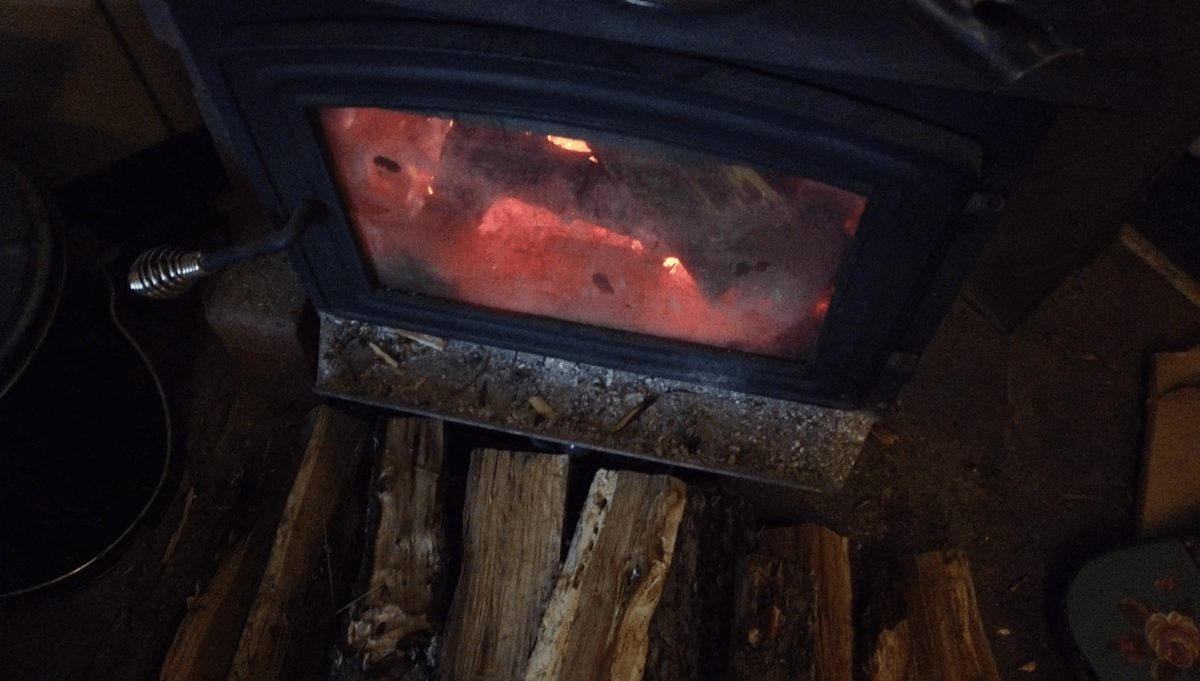

Of all the ways that we heat our homes, none goes as far back in time as wood.

Coal, electricity, and natural gas are all recent newcomers on the block in comparison to wood. Something about the light of a wood fire has always held the hearts of man – long can you stare into the wisps of flame in a contented silence of contemplation.

Let’s take a look into the world of firewood and learn about this wonderful material.

The Two Main Categories of Wood

When talking about wood, people usually split it in two main categories: softwood and hardwood. These categories are certainly less than perfect, but they are helpful to some extent, and as they are the main way the majority of people delineate wood, they are the terms that I will use in this article.

First of all, know that these two categories are not completely accurate in their naming. There are some hardwoods that are soft, and there are some softwoods that are hard. Woods like cottonwood and balsa are both technically hardwoods, but they are also notably soft in nature. On the flip side, some softwoods, like shortleaf pine and other species of the southern yellow pines, are quite hard. Now that you know these two categories are something of misnomers, let’s move into each group’s general traits.

