If you are a homesteader or looking at becoming one, permaculture is a topic you should do your best to understand. And even if you aren’t a full-time back-to-the-lander, the concepts and ideas espoused by Bill Mollison (creator of the term “permaculture”) will be useful to any caretaker of any amount of land. If you haven’t already done so, I recommend checking out my article on the basics of permaculture to familiarize yourself with those introductory ideas. In this article, we are going to go a deeper and look at one permaculture topic in greater depth. That topic is polyculture.

Definition and Basic Idea

Polyculture is permaculture’s answer to a more widespread agricultural planting method: monoculture planting. In a monoculture, only a single type of plant is sown. This is seen on pretty much every single large farm that you ever come across. On a tomato farm, they plant tomatoes. Apple orchards grow apples, and pumpkin patches only produce pumpkins. This method facilitates the planting and harvesting processes (which are often done using mechanical means).

Polyculture farming, on the other hand, is when several different plant species are planted in close proximity. Ideally, these different crops will benefit each other and grow better than they would if planted separately.

A Guild – The Basic Polyculture Unit

As you will soon see, you can have a polyculture that covers many acres of land, or you can have just a few different plant types in a small field. The smallest real functional polyculture unit is known as a guild. Here is Bill Mollison’s definition of a guild:

“A guild is an harmonious assembly of species clustered around a central element (plant or animal). This assembly acts in relation to the element to assist its health, aid our work in management, or buffer adverse environmental effects” (Permaculture, p. 60).

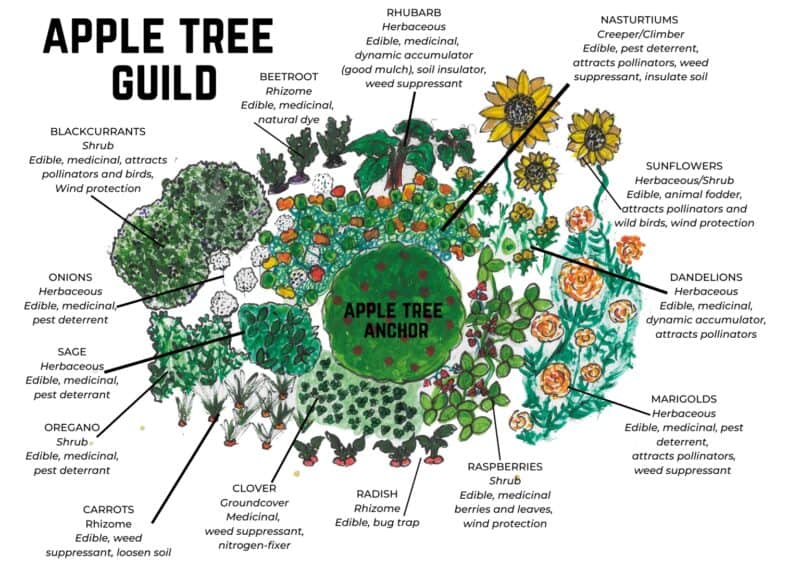

An apple tree is often used as the center element of an example guild as it is a tree that produces copious amounts of fruit for its caretaker. In monoculture systems, grass is often what grows around the apple tree. However, grass is a plant that has a negative impact on apples. In a polyculture guild, grass is replaced with plants that do not compete with the apple tree (or optimally, benefit the tree in some way). For example, comfrey is often grown around fruit trees as it does not compete with the tree for surface water (comfrey grows deep roots), and grows large leaves that shade out grass. This method of planting is known as companion planting, where companion plants are beneficial since there is no competition between them and the main crop.

Different varieties of alliums are also planted with apples as these plants grow in the spring and then go dormant during the summer when apple tree water needs are highest. Dill, in addition to other plants that host beneficial insects, is planted under the cover of the tree to assist in pest management, specifically invertebrate pests. Finally, a nitrogen-fixing ground cover like clover is often used to help add nitrogen to the soil and aid in the tree’s growth. One big happy family – that is the goal of a guild.

