Potatoes have a place in our kitchen and our culture that is unlike any other crop. They are cheap to buy and easy to grow. They are filling and delicious. From the Irish potato famine to the American potato chip, no other vegetable carries a legacy of such mythic proportions. And can you really call them a vegetable at all?

Technically a starchy tuber rather than a vegetable, potatoes fill the same carbohydrate part of the food pyramid as bread, rice, and pasta—moderately simple sugars. Potatoes stand out from this crowd because they grow well in many different climates and soils, and are very productive in small areas—much more so than wheat or other grains.

That means you can grow a lot of calories in not much ground, which has made potatoes a beloved crop around the world—and given rise to a million different inventive ways to cook them. Let’s take a look at some of the approaches to growing potatoes.

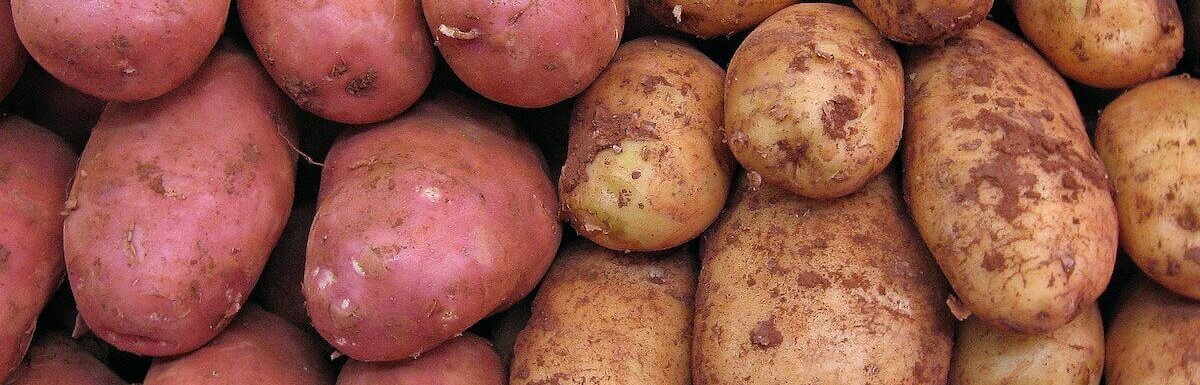

Varieties Of Potato

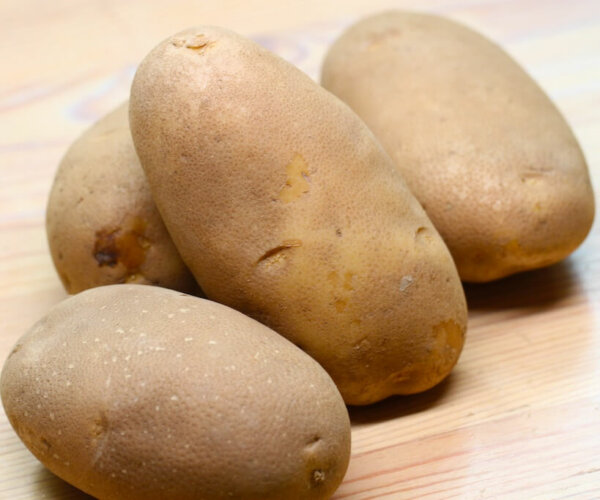

Most people are familiar with the russet potato—it’s large, brown-skinned, with a soft starchy interior. The russet is the potato of the French fry and the baked potato—when the russet potato is cooked it has a fluffy interior texture that is unmistakable. It also has a relatively low nutritional value, as far as potatoes go.

The nutritional value of potatoes varies widely between varieties. Hard, waxy potatoes like Yukon Golds have a lower starch content than russets. Red and purple potatoes have antioxidants in the pigments. As a rule of thumb, the more colorful something is the more nutritional compounds it contains. Heirloom potatoes, like the purple Peruvian potato, are less highly bred and contain a much higher nutritional value.

Potatoes grow best between 55-80 degrees Fahrenheit, although they will continue to grow in temperatures as hot as 95 Fahrenheit. They thrive in temperate climates, although many potato diseases also thrive in moderately warm, damp climates. Some types of potato have been bred to be resistant to certain kinds of disease, including the infamous potato blight.

