It’s time for the next entry in our series of Homesteading Questions and Answers. As we get questions from you, we try to formulate the best possible answer to help you on your adventure.

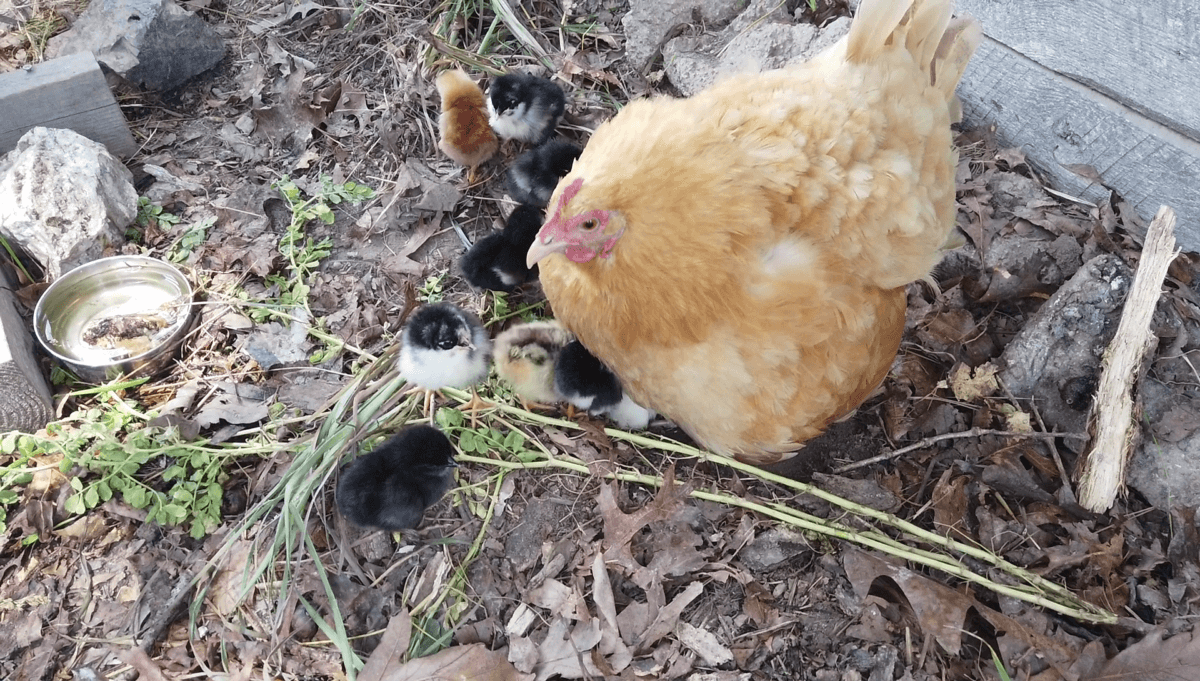

This month is all about raising chickens. There are few other animals so symbolic of the homesteading spirit as the humble barnyard hen. Many of you share your lives with various assemblages of these friendly, fluffy, fowl, and you have some excellent questions about how to make their lives happy and healthy.

Watch The Video

I’ll give you the best tips I’ve got, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t also point you in the direction of our 3-hour course The Beginner’s Guide to Raising Chickens. It’s chock full of information, tips, tricks, and more about transforming from a chicken novice to an experienced and knowledgeable keeper.

Lets get to answering some of your questions!

1. What’s the Best Method for Acquiring Chickens for the First Time? Is It Better to Raise Them Yourself?

There’s a case to be made for starting with chicks, pullets, or full-grown birds. I’ll give you the pros and cons of all three as I see them, then let you be the judge of which fits your lifestyle and budget best.

Chicks

There are several upsides to starting out with chicks. First, depending on the breed, they are pretty “cheep” (pardon the pun). Ordering from a hatchery gives you access to a whole rainbow of breeds that may not be common locally. On the other hand, buying them from a local seller may get you connected with a mentor. I’ve gotten fine chicks from my local feed store as well — just be sure to buy the biggest, brightest looking, and not a scared, lifeless chick in the corner. Chicks are really easy. All they need is a small, clean, warm space with fresh water and good food. And as long as they’re happy, they’re relatively quiet. Chicks are probably the best fit for the absolute beginner because you get to progress alongside them. As they gain abilities and grow, you likewise gain experiences and grow in understanding. So if you’ve never kept livestock before, you could hardly ask for an easier beginning.

