Homesteaders have a lot to consider and accomplish when physical and mental self-sufficiency is the goal. We store up pantries full of homegrown food and rest in homes heated by wood we split ourselves. We spend a lot of time researching natural remedies for chicken diseases or drought-tolerant varieties of squash. We talk endlessly of our plans for rotational grazing or hugelkultur mounds.

But among all the articles, books, and magazines dedicated to our chosen lifestyles, I have found a surprisingly small amount of time and energy dedicated to the mental aspects of self-sufficiency.

Some of us have learned the hard way that you can be prepared physically with tools, plans, and animals at hand, but if your mind isn’t equally prepared, your homesteading efforts will always be frustrated in some degree. Frustration, gossip, conflicting opinions, or the whispering voice of doubt can often hinder us a hundred times more effectively than a downed tree or a dead truck battery. Many of us did not grow up homesteading, so transitioning to a new way of life can come with a hefty dose of accompanying mental transition.

That said, I hope that the following ideas and concepts can offer encouragement and food for thought as you face the trials that we homesteaders go through on our path to self-sufficiency.

Ability to Act With a Low Threshold

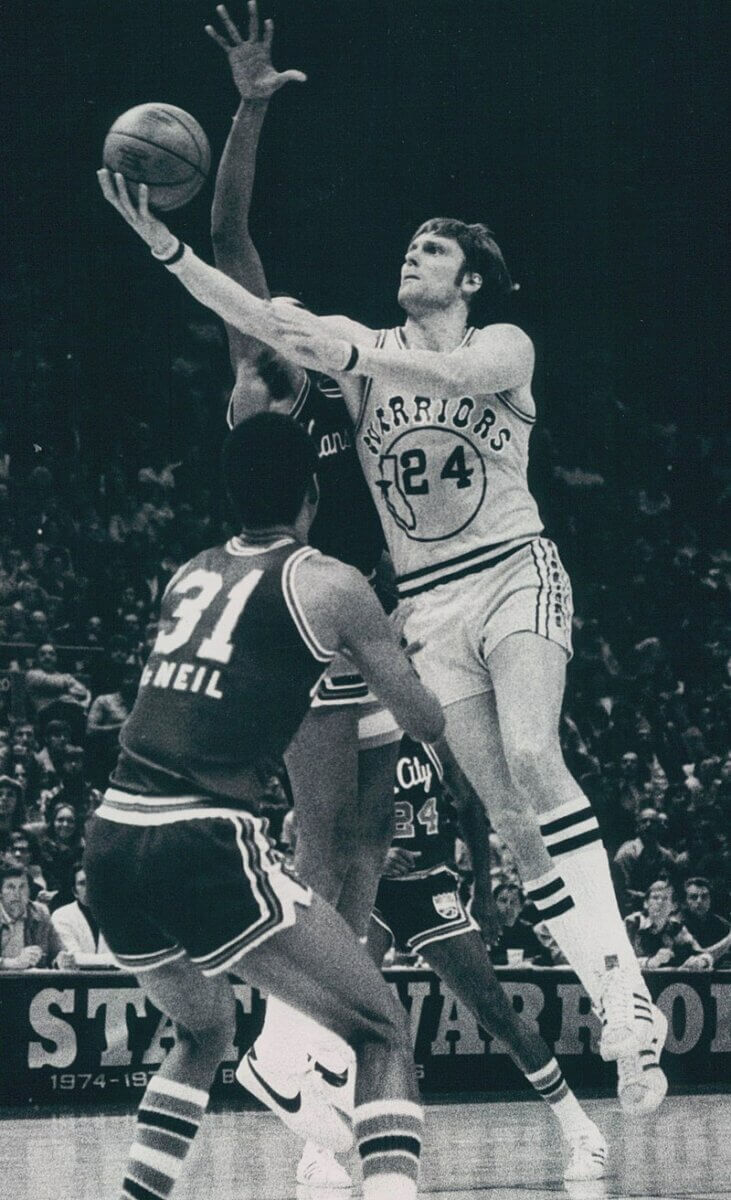

This first concept requires some backstory about a basketball player named Rick Barry. Barry is known as the greatest foul shooter of all time with a record of missing only 9 or 10 shots a season (for comparison, LeBron James misses around 150 free throws a season). There’s one huge difference between Barry and all the rest of the so-called basketball greats. Instead of perfecting a poster-perfect overhead throw, he perfected the not-so-photogenic underhanded throw, colloquially termed the “granny shot.”

An underhand throw has an incredibly high rate of success, which is why Rick Barry was had such outstanding statistics. He tried to share his methods with other players to help improve their performance, but to no avail. You’ll never see anyone use a granny shot in televised games for the simple fact that, as a society, we’ve decided it looks too dorky. It doesn’t matter that, if practiced, it nearly guarantees a basket during a high-stakes free throw. As Shaquille O’Neal put it when Barry suggested he try his technique: “I’d rather shoot zero than shoot underhanded.”

