Tea is a simple infusion of plant material in hot water, yet somehow, it’s a lot more than that.

It can be culture, conversation, or comfort. You can spend your money on tea and tea paraphernalia, if you want. But if you don’t, you can also get yourself a flavorful cuppa for the price of an afternoon stroll. There are wild plants everywhere that can offer something to brew.

For folks looking to cut down on their caffeine consumption, and the amount of garbage they generate with their daily cup, or who just want to enjoy the can’t-find-it-at-any-store flavor of their own land, wild teas are a fascinating world to explore. The variety of plants that can be steeped and brewed into pleasant and healing drinks seems nearly endless, and I hope I can provide you with some easy-to-identify and easy-to-find “weeds” that will live happily on your tea shelf.

This article is meant as a launching point for exploring all these plants, and it won’t give you a complete means of identification if you have never foraged for them. If you find an intriguing new species in this list, take the scientific name along with you and do more research to be sure you identify it correctly in the field.

Furthermore, this is an incomplete list, and I hope that statement comes as exciting news. The plants available to throw in a teapot are incredibly diverse.

12 Wild Tea Leaves to Look For

These 12 are the plants I most commonly reach for, but only because they’re easy to find in the Ozarks. There are guaranteed to be dozens more to discover in your area.

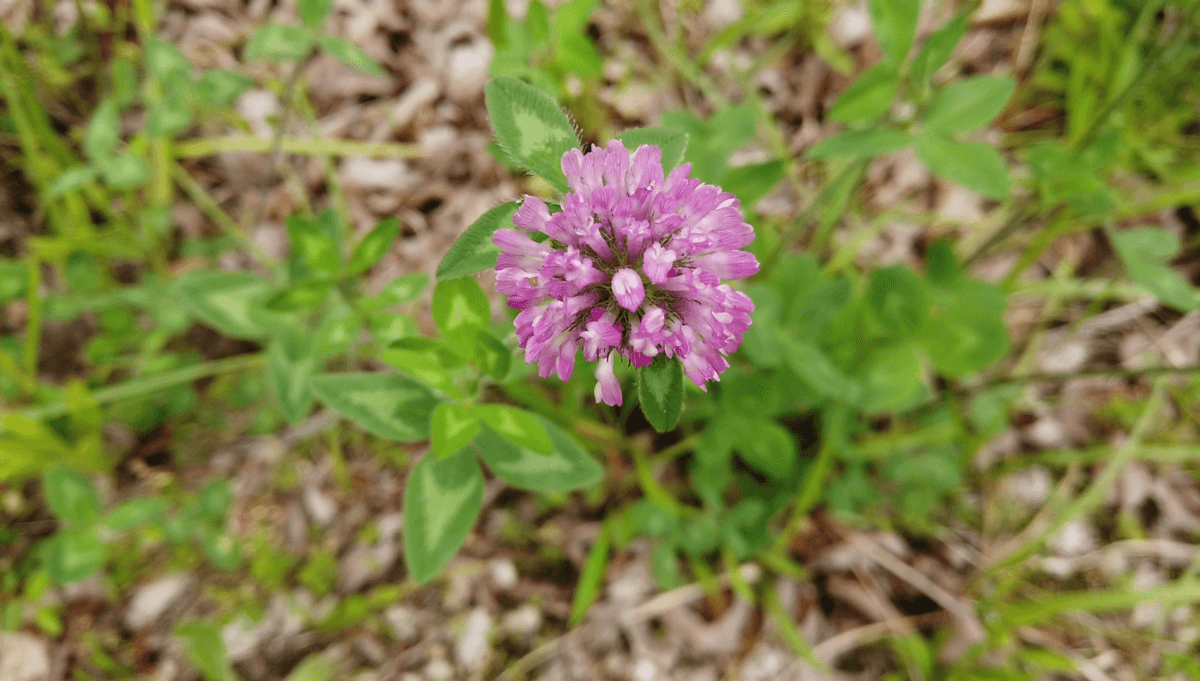

Red Clover Flower and Leaf (Trifolium pratense)

I confess red clover is one of my favorite wild teas, so that’s why I had to make sure it started this list. The bright, pinky-red blossoms and surrounding leaves below it can be harvested by the handful, used fresh or dried, and preserved to make a sweetly sustaining beverage that tastes like early summer captured in a cup. White clover (Trifolium repens) can also be used, but I find its white blossoms aren’t quite as sweet.

Bear in mind that red clover is rich in minerals, which means it can be contaminated with heavy metals if you harvest it from a polluted site. Check out our earlier article on how to forage safely if you’re interested, and be sure to always harvest any wild tea from nontoxic land that hasn’t been sprayed.

