There are several plants that have become all but invisible due to their sheer ubiquity and the fact they can grow in less-than-desirable places.

Watch the video:

Dock is one of those plants – a colonizer of empty lots, a squatter in industrial gravel piles, roadside inhabitant, and pasture weed.

For years, its subliminal association with unpleasant places like dirty alleyways or dumpsters kept me from trying it. But when I moved to my homestead, I found myself surrounded by lush, leafy greens as far as the eye could see. Dock was there, patiently waiting for me to shed my industrial associations and finally see it for what it is: A tough-as-nails, generous plant that offers mild-tasting leaves (and more) during multiple harvesting seasons.

Sorry for judging you, buddy.

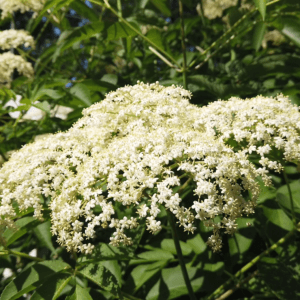

Identifying Dock

In this article, I’ll be focusing solely on curly dock (Rumex crispus) as it’s the species I’m surrounded by and generally, the most widely abundant in the United States.

There are several estimable species of dock to forage, however, including field dock (R. pseudonatronatus), narrowleaf dock (R. stenophyllus), western dock (R. occidentalis), and patience dock (R. patientia). All docks are edible, but you’ll find that some are tastier than others. Patience dock is apparently the most delicious of them all. I have yet to find one myself to verify this claim, but I believe it.

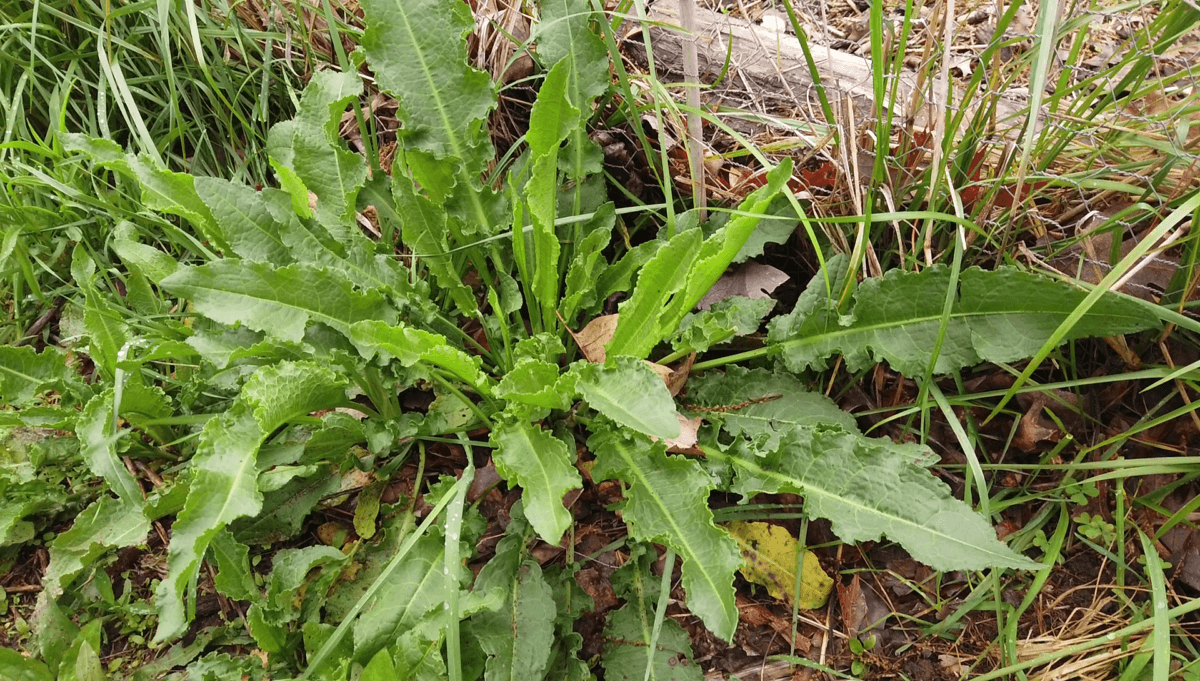

Curly dock, like all docks, is a perennial with a yellow, deep-growing taproot. It begins growing as a basal rosette with elongated, lance-shaped leaves. The leaves can be quite large — sometimes more than a foot long. They are distinctively veined, with a prominent midrib that’s usually a slightly different color than the leaf tissue. The margins of the leaves are wavy. They remind me, and many other foragers, of lasagna noodles. When picked young, broken leaves will leave a slimy feeling on your hands. There’s nothing to worry about if you feel slime — in fact, it’s another confirming sign that you’ve got the right plant.

