Rhubarb pie does eternal battle with apple in my heart — each of them vying to reign as favorite. But I have to admit, there’s something about the tart-sweet of rhubarb that demands attention, and piques longing when it’s not there. I can’t be alone in this appreciation for rhubarb dessert. It wasn’t called “pie plant” for nothing, after all.

Maybe rhubarb will win the pie war because of the nostalgia it stirs in me. I grew up spending Sunday evenings listening to the News from Lake Wobegon and powder milk biscuit commercials of “A Prairie Home Companion.” As a child, I preferred the show’s country and folk music to the boy bands I was supposed to like as a child of the 90s.

This, of course, resulted in me being the weird girl who could be found shrieking “Beebopareebop Rhubarb Pie” while on the swings at school. I suppose it’s no wonder I eventually ended up becoming a millennial homesteader that enjoys growing rhubarb.

Related Post: Homestead Stories: Great Grandpa’s Rhubarb

So now that you’ve got that song stuck in your head, let me tell you — if you haven’t had much experience with growing rhubarb, you have got to try this delicious perennial. Both easy to grow and willing to stick around for decades, rhubarb certainly deserves being lauded in song!

Rhubarb Rhizomes Or Seeds?

Rhubarb is often sold as a big, fleshy rhizome with a growing bud, but you can also grow it from seeds if you prefer. Keep in mind that growing rhubarb from seed is and adventure of not knowing what you’ll end up with in the end (which may or may not be a deal-breaker for you). If it’s a specific cultivar or color you seek, the rhizome may be the best route.

Planting Rhubarb

Rhubarb can tolerate lots of soil types but does best in fertile, well-draining soils. If it’s put in an area with unamended clay soil, it runs the risk of rotting, so if you have a clay pit of a backyard, raised beds may be the best solution for your rhubarb location. And if you’re limited on space, you can try growing rhubarb in a pot — a really, really deep pot.

Rhubarb’s extensive underground portions require a pot that is as deep as you can afford — at least 24 inches deep and just as wide. Fill it with richly amended soil, feed with compost tea, and enjoy the company of its beautiful foliage. Also, it is essential to make sure good drainage holes are in place.

Conditions Needed For Growing Rhubarb

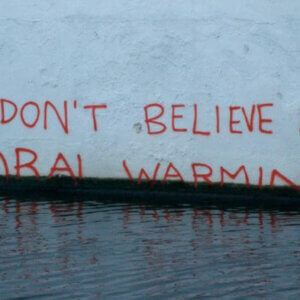

Ideally, rhubarb likes winters where the temperatures fall below 40 degrees Fahrenheit and the summers average 75 degrees. In the United States, rhubarb is grown commercially in Washington state, Oregon, and Michigan which gives you an idea of where it does best.

South of Illinois, you may have trouble getting rhubarb to thrive as it should. On my homestead in the Ozarks, for example, the often triple-digits of summer are too much for a truly healthy crop of rhubarb though I do try (somewhat futilely).

Related Post: 10 Perennial Vegetables For Years Of Garden Freshness

Some southern growers experiment with growing rhubarb as a winter annual, getting seeds in the ground in the late summer and harvesting what they can in the spring before the climate takes its toll. Whatever you decide to do, the hope of rhubarb is worth the effort!

Rhubarb does best and produces the sturdiest stems in full sun. However, if you’re a southern grower who’s pushing the limits, locate your rhubarb somewhere it will have shade during the worst of the summer’s noonday heat. Though rhubarb will probably go dormant after the thermometer hits 80 degrees, it will give you a chance to get some tastiness in the spring.

Healthy, well-managed rhubarb plants can last longer than 20 years, so when you do find the perfect site, make sure you’re okay with a giant, beautiful plant moving-in long-term. And they do grow large. Make sure that every plant is at least 4 feet away from its neighbor to avoid crowding.

Once you have the location set and the rhubarb in the ground, the next thing you’ll need to practice is patience. The first year your fledgling rhubarb pushes its attractive, tropical-looking leaves out of the ground, leave it alone. Just weed, water, and mulch it to control weeds and keep the soil evenly moist. Don’t worry — your pies are coming, just not yet. More on that soon.

As your rhubarb grows through the years, you’ll start to notice growth cycles: sturdy stalks in the cool spring, thinner stalks as the weather heats up, and a return to lush, thick growth in the fall. If you notice the stalks of your rhubarb getting skinny early in the year, it is your cue the plant is getting crowded and it’s time to divide the underground bulb.