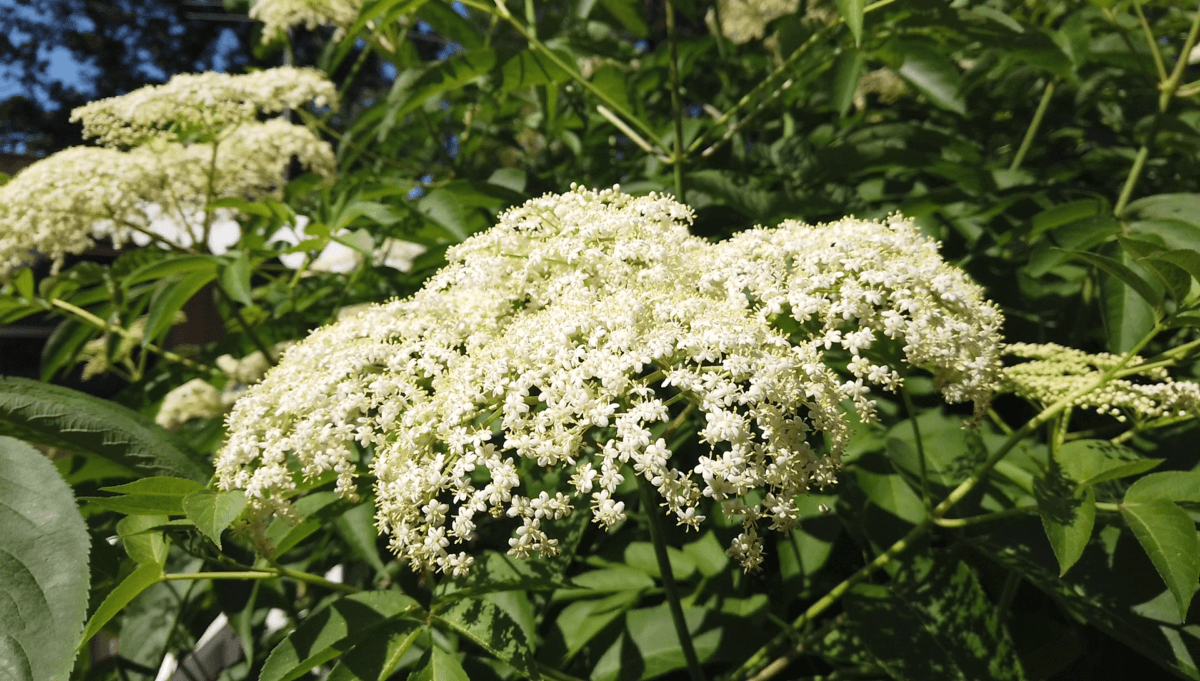

Elderflower (Sambucus nigra)

I would add elderflowers to a cup of tea if only for their poetic presence starring the top of a steaming cup, but they have a delightful flavor as well. Honey-sweet and floral, they make a tea that is delicate in color and flavor. Both cold and hot infusions work well. I particularly like making sun tea out of lemon balm and elder flower.

When harvesting elderflower, I recommend shaking blossoms free from the umbels rather than plucking them. Granted, you’ll get a few ants and spiders along for the ride, but you’ll end up harvesting the pollinated flower petals, leaving the fertilized, embryonic berries for a second harvest a few months later.

Monarda Leaf and Flower (Monarda spp.)

There are several species of tasty plants in this genus, and all of them are excellent for tea either fresh or dried. In the early spring, spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata), Oswego tea (Monarda didyma), eastern beebalm (Monarda bradburiana), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) and their cousins, send up their aromatic paired leaves. A few weeks later, they’ll throw out beautiful, messy-daisy heads, to the frenzied delight of the bumblebees and butterflies.

Both the leaves and flowers are excellent for tea, but I always recommend harvesting only a third of any given plant. These perennials are food for lots of other creatures, and the sight of them in a field is worth prolonging. In the mug, Monarda relatives are aromatic and warming with spicy notes of oregano and mint.