Dock is usually found in sunny, moist, and somewhat disturbed ground. That’s why it’s so ubiquitous with construction sites or agricultural ground. On my land, dock plants are most prominent around areas I frequent: the chicken coop, all over the gardens, and footpaths. They get more sparse the further they are from human activity. From coast to coast, you’ll likely find a dock that is either native or introduced, so finding it shouldn’t be a problem.

Dock takes several forms throughout the growing year, and knowing them all will give you something to harvest from spring to fall.

In the spring, dock will form a rosette of leaves, springing from a central point. These will be some of your biggest handfuls to collect, and the most tender greens from this plant.

In late spring, dock will start to bolt, sending up a flower stalk. Leaves will still form along the stalk, but they will be narrower and far smaller. At this point, the leaves around the base may have grown over a foot long.

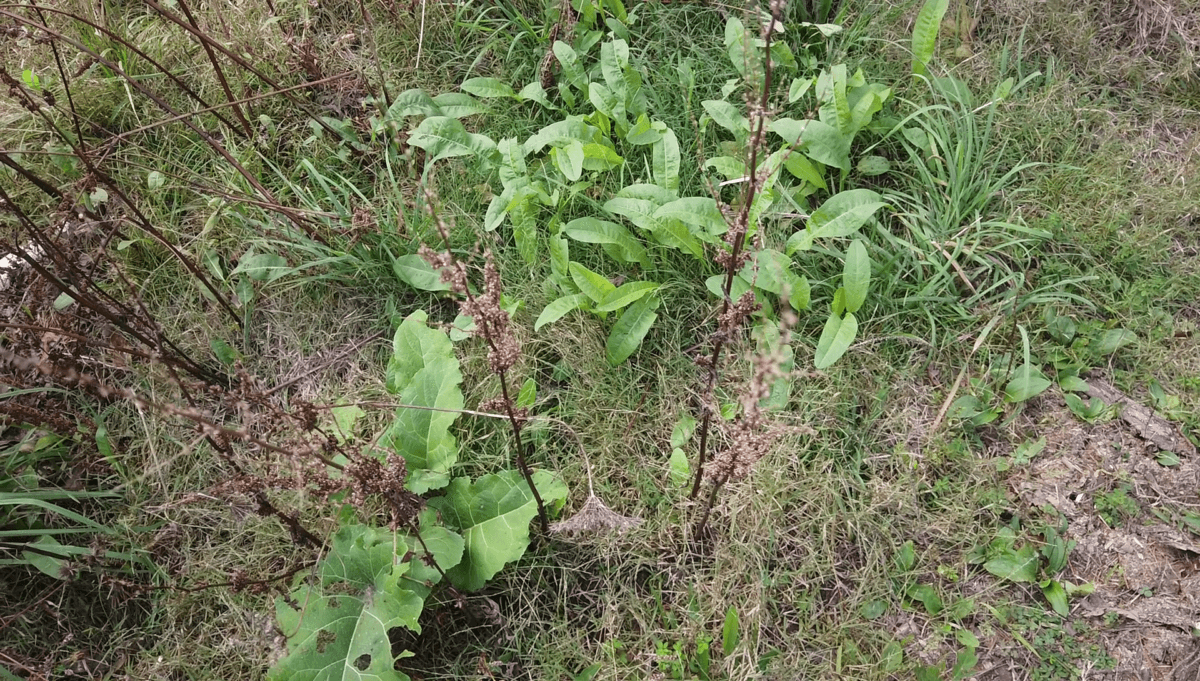

The flower stalk will change to a loaded, coffee-brown seed head during the hottest parts of summer. After the abundant, somewhat pyramidal seeds are fully ripe, the plant starts to die back and wither.

But we’re not done yet. In the fall, from beneath the dried, dead stems, dock will send out a bonus round of tasty leaves for a last hurrah. Though they’re smaller than the abundance offered early in the year, they still give the forager one last gift before the frost sends much of the greenery into hiding.