Softwood

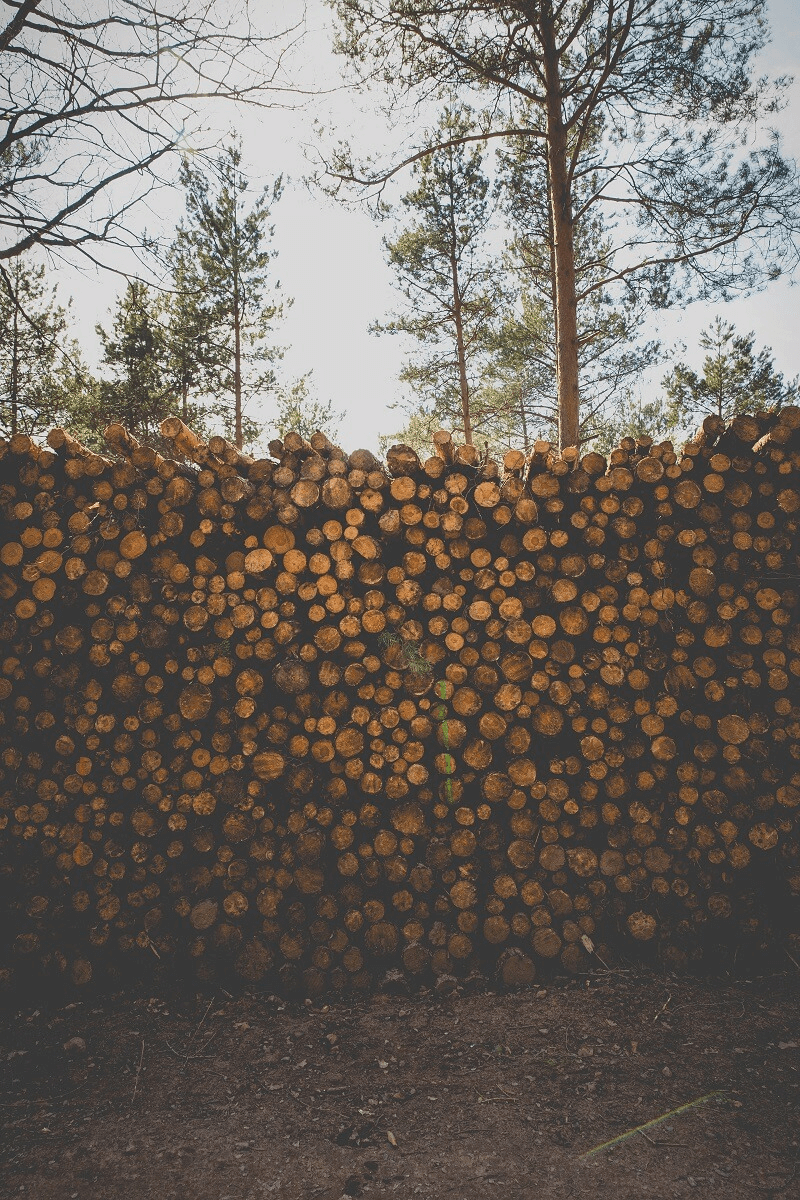

Softwoods are the conifers. Scientifically speaking, they are known as gymnosperms. This Greek-based word means “naked seed” and has to do with the fact their seeds are not contained within a fruit. Instead, they typically have cones to hold the seeds until they are ready to be released. These trees generally hold on to their leaves (usually referred to as needles) even during winter which gives them their other moniker – evergreen trees. Both the oldest trees, like the bristlecone pines, and the largest trees, like the redwoods and sequoias of the western United States, are gymnosperms. Softwoods are found in more extreme climates than their hardwood cousins. The trees that can grow the farthest north, and those that can grow the highest up on mountains, are conifers. Obviously, softwood does not mean weak wood.

As for the wood of these trees, it is usually less dense than an average hardwood. This means that if you have two pieces of split wood of the same size, one from a softwood and one from a hardwood, the hardwood would feel heavier. Due to its high strength to weight ratio, softwoods are the go-to choice for the construction industry. If you go to the store and grab a two-by-four, it will be a softwood. In fact, the majority of lumber sold in the world is some sort of spruce, pine, or fir – all of which are softwoods.

The final note on softwood trees is that they tend to grow faster than hardwood trees. Their (relatively) quick growth is what makes them less dense. It is also what makes them a good choice for the building industry as a forest can be replanted and grown to a usable size in a much shorter time than would be required for a hardwood forest.

Hardwood

Hardwoods are your deciduous trees – which means they lose their leaves at the end of every growing season in the temperate regions of the world. Some parts of the world, like Ohio and Pennsylvania in the United States, are known for the beautiful colors of the autumn leaves that change color before they fall from the tree. From the bright glowing yellow of black maples to the brilliant red of red maples, hardwood puts on its best display for a brief time every fall.

Hardwoods are known as fruit-bearing trees and are given a scientific name from the Greek to reflect it. This name is angiosperm which can be translated as “receptacle seed.” Unlike the conifers, these trees have seeds enclosed within a fruit of some sort. It can be a juicy fruit, like those of an orange or apple tree, or a dry fruit, like a hickory or oak.

As already mentioned in the section on softwoods, hardwoods are generally denser than softwoods. This density makes hardwood not quite as well suited for general construction but is preferred over softwood for things like furniture, tool handles, and finish carpentry.

Measurements for Amounts of Wood

When you purchase wood, you will come across a few terms that are pretty much specific to the world of firewood. These terms are cord, face cord, and rick.

Cord

A cord of wood is a stack of split wood measuring 8 feet long, 4 feet high, and 4 feet deep. Generally, a cord will be made up of split wood that has been cut to be 16 inches long. Therefore, the wood that makes up a cord is usually stacked in three rows (16 + 16 + 16 inches = 48 inches or 4 feet) right in front of the other.

Rick

A rick is one of the three stacks of wood in a cord. This makes a rick 8 feet long, 4 feet high, and 16 inches wide. Some people will cut wood to some size other than 16 inches (18 inches is common) and still call it a rick. You can always ask before you buy.

*Face cord is another term for a rick.

As mentioned, the most common length for individual pieces of wood is 16 inches. This is because that length will fit in most wood stoves purchased in the United States. If you are cutting your own firewood, you can cut it to whatever length is convenient for you to fit in your specific wood stove.

Choosing Firewood for Burning

And now we get to the age-old question: What is the best type of wood for burning? There are generally two main camps when answering this question. On the one side, you have the people who will argue about specific types of wood and their BTU outputs and come to the conclusion that some well-seasoned hardwood like oak, hickory, or ash is the best. On the other side of the spectrum, you have the pragmatist who states without equivocation that the best wood is whatever wood happens to be stacked outside the house ready to use.

I would say there is merit to both arguments. In any case, let’s talk about some of the basics so you can at least understand this argument if you ever take part.

Understanding BTUs

In order to understand why people argue about the best wood for firewood, you first need to understand the basics of heat output.

Heat output is measured in a unit called BTU, which stands for British thermal unit. It is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by 1 degree Fahrenheit (measured when the water is at a temperature of 39 degrees Fahrenheit). So, if a material has a heat output of 50 BTUs, it is able to raise the temperature of one pound of water by 50 degrees or 50 pounds of water by 1 degree. And for those of you who were wondering, this unit is only used in the United States. The rest of the world uses joules (J) or kilojoules (kJ).

So why the argument? Well, different types of wood contain different amount of stored energy and will therefore release different levels of heat. Thankfully, you do not need your own lab to figure out the thermal output for various types of wood. This information is printed in almost every book or website on the subject. Here is a sampling of various woods and their thermal output.

| Type of Wood | BTU Output (millions BTU per cord) |

| Shagbark Hickory | 27.7 |

| Apple | 25.8 |

| White Oak | 24.0 |

| Red Elm | 21.6 |

| Cottonwood | 13.5 |

| Norway Pine | 17.1 |

| Eastern White Pine | 14.3 |

| Shortleaf Pine | 22.0 |

| Black Spruce | 15.9 |

It should be noted that the above values are averages and the actual output will vary considerably. The thermal output will be much lower in wet green wood, and much higher in well-seasoned wood of the same species. I have also found much difference between individual trees of the same species. In any case, these charts are still good for comparing the average trees of different species.

On any of these charts, you will find that the denser woods are king when it comes to BTU output. This generally means hardwoods as they are slower growing and therefore denser. However, there are exceptions to this. Cottonwood, a fast-growing hardwood, has a low BTU rating while shortleaf pine, a southern softwood, has a very high rating.

Ease of Splitting

If you are splitting your own wood by hand, then how easy it is to split could be a big factor in what you choose for firewood. You will quickly find there are some woods that are easy to split and some woods that are very, very difficult to split. Elm is notoriously difficult to split, and that explains why it was once the favored wood for the hubs of wagon wheels. In my experience, the only wood harder to split than elm was black tupelo. I was unable to split it even with wedges, and gave up. Others say that sweetgum and cottonwood are almost impossible to split by hand as well.

As far as easy-to-split wood, most straight-grained hardwoods won’t give you too much of a headache. Hickories, oaks, and ashes are fairly easy to split. I split quite a bit of shortleaf pine which is easy, as well.

Formation of Creosote

Creosote is a tarry deposit that forms in your chimney when burning wood. If not taken care of, it can ignite and cause a dangerous chimney fire that can burn down a home. I mention this because some types of wood (generally softwoods) are known to create creosote deposits faster than others. Make sure that whatever wood you use in your stove is well-seasoned, as this will reduce creosote formation. Also be sure to clean out your chimney every year before the burning season to keep it free of buildup.

Availability

The final consideration in choosing which wood to burn is probably the most fundamental and important: What can you actually acquire? What good is knowing that Osage orange has the highest heat output (of the woods in the United States) if you can’t get it? What if the only wood that grows in your area is a type of pine with a rather low BTU rating? Well, then none of the above arguments matter. In the end, you are going to burn what you can get your hands on.

If you have a choice, then good for you. Use the above information and other easily-obtainable charts to pick out the perfect wood for use in your home.

Seasoning Wood

Before using wood in your stove, it will generally need to be seasoned. Seasoned wood is wood that has been allowed to dry out over the course of many months or up to a year or two.

The length of time required varies greatly between types of wood. Some pines can be cut in the late winter or early spring and be ready for burning by the next fall and winter, while some of the denser hardwoods won’t burn optimally until the following winter after that. Seasoning wood raises the BTU output of the wood (since the wood doesn’t need to waste thermal energy on the water in the wood) and lowers the amount of creosote that will form in the chimney.

And I will tell you now that if you try to burn wood that is unseasoned, you are going to have a real hard time getting that fire started and going. It is frustrating to keep a fire going with green wood. In order to get it to burn, you will need to have a few pieces of dry wood in there with it or a really hot fire already going. Trust me, it is a hassle and not recommended.

Final Thoughts

There you have it. Hopefully, you now have a basic understanding of firewood and the terms used when discussing it. Wood is a wonderful resource and a completely renewable material. With proper management, you can grow all the wood you need on your acreage for as long as you, your children, and your grandchildren live there.

Is it necessary to split smaller pieces of wood, say up to 6″ in diameter?

It should be mentioned that any BTU chart is based on seasoned wood. Unseasoned or greenwood reduces the BTU output sometimes as much as by 1/2. This is the chart we use:

https://worldforestindustries.com/forest-biofuel/firewood/firewood-btu-ratings/

I burn lodgepole pine.

I have a couple white oak and shag hickory which have been “standing dead” for 2-3 yrs…can these be considered as already seasoned, hence, shortly after I drop them, and cut & split, I can immediately start utilizing them for my wood burning stove?

(no need to age).

Pls advise