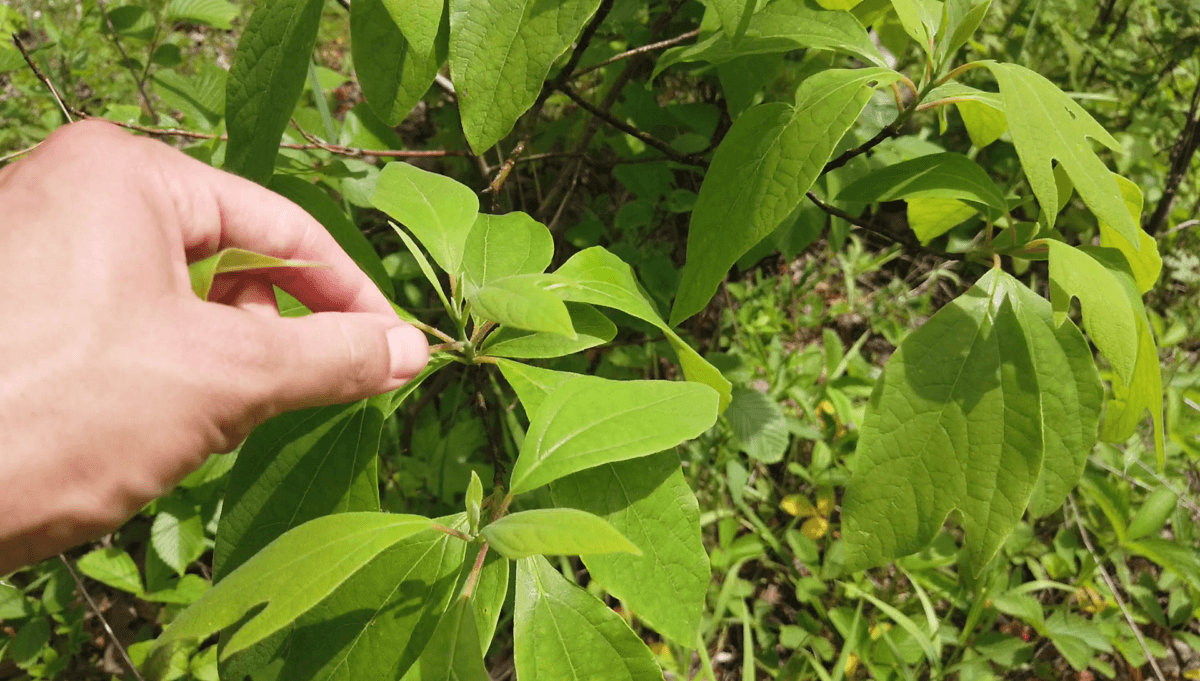

Sassafras Leaf and Root (Sassafras albidum)

Sassafras has gotten a bad rap as a dangerous plant due to some FDA studies on the carcinogenic properties of safrole, a compound found in the roots. Even though the studies were done with concentrated amounts of pure safrole fed to rats rather than the complex brew created by brewing the whole roots into tea, the studies inspired fear. Folks heard “sassafras causes cancer” rather than “artificial preparations of pure safrole administered over a long period of time can hurt a rat” and have feared it ever since.

Seeing that neither you nor I are a rat, and the traditional preparation of whole sassafras root is not a concentrated pure isolate of safrole, I suggest that these cautions have been overblown. I instead encourage you to enjoy sassafras tea any time you’d like just as indigenous people, pioneers, and mountain folk have for hundreds of years. I have well-known foragers who back me up on that assertion, so you don’t have to take my word for it.

This potently aromatic tree offers three different options for your brewing pleasure. First, there’s the spring leaf buds and twigs. Harvest these lightly, as they are meant to become leaves in the later spring, and plucking too many will harm the tree. Second, the leaves themselves. Sassafras leaves lack safrole, so if you’re still worried about those studies despite my efforts, you can harvest them without worry. You can even snack on the newly emerged, tender leaves if you want. They taste unexpectedly like a certain loopy, fruity breakfast cereal.

Finally, tea can be brewed from the sassafras roots. You’ll have to kill a tree in order to gain this tea ingredient, so be sure to choose your victim thoughtfully. Usually, you can find a stand of several small trees clumped together and thin one out. After scrubbing the sweet, spicy roots, chop them in chunks and boil them in water for several minutes to extract a rich, root beer-like tea. The traditional preparation includes boiling (not steeping) the roots. It gives the best flavor, and there’s wisdom in it: Safrole isn’t heat-stable.

