehow haven’t finished them off).

If you live in the United States, finding elder shrubs shouldn’t be hard. There’s some species of elder growing in your area, nearly guaranteed. These plants are fond of moist soil with lots of sunlight, so the best foraging will be near rural roadsides (as long as they haven’t been sprayed), at the forest’s edge, along waterways and pond edges, or on fence lines.

Now, there are several different species of elderberry to be found in the United States. American elder is everywhere from Maine to Texas. West of that, there’s blue elder (Sambucus cerulea), in California, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico and Nevada, you’ll find Mexican elder (Sambucus mexicana).

There are also three different species of red elder (or one species, depending on what books you read) variously referred to as Sambucus pubens, Sambucus racemosa, and Sambucus callicarpa.

Note 1: Red elderberries are not the same as black and blue elderberries and need special preparations to be rendered edible.

I have no experience with any of these other species, and so I’m writing this article based on my foraging and use of American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis). If you have any of those other elders growing in your area, (such as blue elder, which is apparently the superior-tasting western counterpart to my Ozark-growing American elder) then please look up specific information on them by their scientific name and educate yourself.

Look-Alikes

Full-grown elder shrubs are distinctive, particularly when they are in bloom. There are few other shrubby plants that create anything resembling those huge pom-poms of creamy white, starry blossoms. Additionally, their large clusters of glossy, purple-black berries are unique. That said, the novice, indiscriminate forager with little plant knowledge may mix them up with other plants, particularly compound-flowered ones.

In his book Nature’s Garden, Samuel Thayer suggests it’s possible to mix up young, small elder plants with water hemlock (Cicuta spp.). They blossom around the same time, both have passably similar leaves, and share habitat. That said, this mix-up can only happen if you’re not paying attention while collecting spring blossoms, as the differences between the plants are clear if you know what to look for.

However, as water hemlock is poisonous, it’s worth knowing what both plants look like so you can forage with certainty. Here are descriptions and photos of both plants in bloom.

Water hemlock has large clusters of white flowers, but the stems are markedly different than elder — they’re smooth, hollow, and hairless.

Now, compare those photos with elder blossoms. Even though the blossoms may look similar, the bark, as we’ve already discussed, is bumpy, brown, and the stem is filled with pith.

There are more differences than the key ones noted. Green Deane has made a good list here at Eat The Weeds if you want to learn more.

As I and many other foragers always say, never put a plant in your mouth unless you are 100 percent confident in its identification. If you, personally, couldn’t confidently distinguish between the different plants pictured here, take the time to do more learning and research before you forage for them on your own. Better yet, find someone knowledgeable to walk with you and teach you in the field. Once you’ve met these plants face-to-leaf, you’ll be able to build the necessary experience and familiarity to safely forage.

Thankfully, the berries of elder are unmistakable. Water hemlock doesn’t make berries at all. And once you really know elder, I’m confident you won’t ever make the mistake of confusing it with anything else.

Foraging for Elderberry

Elder offers at least two different harvests for the forager, though the plant has many more uses than that if you delve into its history: music, dyes, medicine, and children’s toys. As far as this article is concerned, we’ll just discuss harvesting the flowers and ripe fruit.

The flowers are unmistakable. Huge white mounds of blossoms, sometimes covering a patch of forest’s edge. They start to appear at the beginning of summer (indeed, British folklore says that the English summer begins when the elder blooms and ends when its fruit is ripe). The blooms can be used for teas, jellies, and a flavoring ingredient in desserts. All you have to do is gather them.

It’s very easy to harvest elderberry’s huge flower clusters. The easiest way is to clip the whole thing off with a set of pruners, and throw it in a bag to clean later. This manner of harvest can be short sighted. All the flowers you cut off are, obviously, never going to finish becoming berries.

That said, there are a plethora of dessert recipes for elderberry fritters where the entire flower head is cut, dipped in batter, and deep-fried. Served with powdered sugar, it tastes like a honeyed doughnut.

I try to avoid too many sugary, deep-fried confections, however, especially if they take out my future elderberry harvest. Instead, I have my cake and eat it too by harvesting only fertilized flowers. The elder quickly drops any blooms that have done their job, so all you have to do is get a container and hold it beneath a cluster of blooms. A couple shakes, and all the fertilized flowers (and a fair amount of spiders and little beetles) will fall into your container like a tiny star shower.

Visit enough blooms, and you’ll soon have a heaping harvest. To dry (and remove all your unintended living stowaways), spread the blooms on a towel out of direct sunlight to preserve their musky sweetness for future use, or use them immediately in cakes or teas. I particularly like making sun tea with elderberry blossoms, lemon balm, and wild bergamot. For a special touch, scatter a few of the blossoms on top of the tea to serve.

Later in the summer — usually at the end of July for us here in the Ozarks — the juicy purply-black berries will ripen.

Note 2: Before I go into the details about the berries, I must impart to you that elderberries cannot be eaten raw. One or two won’t hurt you, but you can’t chow down on handfuls of elderberries like you can blackberries and strawberries. They must be cooked first so you don’t end up spending the evening on the toilet.

Ahem. Now back to the berries. The plants can create truly enormous bunches of berries, and in a good year, they’ll produce an overwhelming amount of pickable goodness. You can identify ripe berries when they are almost purple-black, and slightly soft to the touch.

They generally don’t all ripen at once, so if you’re out foraging in a wild area, you may need to revisit your elderberry thicket a few times to get all the berries you want. If you grow elderberries on your own property, you will have to contend with birds to get the harvest. They like elderberries as much as we do!

Some years, the birds also go after the green berries. I have seen them do this during drought-prone seasons. In order to protect my berries (or, at least, some of my berries) I’ve tied mesh bags over near-ripe clusters with good success.

To harvest berries, you can either use a pruner to lop off the berry clusters, or snap them off at their base where they meet the plant. You should plan on using, freezing, or preserving the berries for later use as soon as you can after your harvest. Like many good things, they don’t last long.

But don’t bother plucking individual tiny berries off the bunch, unless you want a total mess on your now-purple hands. Instead, the best way to freeze them for future harvesting is on a tray. Once the berries are totally frozen, they fall off the stems with a slight touch. Gather these totally frozen berries in a large container and keep it there until you’re ready to process them, be it for medicinal or culinary uses.

So, now that you have a beautiful bowl of bitty blackish-purple berries, it’s time to figure out how to use them. One of my favorite ways to preserve the delectable and medicinal properties of elderberries is to brew them in a versatile elderberry syrup. The messy process takes some explaining, so I’ll give you my recipe in the next article.

In the meantime, get out there and start collecting those berries. The birds will take them if you tarry.

Leave a Reply