Levels in Polyculture

A polyculture planting not only tries to use 2D space effectively, it puts great emphasis on 3D space. Normal monoculture planting mainly considers how far apart to place individual plants of whatever type is being planted (e.g., plant your cabbages X feet apart in rows Y feet apart). In between these plants is usually bare ground, mulch, or plastic. A polyculture planting, however, considers spacing and more. It looks at the fact that different plants grow at different heights, and use it to and advantage.

Consider the apple tree example from the discussion on guilds. The tallest member of the guild is obviously the apple tree, and there is a whole lot of space between its bottom limbs and the surface of the ground. A guild seeks to fill this space with beneficial plants. The dill will actually grow quite tall and almost reach the lower limbs. The comfrey will grow a bit shorter than the dill but is still off the ground. Then, directly on the surface, you will have ground cover plants like clover and nasturtium.

Polyculture Benefits

As you should be able to gather from the above sample guild, a polyculture has many beneficial aspects.

The most significant benefit is probably the crop yields that can be produced within a given area. Utilizing the entire volume of a 3D space greatly increases the possible yield of a given acreage. Instead of just growing apples, you will harvest fragrant herbs (like dill), pungent vegetables (like onions or their relatives), medicinal herbs (like comfrey), and low-growing berries (like strawberries). And that’s an example of a single guild. The possible combinations are near endless.

Another great benefit is ecosystem health. You must remember that ecosystems are naturally diverse. Another great benefit is ecosystem health. You must remember that ecosystems are naturally a diverse place. Having a single crop species anywhere is a very artificial scenario. Visit any monoculture farm as soon as the harvest happens, and you will see an area that looks much like a moonscape – devoid of almost all life. This never happens in a polyculture system. You will never have a time where living plants are not occupying an area. This is good for the soil and for all the little creatures that rely on both plants and soil for food and shelter.

Finally, plant health is improved. In a guild, specific plants are grown together precisely to benefit one another. For example, dill and other plants that produce abundant flowers attract all sorts of pollinators to the apple tree; also, parasitic wasps and other insects that are good at targeting plant pests. Less pests means better health. In the same sample guild, the comfrey grows large leaves that shade out grasses and other competitive plants that would rob the apple tree of precious water in the summer and nutrients at times of growth.

Challenges With Polyculture

There are a couple challenges that one will face when utilizing polyculture planting.

The first is planning. With a monoculture, planning is straightforward. If you want to grow tomato plants, you need to pick a type that will grow in your area (generally based on USDA hardiness zones), and produce the type of tomato you want (e.g., paste tomatoes or slicing tomatoes). After the type is chosen, you need to figure out how many plants you need for your space. This usually involves looking on the package (of seeds or seedlings) and seeing how far apart the plants and rows need to be.

For a polyculture, you need to start the above process with the largest members of your polyculture (usually a tree of some sort). Then you need to do the same thing with every other member of the guild. In addition, you need to make sure that the individual species of plants don’t have any adverse influence on other member of the guild: If your main tree is a black walnut, you have to find plants that can cope with the black walnut’s juglone – a toxin produced by the tree that can kill other plants around it. Juglone is potent enough to harm sensitive plants within 50 or 60 feet of a large tree.

Another challenge with polyculture is having to wait for a harvest. Almost all guilds utilize trees as their main member. After planting a tree, it could take years, or up to a decade, before any sort of abundant harvest is to be expected. This can be a difficult wait. Of course, the other members of the guild will start producing far before then, but even the shrubs (like hazelnuts and berry bushes) can take a few years to produce.

The only things you can expect the first year are the herbaceous plants like dill and ground cover berries. All of this is to say that you will need to be patient, and that can be difficult when other people’s annual gardens are producing abundantly.

Conclusion

That, dear readers, is a quick rundown on polyculture – an integral part of permaculture. Indeed, you can’t really say you practice permaculture unless you incorporate polycultures on your land. I would argue that monocultures have no place on the land of any homesteader who has a long-term view in mind. They might do for the short-term, but if you’re interested in the health and well-being of your land and everything on it, you should do your utmost to bring as many guilds to it as possible. I encourage you to stick with it. It’s not something that most of your neighbors and friends will be doing, so it can be tough going, but it’s worth it in the end. Keep at it!

Featured image courtesy of Manfred Werner – Tsui on Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply