“Latin’s a dead language, as dead as dead can be. It killed off all the Romans, and now it’s killing me!”

While paging through a dusty Latin textbook from the 1930s, I couldn’t help but smile at a handwritten poem scrawled between the title page and the contents. The begrudging sentiments were well known — I’m sure the antique book was among thousands of Latin textbooks to bear the same couplet. I understand the feeling. Unless you’re a linguist, doctor, or lawyer, the practicalities of learning Latin seem pretty scant in the modern age.

I once thought that the realm of Latin was merely reserved for archaeologists, stuffy old professors, and overeducated snobs, but now, in a funny turn of events, I rely on Latin almost every day as a forager and gardener on an off-grid homestead. The reason being, there’s a realm where messing around with Latin makes sense — and that’s the world of binomial nomenclature or Latin names.

You may only know scientific names as those goofy multisyllabic streams of near gibberish that accompany descriptions of plants and animals, but by the end of this article, I hope I can convince you to take a second (or third) look at those italicized syllables, and value them in a whole new light.

What Is a Scientific Name?

At its simplest, a scientific name is a formal system for naming species of living things by giving them a name composed of two parts. Both use Latin grammatical forms although they can be based on words from other languages. Latin’s dead nature (that is, the fact no one speaks it anymore) has made it perfect to become a universal language of utility. Kind of like Esperanto.

The first part of the name (with the first letter capitalized) indicates the genus of the species in question.

The second name (lowercase) indicates the species within the genus.

This provides a succinct, verifiable, and relatively stable way to talk about specific species, no matter where you are historically, culturally, or geographically.

Scientific names allow everyone to be on the same page. A Mexican birder might say “guajolote,” and a Spanish scientist might say “pavo,” a Brazilian researcher may say “peru,” and a Canadian environmental educator might say “turkey,” but if we all point at Meleagris gallopavo, we understand each other.

And take note: You don’t need to understand or translate Latin to use a scientific name.

Carolus Linnaeus

You probably already learned all this stuff back in middle school … you know, right when the teacher was showing pictures of this guy and you were trying not to fall asleep.

If you never grew up to be a biologist, however, you probably dismissed Carolus Linnaeus and all his multisyllabic seeming gibberish. I mean, just call a butterfly a butterfly, for goodness’ sake, right?

The truth is, Linnaeus’ naming system, tongue-twistery as it may be at times, is a rather brilliant way to clarify the sometimes murky waters of biological descriptions, and it can be a literal lifesaver when it comes to pinpoint accurate identification. Which brings me to our next point …

Where Latin Is Useful on the Homestead Compared to Common Names

On a homestead, Latin matters most when it comes to plant identification. And I don’t mean pointing to a plant in front of friends and loftily declaring with snootily hooded eyes, “Oh, how lovely the Rudbeckia hirta is today, don’t you agree? And how nicely the Helenium autumnale is coming in!”

Plants exist all around the world, and like dialects and languages, they pick up different names based on local flavors, history, and uses. These are called their common name. Problem is, common names are an anarchistic, chaotically wild bunch.

What one area calls a “black nightshade,” another area calls “American nightshade.”

And what one area calls “American nightshade,” another area calls “pokeweed.”

And what one area calls “pokeweed,” another area calls “pigeonberry weed” or “dragonberries.”

And if you google “dragonberries,” you might end up looking at “dragon fruit” because the search algorithms don’t care about botanical accuracy.

By this point, even if you don’t know it, we’ve mentioned three entirely different species of plant, and it feels like we’re at the end of a SAT question from hell. It’s (hopefully) obvious that merely using common plant names can lead to confusion, and when it comes to both seed saving and foraging, that’s a big problem.

Latin exists as an absolute identifier for a plant species. No matter what dazzling array of common names a plant happens to pick up during the course of human history, the binomial gives it a specific identity that anyone anywhere can use as a reference point. To illustrate, let’s go back to our horrific black nightshade/dragonberry/dragon fruit example.

Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana)

This is Phytolacca americana, often called pokeweed but also called a host of other historical and regional names. When properly prepared, its spring shoots are a prime wild edible to forage and enjoy. You can check out our video and article on how to do that here.