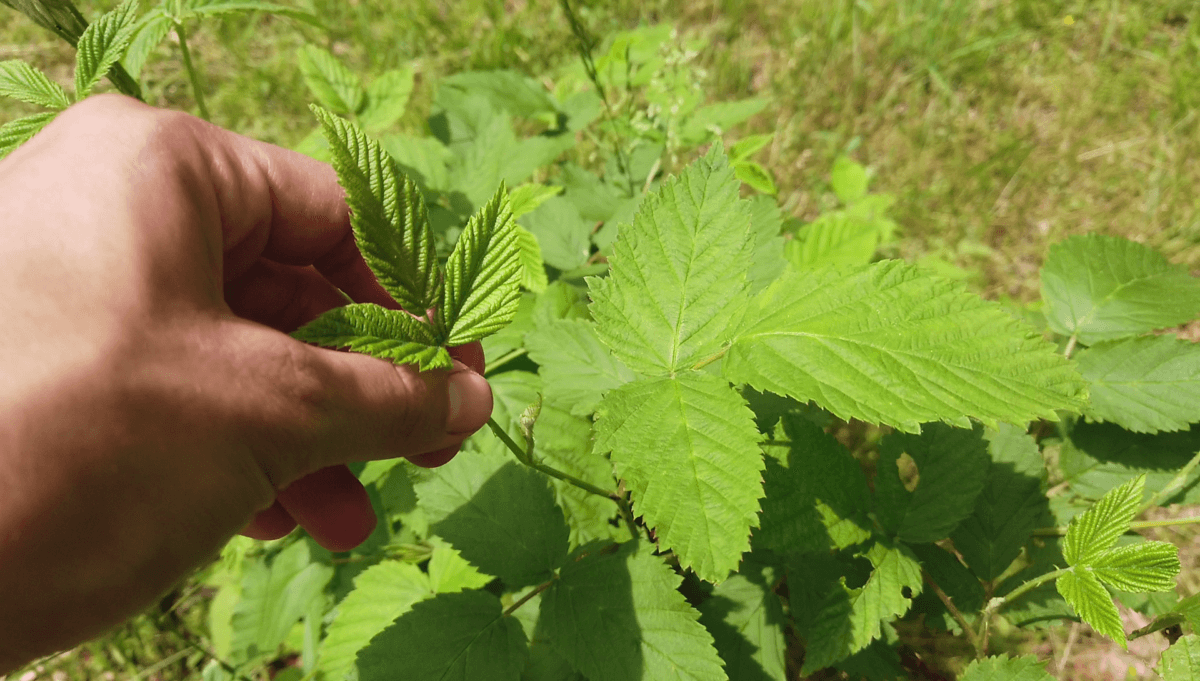

Blackberry Leaf (Rubus spp.)

In the late spring, blackberries and their cousin, brambleberries, put out a special treat of not-so-prickly leaves. When the deeply fluted, new leaves of the various members of the Rubus genus first emerge, they are downy soft and can be harvested with a bare hand. These fresh leaves make a wonderful tea, and can be harvested with abandon — whatever you pluck will be regrown quickly.

Through the rest of the year, leaves are good for picking as long as they are green. Bear in mind, however, that fully developed leaves aren’t as tender as they were in the spring, and are instead, equipped with those distinctive thorns and prickles of their own. The prickles don’t matter once they’re in the kettle, of course, but getting them to the kettle in the first place will be a bit of a stabby undertaking.

Blackberry leaf tea is bracing, pleasantly bitter, and has a faint overtone of berry. I enjoy this tea blended with red clover in the dead of winter. It makes the cold seem a bit further away.

New Jersey Tea Leaf (Ceanothus americanus)

With “tea” in the name, it’s easy to guess that this perennial shrub is no stranger to the teapot. These drought tolerant plants played an important role in the Revolutionary War when they were discovered to be similar in taste and character to imported, over-taxed teas.

True to its name, the leaves of this shrub make a truly excellent tea. Picked fresh and brewed, I find them similar in character to a grassy green tea. Dried and cured, they yield a black tea flavor.

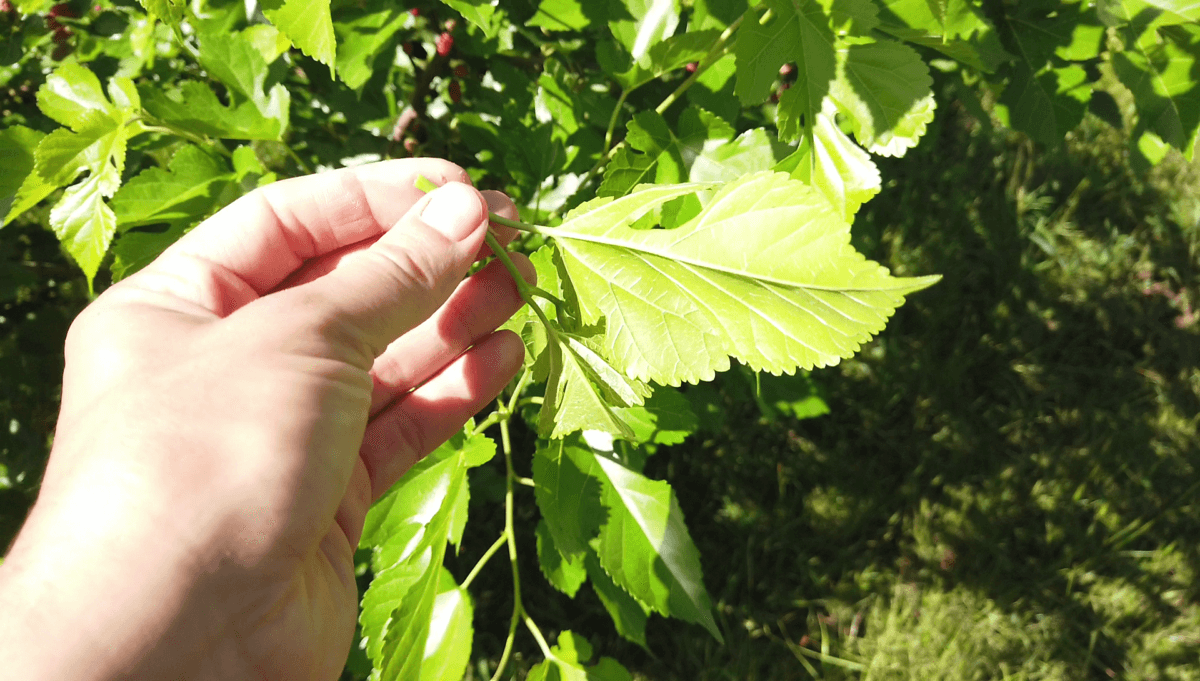

Mulberry Leaf (Morus spp.)