Dock Look-Alikes

Probably the most easily confused dock look-alike is wild horseradish (Armoracia rusticana). It’s unlikely you’ll find it, however. The plant is relatively rare, and even if you do somehow make the mix-up, you’ll still be harvesting an edible green (just one with a very different kick of flavor).

Another potential mix-up for the forager is attempting to harvest prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum) or burdock (Arctium lappa). Though both have “dock” in the name, they’re not part of the same family as the true docks. They are from the Asteraceae/Compositae family. Prairie dock, with its leather tough, sandpaper-like leaves, will not seem edible once you handle it — which is helpful. And there’s nothing poisonous about burdock. The young leaves are edible, the older leaves are debatably palatable, and the root is a valued vegetable.

Harvesting Dock

Leaves

Dock leaves are a bit different in shape and texture through the growing season, but edible at all times. In the spring, the unfurling new leaves are choice pickings. The most tender leaves will be the ones that still have crimp marks running lengthwise along the surface. They are usually the leaves many foraging books tell you to pick, and some folks like to eat them raw.

But I always cook dock, and because of that, I would recommend that you not skip the bigger leaves. They may look coarse and tough, and maybe they’re a bit bitter in a salad, but I have found they cook up as nicely as the smaller ones with no trace of bitterness. The stems can be hard to chew, so I usually harvest these by stripping the leaf tissue off the center vein. Dock is so prolific, hardy, and common that this rough handling won’t harm the plants.

At the peak of the season, you can collect a huge bowlful of dock leaves in record time. In terms of food output, I’ve found that dock is second only to pokeweed in the amount you can collect and feast on through the spring. What a gift!

Flower Stalk

When still tender and not yet blooming, the bolted stalks of dock are also a good vegetable. Samuel Thayer recommends stripping the leaves and peeling the tough outer layer, but I happily chop it, leaves and all, and include it in my stir-fried greens.

Seeds

In my personal experience, dock seeds are just … terrible. I’ve tried them raw, dried, and roasted, and I find them mouth-puckeringly bad — but that is merely my own experience. Maybe this is some sort of genetic thing where certain people taste things that others don’t. Because the truth is, many folks really like dock seeds. Ashley from Practical Self Reliance actually prefers them to dock leaves (saying that the leaves are near unpalatable) which I find surprising (and fascinating).

So this is an opportunity for you to find out for yourself. Don’t skip over dock seeds merely because I said I don’t like them. They’re abundant and incredibly easy to harvest. Run your hand down a brown-dry seed head and they’ll readily fall in your hand. They look like tiny buckwheat seeds with a papery ring around them, which is fitting since dock are in the buckwheat family. Perhaps there’s a way to prepare them that makes them worthwhile. I’d be curious to hear what experimenters have to say in the comments below.

Preparing Dock

Dock can be handled as you would any green. It doesn’t need to be parboiled like poke, so when you bring it in the kitchen, all it needs is a rinse before you transform it into whatever you fancy.

The first time you cook dock, you’ll likely notice that it undergoes a color change once heated. The bright, verdant green quickly dulls to a more olive-drab hue. For those who value the nutrition and taste of dock more than its appearance, this isn’t a problem. But for the forager who has to cater to pickier tastes, it may be best to cook dock with some other bright-colored ingredient to jazz it up. I often mix dock with bright violet greens because they are abundant at the same time, and violets tend to stay green when cooked.

Now, on a typical day, I usually gather a big pile of dock greens and tender stalks and sautee them with onions, garlic, and salt. A simple preparation like this makes it easy to eat your greens nearly every day.

But if you’re looking to try dock in some different ways, I humbly recommend you check out our earlier video/article on some creative and tasty ways to use greens. Dock fits perfectly with any of the recipes I shared there.

So though I once shuffled dock into the “trash weed” category of my mind, I’m now glad that moving to my homestead allowed me to see the folly of my ways. I am thankful to have met this incredibly generous, multiseason plant, and it has been a part of my menus ever since. I hope that you can get acquainted with it yourself, and enjoy the nutritious deliciousness waiting for you at the side of the barn, the garden, and the path along the way.

Excellent article. I wonder if it is tricky to harvest on roadsides or many disturbed areas due to potential contaminants.

Can I eat the green colored flowers forming on the stems of the broadleaf plant?