Harvesting Rhubarb

The desired part of the rhubarb is its celery-like stalks called petioles (if you want to know the technical term). The large leaves they loft high are mildly toxic with high amounts of oxalic acid, so as tempting as they may seem, don’t eat rhubarb greens!

Once your rhubarb has reached its third year of letting it get established, you can finally harvest with abandon. The ideal time to cut or pull stalks is when they have reached the width of a finger. You can either choose to harvest it stalk-by-stalk as they reach a good size, or remove the entire clump for a huge harvest.

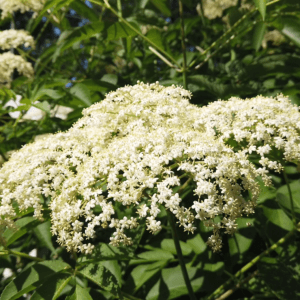

The first flush of edible goodness will emerge in the spring, giving you zesty, fruity flavors well before most other fruit has ripened. Then, once the temperatures cool for the fall, you may be able to harvest a second flush of rhubarb before winter shuts everything down. Seed stalks, however attractive their flowers are, will slow down petiole production, so remove those as they emerge to extend the growing season.

What’s The Deal With Forcing?

If waiting for rhubarb to emerge in the spring is making you impatient, it is possible to get an earlier crop. “Forcing” is the term used to describe the act of making plants grow out of their seasonal rhythms.

There are detailed directions on how to wrench an early harvest of rhubarb here, but the short version is as follows. After allowing a mature crown to go through a bit of winter freezing, dig it up, replant it in a container that can be moved indoors to a slightly warmer location (like a garage), and cover it completely.

If you keep it moist, the plant will come out of dormancy and produce a small crop of rhubarb well before the garden-bound plants reach out for the first taste of spring. Since they haven’t been exposed to the sun, bear in mind that forced rhubarb will take on entirely different colors. In some cases, this will make for more visually attractive stalks. Varieties like Victoria for example, are a muddled brown when grown outdoors but a jewel-like red when forced.

Related Post: Homestead Stories: Forcing Indoor Flowering Bulbs

Bear in mind that this practice really puts a strain on the plant itself. If you force growth out of a single plant two years in a row, you may kill it. Some people simply discard the forced rhizomes, but if you give them a year or two to recover, they’ll thank you for your kindness and produce normally again.

Rhubarb Pests And Problems

One of the sources of rhubarb’s popularity is how easy it is to raise. You really shouldn’t have many pest problems — if any — with your rhubarb plants.

Rhubarb’s biggest threats are environmental. As I mentioned earlier, the first is high temperatures. The second and probably most widespread threat while growing rhubarb is Phytophthora crown rot. This problem is incurable and emerges in plants growing in poorly drained soils.

You’ll know you made a growing location error if your rhubarb stalks are rotting at their base. Remove the plants, compost them, and start over in a better spot.

The third environmental trouble that could bother your rhubarb is drought. If you let your plants get too dry, it may trigger them into dormancy until conditions are favorable for them to grow again.

Rhubarb Background

Rhubarb has been around for a while. Chinese writings about rhubarb root use as a medicine extend all the way back to 2700 B.C. The current varieties of Rheum rhabarbarum are the result of much interbreeding between wild and domesticated strains, making its genetic history a little murky.

But what we do know is that the modern, culinary rhubarb that we now grow and enjoy was derived from plants originally domesticated in both Siberia and the Gansu province of northern China. Glance at that geographic birthplace, and you’ll quickly figure out that rhubarb is a plant that thrives best when it gets exposure to cold.

The merits of its weather hardy nature and easy care became truly valued in America around the end of the Civil War as a mainstay of homestead gardens and favorite desserts. It is even said that if you stumble across an abandoned old homestead, you’ll undoubtedly discover a gnarled lilac, an overgrown apple tree, and a healthy clump of rhubarb.

Today, there are nearly 100 cultivars of this tart-sweet vegetable-used-as-fruit, ranging in colors from green to brilliant, bright red.

Do you have experience with growing rhubarb? For all you cold-weather growers in the northern U.S. and Canada: What are your best tips for plentiful petioles? And for you daring southern growers: Have you made growing rhubarb work despite the summer’s heat? Let me know in the comments below!

Leave a Reply