Mulberries of both the native and Asian variety grow pretty much across the United States from coast-to-coast, offering free berries, and for those who know their secret, ample leaves to collect. You can use them either fresh, dried, or powdered, and their taste is pleasantly vegetal with a hint of berry-like sweetness. This tea is so well liked that it’s sold commercially.

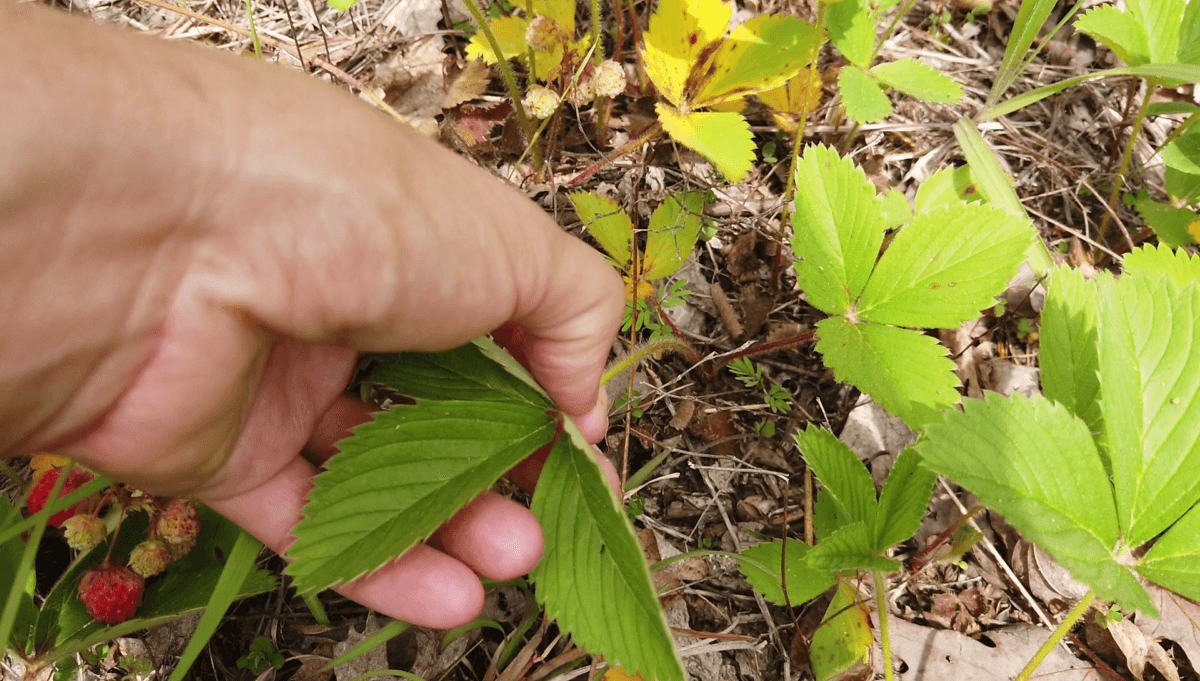

Strawberry Leaf (Fragaria vesca)

Strawberries are a short-lived spring treasure, appearing like edible rubies, and then disappearing. But the leaves of these spreading plants are evergreen, offering you the chance to harvest tea nearly year-round. Strawberry leaves dry nicely, taking on a silvery hue due to the downy hairs on their undersides. When brewed, they produce a pleasant flavor that is reminiscent of their juicy fruit, yet undeniably green and leafy. It’s good enough to brew as-is, but also blends nicely with other plants in this list.