There are some downsides to starting out with chicks, however. Probably the most notable one is no matter how carefully they are raised, some of them will die. The first two weeks are the most sensitive time for them, and the period where they are the most vulnerable. Some will be runts, some may fall prey to predators (including your curious dog or cat), and some may fall victim to your inexperience. Your first batch of chicks will train you to care for future years of chicken keeping, so give them and yourself a heaping measure of grace.

Another big downside to chicks is the time it will take for them to reach useful production. If you’re excited about gathering fresh eggs from the coop or roasting your own homegrown meat, you may need to put in a full year’s worth of work before those goals are realized.

A final potential downside to chicks (depending on how you look at it) is that many breeds aren’t sex-linked. With a straight run of chicks, the ratio of male to female is anyone’s guess. If you end up with more males than you have healthy space for — and remember, they’ll start fighting each other upon reaching maturity — you’ll need to have a new home or roasting pan plan for those roosters before they beat each other to a pulp.

Pullets

If you want results a little sooner, pullets may be your ideal starting place. Pullets are hens that are under a year old but are usually close to adult size. They are sometimes referred to as “started.” These birds have made it through the dangerous gateways of early chickhood and are well on their way to being productive, healthy hens. Often, a pullet will start laying the year you get them. They will be more expensive than chicks, but you recoup any extra cost by having fewer, if any, losses to those early chick issues. In my experience, I’ve only ever seen pullets sold directly from breeders or in local, Craigslist-style listings. Shipping a nearly adult bird would be far too traumatic. Your options may be slim since you’re probably restricted to the breeds raised within your driving vicinity. And remember, if you get to pick from a group, look for active, alert birds with bright eyes free of discharge, clear noses, smooth, clean plumage, and smooth legs.

Whether you’re starting out with pullets or mature birds, another big thing to ensure is to have their housing and fencing in place before they come home. Full-grown birds aren’t nearly as easy to contain as chicks. They can fly, they can roam, and they will be scared until they’ve got their bearings. Even if you’re planning to free-range, set up a temporary fence around the coop to help teach your birds where home is, and keep the fences up for at least two weeks to get them acclimated. Also, it may be a benefit to immediately clip the flight feathers of one wing before you set them loose in their new area. Eventually, they will understand where to go, but in the meantime, clipping will give you an advantage in keeping them where they should be.

Hens

A third option for starting out with chickens is to buy full-grown birds. As with pullets, you can usually find adult chickens in many local settings from online listings to fairs to livestock swaps and auctions. The benefit to getting an adult bird is they are immediately ready to join the homestead in a productive way — though the trauma of being transported may set a hen back from laying eggs for a few weeks. You also get the chance to interact with local chicken keepers, which may set you up with a helpful contact or some good tips to put you on the right track. Locally raised chickens are also breeds that do well in your specific climate. It’s a great way to find out which chickens flourish in your weather without having to do the trial-and-error on your own.

The disadvantages may not be as obvious to see initially. Buying adult birds from a farm you aren’t familiar with is a bit of a trust exercise. We always hope that people are truthful, but there’s no way to verify the ages of adult birds that you acquire. You may be getting a bird that is much older than you realize. Also, bringing in birds from other farms is essentially bringing the farm practices of other farms to your property. A hen from a crowded, ill-managed place may be sick or loaded with parasites. Set up a separate area to quarantine and observe a new arrival for a week before she joins the coop, to ensure you don’t have any hidden internal or external hitchhikers. If you do find a problem, you’ll be glad you only need to treat one bird, and not all!

2. What Type of Bedding Is Best if You Want to put It on the Garden Once the Chickens Are Done?

In our modern day, bedding has been made into a product to be bought at the store, but it wasn’t always this way. Bedding used to be sourced from the land where the chickens were raised, and past chicken keepers knew that pretty much any dry, organic material would do. I should clarify that in this case, I’m using the term “organic” as something that’s carbon-based — though you should certainly keep pesticides out of the coop anyway.

So if you have a bit of your own land, bedding should be a no-brainer. Dry autumn leaves, dry grass clippings, pine needles, dry corn husks — pretty much any dry leafy or straw-like material works. The chickens will scratch it up, mix in their droppings, and turn it into fine compost within a year or so. Keep adding it to your coop when needed, and harvest it out in the late winter before it’s time to plant. Spread it on the garden beds at least six weeks before you plan on working them, and you’ll be in good shape. Any extra material can go in the compost until it’s time to shine. Now, with so much freely available material out there, just waiting to be raked up and added to the coop, I can’t give recommendations for what purchasable products compost the best. I haven’t used them and never will.

For those who live in the city, I understand that site-harvestable bedding options are more limited. Buying bales of straw might be the best option for you. It is easy to find, a wonderful winter mulch, and once broken down for a year, it’s a good soil amendment. That said, you have a huge opportunity every fall to gather as much free bedding as you could ever want in dry leaves. Offer to gather them from your neighbors’ yards in the fall, and your chickens and gardens will be well supplied.

3. What’s the Secret to Strong Eggshells?

The producers of bagged feed will tell you their product contains the secret to strong eggshells. But that begs the question … how did chickens survive before we had name brands assuring us of their kibble’s calcium content? How did chickens produce hard eggshells before free-choice tubs of oyster shells were miraculously delivered to them from the far-off ocean? I don’t mean to sound derisive, but I get frustrated when folks new to chicken keeping are given a laundry list of products to be successful. By learning how chickens are designed and function, they can see the ample resources that are naturally available.

So while there are products you can buy to make your chickens lay hard eggshells, I’m not recommending them. Instead, I want you to know the real formula to strong eggshells (and healthy chickens): A diverse, insect and veggie-rich diet plus limestone grit plus access to sunlight equals strong eggshells. Let me break that down further.

Calcium is not only found in oyster shell. It’s naturally available in many forms that are a lot more available, and one of the best methods to get calcium to your hens is to provide a good diet. Vegetable scraps from cabbage, kale, broccoli, turnips, and other leafy greens, are excellent sources of calcium — as are the leafy greens from many wild plants. Give your chickens as many greens as they want from your gardens and fields, and you’re well on the way to their good health. Crushed eggshells are also a great addition to the diet. Just smash and give them back to the birds. And another source of calcium? The insects your birds go crazy for. Earthworms, pill bugs, and soldier-fly larvae are a few of the calcium-rich invertebrates that should be part of every chicken’s diet (yet another nail in the coffin that a vegetarian diet is best for chickens).

Another easily accessible source of calcium is limestone grit. It’s available widely, and not only at the feed store. We order fine limestone gravel and “fines” from our local quarry and get them delivered to our homestead. The gravel pile helps with construction projects, but it also doubles as an excellent grit for all of our birds.

Finally, chickens have to have vitamins and vitamin D in particular, to process all that calcium. Now, I know there are vitamin D supplements, but if your birds can’t reach the free light from the sun, maybe your chicken situation needs some necessary naturalization.

4. What Breeds Are Best for Free-Ranging?

There are several factors to keep in mind when selecting a breed for your free-ranging flock. I’ll do my best to lay them out for your consideration.

A free-range bird must have a good foraging instinct

They’ll only be able to get the most from their freedom if they actually want it. Industrial meat birds such as the Cornish Cross, for example, don’t generally have enough desire or instinct for finding their own food. They’d rather you bring it to them. In contrast, most heritage breeds are decent at foraging, and some, such as the Buckeye, Welsummer, or the Hamburg, are exceptional at it.

A free-range bird should be wary and flighty

Folks looking for backyard chickens often desire friendly, docile birds, but all that personality often comes at the expense of the bird’s good sense and judgment. A bird that’s still aware of its surroundings and looking around at all times in apparent paranoia is the bird that will more likely escape a predator. Wary fliers include the Leghorn, the Sumatra, the Old English Game, and the Faiyumi.

Birds with dark or patterned plumage often fare better than their white counterparts

That is because they blend in with the foliage so much more easily. There are brown Leghorns, for example, that are particularly recommended for free-ranging. Game-type birds usually have coloration that is close to their wild Red Jungle Fowl counterparts, making them ideal camouflage artists.

Keep those three factors in mind as you scope out the dozens of chicken breeds, and make sure you also select a breed that fits your climate. If you’re interested, check out our Chicken Breeds Database for a look at 50+ breeds — maybe the one you’re looking for is described there?

5. What Breeds Do You Raise?

I personally raise an ever-changing box of chocolates. I’m trying to learn how to selectively breed birds for traits that suit my own homestead purposes, and hoping to eventually refine them into a new landrace or breed that is a custom-fit for here. That’s how all our breeds came to be. After all, early chicken keepers started mixing and matching and refining specific features until they found something good.

At the moment, my flock is comprised of Speckled Sussexes, Orpingtons, Australorps, Wyandottes, Rhode Island Reds, Easter Eggers, Leghorns, and an increasing number of their mixed descendants. My goals are for good foraging skills, excellent broodiness and mothering skills, heat tolerance, and parasite resistance. It’ll take a while, but it’s a fun experiment. I’m excited to see what interesting feathering patterns and personalities emerge from the mix.

I hope those answers can get you pointed in the right direction as you make your own decisions and decide what is best for your birds.

If you want your question answered next, ask away in the comments, or pose them on our Insteading Community page. We’ll round up some good ones and answer soon.

Leave a Reply