Rick Barry has what is known as a low threshold, a concept created by sociologist Mark Granovetter. As Malcolm Gladwell said in his podcast on this topic: “A low threshold [can lead] to brave or innovative behavior. If you have a threshold of zero, you’re someone who doesn’t need the support or approval, or the company of others to do what you think is right.”

Comparatively, those other pro players have a high threshold. They care very much what other people think and would never do anything to disrupt their public image unless others did, too. Wilt Chamberlain, for example, had a record-breaking game where he tried the underhand technique and made 28 free throws. Though the idea obviously worked, he never tried it again. He ended up with a dismal 40% rate for his free throws.

I believe that, in order to be successful and content, a self-sufficiency-seeking homesteader must have a low threshold. If you have made an excellent DIY composting toilet system that works perfectly in your cabin, you can’t care that your family doesn’t approve of a home without flush toilets, or that no one you know has one. If you quit the well-paying job you hated so you can live in comparative poverty on your happy homestead, you can’t care what your coworkers are saying about you. If you are homeschooling your kids because you know what’s right for them intellectually, morally, and spiritually, who cares what the neighbors think when they see your brood doing outdoor science at 10 a.m. You don’t need someone to go ahead of you to test the waters and tell you how to follow. You blaze a bold, experimental, otherwise unknown trail.

Ability to Patchwork an Answer

I am old enough to remember a world before online search engines or those creepy digital assistants that quietly monitor the room for your inquiries. Back then, we went to the library to find a specific answer to a question.

I am young enough, however, to have watched the transition from glossary searching to Google searching. When I was a teacher, my students had no idea what the index at the back of a textbook was for. When I told them how to use it, one student slumped in his chair, whining “That’s so much work!” He then whipped out his school-issued tablet, laid it on top of the ignored book, and brought up the first result that Google handed him

And that was back in 2014. The ability to comb through information, synthesize it, and come up with an answer that suits your personal inquiry has never been in more dire straits than it is now. For the adults that my students became, if the exact answer doesn’t show up in the first two websites listed in an online search, I guarantee most of them conclude the question is impossible to answer.

Homesteading, is not a standard-issue life experience. Every homestead has a unique set of residents, climates, animals, plants, and philosophies. Though people may frantically search online, magazines and books can’t possibly give a one-size-fits-all answer for your specific situation.

In order to be a successful homesteader in the long run, I believe it is imperative that you learn how to find answers, even if those answer aren’t printed plainly in front of your face. Sometimes, you’ll need to comb through stacks of old resources to glean enough bits of information and Frankenstein together your own solution. Sometimes you’ll need to merge ancient techniques with modern ones. Sometimes you’ll have to find answers by simply trying and failing until you finally try, and it doesn’t fail. It sounds easy on paper, but many people feel so intimidated approaching a task without a step-by-step guide that they won’t attempt it at all. A successful homesteader can’t let a lack of hand-holding stop them from innovating. Sometimes, our very success depends on it.

Ability to Know Thyself

If you’re familiar with this ancient Greek aphorism, you know it has been enigmatically used to explore various philosophical avenues. For this article, I intend to use it psychologically, as a foil for the concept sometimes called “personal intelligence.” That is, if you are able to understand how your mind is wired, then you are also aware of your predisposed weaknesses and can, as University of Connecticut Professor Mitchell Green put it, “Acknowledge your limitations.”

As I’ve found, thinking like a self-reliant homesteader requires some resistance to our inherited lifestyle conditioning. All of us were born into a certain way of living that is influenced by our social class, our race, our culture, and the area where we grew up. Whether we were in the keeping-up-with-the-Joneses suburbia, the Grandaddy-did-it-this-way country, or the modernization-and-convenience-at-all-costs city. Knowing where you came from — and the conditioned limitations it taught you — can help you know where the mental battles will be as you hack out a new way of life.

Consider the (often true) generalizations. Rural-born folks can be resistant to change, which makes innovation and the merging of old and new knowledge a real struggle — even if that’s exactly the answer your homestead needs to become more self-reliant. Suburban folks often do something only if the experts or someone in authority gives them permission, which can impede formulating your own plans and thinking for yourself. Formerly urban folks may be hobbled by the physically rustic nature of self-sufficiency; the grime, manure, sweat, blood, and lack of empathy from the next-door neighbors. If you know these pitfalls are ahead, maybe you can prepare yourself to confront … and triumph over them.

As you may notice, I’m really saying the same thing three ways. The mental framework of the self-sufficient must include an independence, innovation, and awareness of themselves. A long time ago, I imagine those old-time homesteaders and pioneers didn’t have to explain this concept with a drawn out, sociological or psychological analysis, however. They just called it grit.

Thank you for discussing this subject!