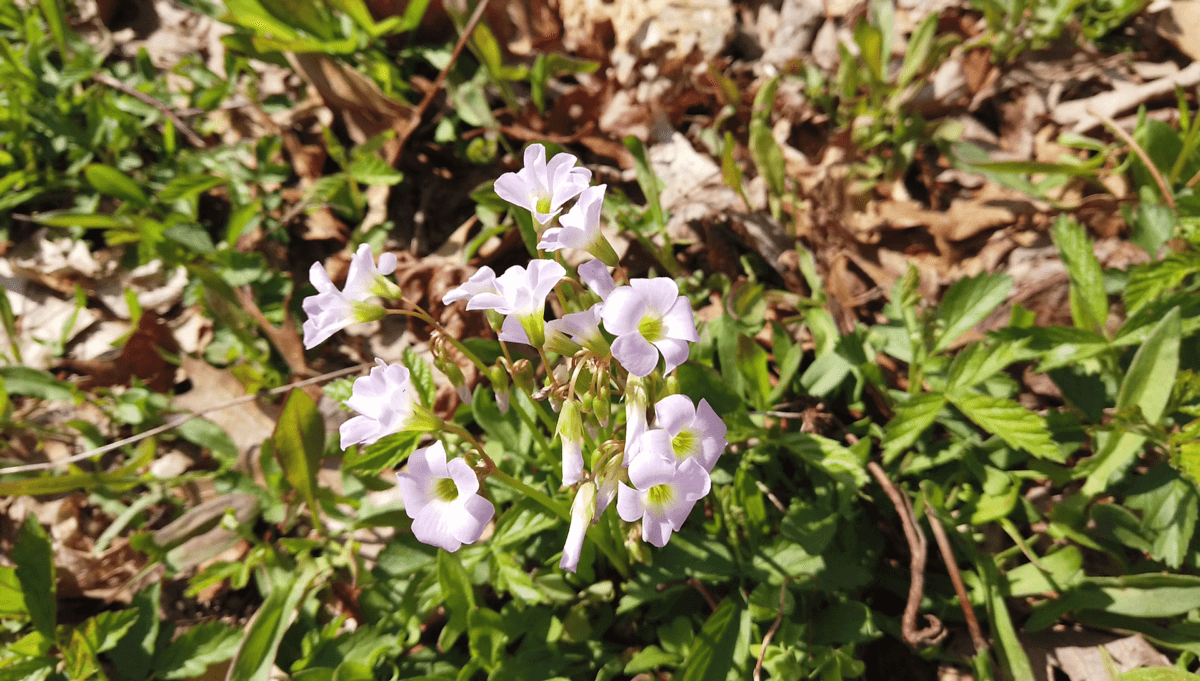

Wood Sorrel Leaf and Flower (Oxalis spp.)

If you’re a fan of lemon in your tea, try throwing in a few leaves and flowers of wood sorrel. These common yard weeds have a delightfully bright, sour flavor that fills that citrusy role with a locally-foraged twist. I must confess that I always use these leaves fresh, so I can’t confirm their viability as a dried tea. Even so, I imagine they’re best as an addition, not a base.

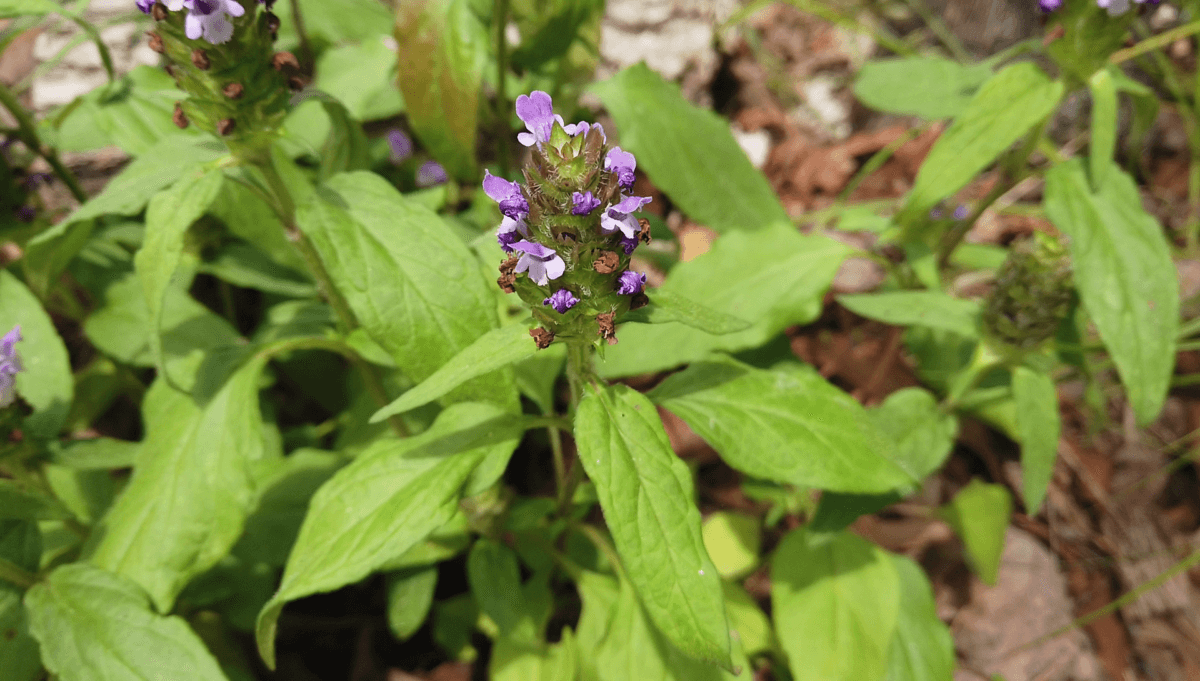

Self-Heal Leaf and Flower (Prunella vulgaris)

We’ve mentioned self-heal a while back in an earlier article on making your own healing salve. This generous healing plant is entirely edible, making it a surprising member of your tea shelf. Self-heal flowers and leaves don’t have much aroma when fresh, but when dried and brewed into a tea, they lend a special maltiness that can make a flat tea taste more “round.”