Black Nightshade (Solanum nigrum)

This is Solanum nigrum, most often called black nightshade. Some resources call it toxic, other resources call it delicious (Spoiler alert: It’s delicious). It may have the same color berries as pokeweed, but it’s a different plant in every other way.

Dragon Fruit (Selenicereus undatus)

And finally, here’s Selenicereus undatus, one of the species of the bizzarre-looking dragon fruit.

With scientific names, even without photos, it’s abundantly obvious that those are three different plants from three different species. Common names are often misleading. Scientific names are (relatively) absolute.

Now that I’ve hopefully made the case for why specific and accurate plant identification is so important, here’s the two areas where I use it on a near daily basis.

Seed Saving

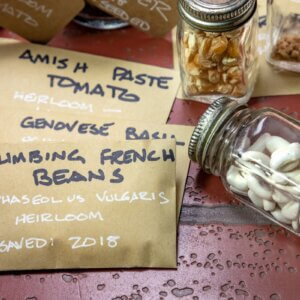

I’m passionate about saving my own open-pollinated seeds, as I hope my many previous articles on the subject illustrate.

Saving seeds requires the seed-saver to have some basic botanical knowledge so they can protect their food plants from cross-pollinating with wild plants of the same species or from different domestic cultivars of the same species.

Cross-Pollination

Say, for example, that you want to save seeds from your zucchini and spaghetti squash plants. Visually, these two garden greats couldn’t look, feel, or taste more different, right? But botanically speaking, they’re both Cucurbita pepo, and they will cross-pollinate if planted too close, resulting in some sorta spaghecchini squash in the next generation.

The same goes for plants in the Brassica oleracea species. That one, single species of plant has been bred into a dazzling array of varied forms, including:

- Cabbage

- Kale

- Collards

- Broccoli

- Cauliflower

- Kohlrabi

They’ll all cross if given the opportunity.

What You Can Grow Together

So are you limited to growing one type of squash and one type of leafy greens every year? Not remotely. Once you know, for example, that butternut squash types are a totally different species (C. moschata), you can plant them right next to your zucchini patch with nary a care.

The same goes for greens — if you’re aiming to save kale seeds, for example, you can still plant mustard greens (Brassica juncea), Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris), or turnip greens (Brassica rapa var. rapa) and have pure seeds all around.

I could give more examples, but I think you get the point. Knowing the scientific name of your garden plants is one of THE most important skills you can have if you decide to become a seed-saver.

Foraging

Free food from the fields and forests that you neither had to plant or tend? Foraging sounds like a dream come true for some of us.

Proper identification of plants is the most important step between finding a leaf on a plant and putting it in your mouth. That crucial bit of information can be dangerously difficult if you’re using common names.

Consider our earlier example with Phytolacca americana. It’s been called

- Pokeweed

- Pokeroot

- Scoke

- Cancer jalap

- Coakum

- Garget

- Pinkberry

- American nightshade

- Pigeon berry

- Pocan bush

- Poke

- Red ink plant

- Puccoon

- Redweed

- Poke sallet

- Poke salad

- Polk sallet

… to name a few. The problem is, of course, that there are other plants that share those terms — as we earlier discussed.

Puccoon, for example, is a word derived from the Algonquin word for “dye.” It applies to several plants, including goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) and several plants in the Lithospermum genus.

Inkberry is also a common name for Ilex glabra, sometimes called Appalachian tea.

American nightshade is also a common name for Solanum americanum.

I hope you see my point.

Most of us don’t have ancestral knowledge to teach us which plants are food. And most of us don’t have knowledgeable grandparents or elders to give us that knowledge. So most of us have to turn to books. Since 100% absolute positive identification is key for knowing what you should put in your mouth, knowing a plant’s scientific names is the best way to “actually really” use the field guides that will help you learn the plants in your area, and the only way you can truly cross-reference between guides.

Final Thoughts

I hope this brief article has given some worth to the scientific names you might have previously glossed over when reading about plants. Whether you’re a botanist or biologist, or someone looking to save seeds and forage great food, scientific names are there to help you along the way. It just takes a little bit of time to truly appreciate them.

Leave a Reply