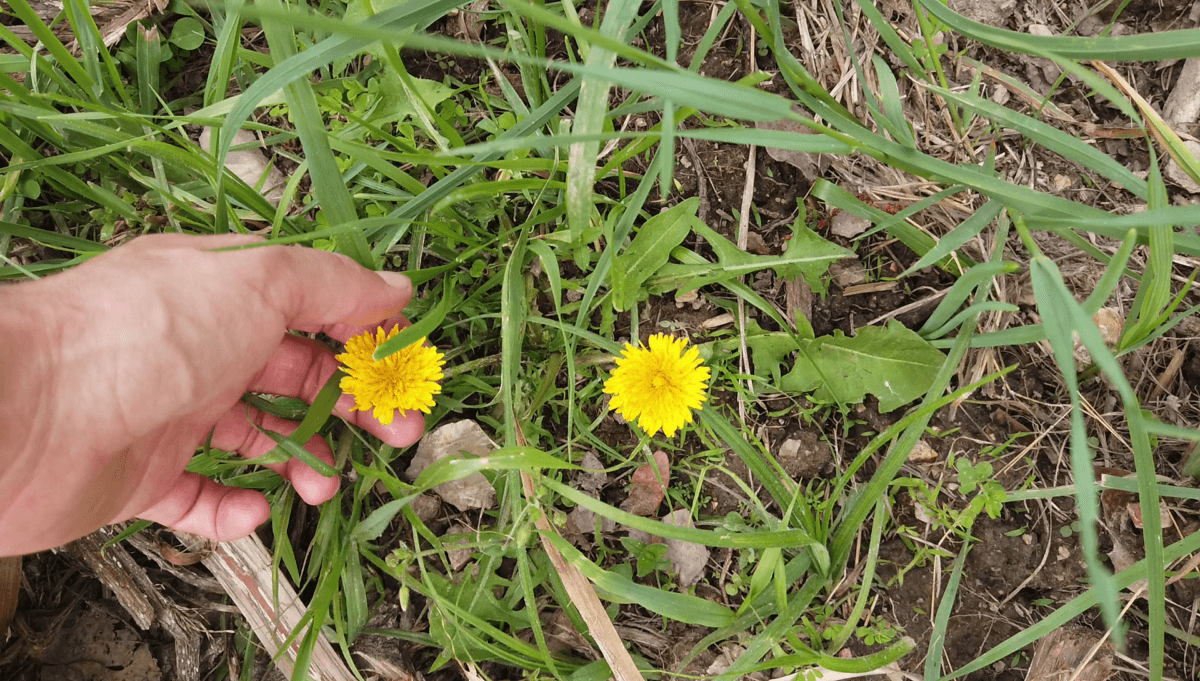

Dandelion Flower (Taraxacum officinale)

We have an entire earlier article on the various ways you can brew dandelions in a delightfully sunny tea, so I’ll direct you there. But I would be remiss if I neglect to throw their bright, easy-to-find flowers into our good-for-tea lineup.

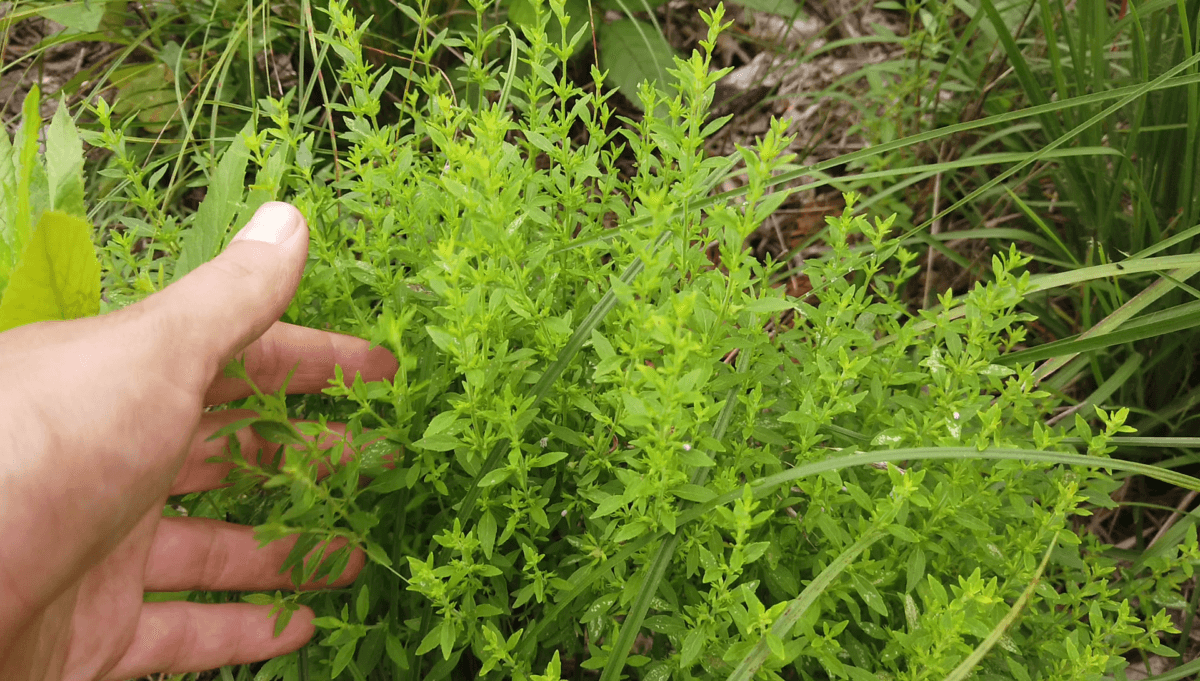

American Pennyroyal Leaf (Hedeoma pulegioides)

If you’re in the region where American pennyroyal flourishes, you’ve likely found it with your nose before your hands. This low-growing member of the mint family is small, but mighty. We go into greater detail about foraging for and drying the pungent and petite plant in our earlier article on Foraging for Wild Mints.

My favorite combination featuring pennyroyal isn’t completely wild, but worth sharing. Combine 3 parts dried pennyroyal with 1 part fenugreek seed and 1 part fennel seed. When brewed, gently sweeten with honey, and blend with milk. It may look a bit like dishwater, but the flavor more than compensates. It is my favorite goodnight drink.

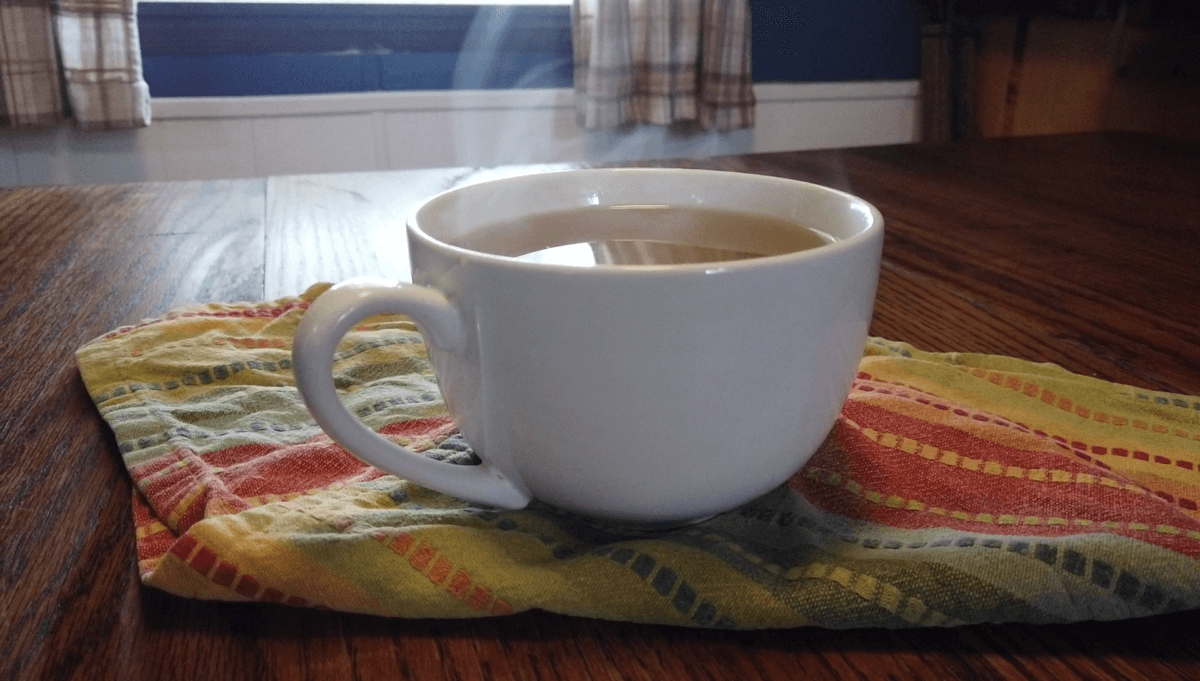

Brewing Wild Tea

If you’ve only ever made tea with a teabag, a handful of fresh or dried plant material may seem a bit awkward. Thankfully, it’s easy to translate that bouquet of foraged findings into a warm, sippable cup.

First, gently rise your plants — especially the flowers — in a quick spritz of water. You’ll often find a stowaway spider or ant, and that’s not something anyone wants in their mug.

Second, place the plants in a large pot. Cover with water and bring to a gentle simmer (except in the case of sassafras root, for which you want a rolling boil). Turn off the heat, cover, let sit for four minutes, and you’re ready to go.

Pour the resulting tea through a tea strainer or sieve into your favorite mug, sweeten with honey if desired, sip, and relax.

So that’s my favorite assortment of wild tea plants, but there are hundreds more to explore, combine, and preserve. Share your favorite findings and fixings in the comments below.

Leave a Reply