Try growing several varieties to see what does best in your climate and ask for tips from your local garden store, agricultural extension office, or farmers growing potatoes at the farmer’s market.

Planting And Growing Potatoes

As always, prepare your beds by testing and amending the soil. Potatoes like soil with acidity between 5 and 7 on the pH scale. Like all root crops, potatoes need soil that is light and fluffy in texture and well-drained, containing lots of sand and organic material. If you have acidic soils, adding lime will help both your pH and your calcium levels, giving you a more successful crop.

Potato seeds are … potatoes! If you’ve ever seen potatoes sprouting in your cabinet … yup, that’s how potatoes grow. Each growing nub is called an eye. When you buy seed potatoes, find the eyes and cut the potato in half or thirds, as long as you have two to three sturdy-looking eyes on each chunk. That way, you get more plants per pound of potatoes.

Once cut, planting potatoes is easy. Dig a trench and bury the potatoes about 4-6 inches deep and 8-12 inches apart. Mound soil over them and water them in. Keep them weeded and watered, especially in the early part of the growing season. Once the plants have established themselves, they provide good soil coverage with their leaves to out-compete weeds.

There are lots of different ways to grow potatoes in small gardens or even on balconies. One estimate is that you can grow up to 100 pounds of potatoes in 4 square feet of ground. That’s probably all the potatoes one person could eat in a year —2 pounds a week—without getting really sick of potatoes. If you’re planting in a container or a limited space, you can keep adding soil at the base of the plant as it develops to encourage the potato to set more tubers along its root system.

Potatoes will be harvested all at once and then stored, so you don’t have to plant successions.

Growing Potatoes In Containers

There are lots of different ways to grow potatoes in small gardens, or even on balconies. One estimate is that you can grow up to 100 pounds of potatoes in four square feet of ground. That’s probably all the potatoes one person could eat in a year – two pounds a week – without getting really sick of potatoes.

Potatoes can be grown in any large container, from a raised bed, to a plastic bin. If you are repurposing a container like a plastic bin, poke holes in the bottom for good drainage. Be sure to put something under it to catch the excess water.

If you’re planting in a container or a limited space you can keep adding soil at the base of the plant as it develops, to encourage the potato to set more tubers along its root system. This “vertical planting” allows you to grow significantly more potatoes per square foot of soil.

Troubleshooting Diseases

Potatoes are very susceptible to disease. Potato diseases can be bacterial, fungal or viral.

Bacterial diseases include various kinds of rot, which can attack the stem, leaves, roots, or tubers. Rot turns various parts of the plant gray or black and slimy. Planting clean seed is important in preventing transmission of bacterial disease. We never save our potatoes for seed—each year we buy new potato seeds from a reliable seed distributor. This is the primary preventative measure for some diseases and important to combine with other preventative tactics for others.

The famous potato blights are fungal infections—there are two varieties, early and late blight. Symptoms are black or brown spots, leaf-yellowing and withering. As their names suggest, early blight can come on at any time and is not usually as serious as late blight, which is triggered by wet weather and will kill potato plants and ruin crops.

Potatoes are also susceptible to powdery mildew, a fungus that infects many crops, including cucumbers and squash. Try not to over-water as bacteria and funguses both thrive in wet, warm conditions. Well-drained soil and a wide planting space helps prevent trapped moisture encouraging fungus. Some potato varieties are more resistant to blight than others.

Good biosecurity means not transferring diseases from one site to another or harboring them on your property year to year. If you visit another agricultural operation, always wash and bleach your boots before and after, or wear a different pair to prevent transferring soil diseases. Although potatoes are tempting to save for seed, it is more important to plant clean seed. Wash and disinfect all your equipment at the end of the season, including shovels, boots, and tractor tires.

Dead potato plants for compost and cull potatoes should not be included in your regular compost facility unless you use a hot-compost method. Instead, burn or bury your potato waste 3 feet deep. Likewise, your kitchen compost should not be included in the compost you spread on your fields since it contains not only potato peels but any pathogens remaining on the food you bought from a grocery store or farm.

If you begin to have pests or if you notice a plant showing signs of disease, always catch the problem early. When potatoes start to show signs of late blight, the easiest course of action is often to just harvest quickly, before the blight infects the tubers. Best practices in biosecurity, crop rotation and early action can save you big headaches in potato diseases.

Harvesting Potatoes

Potatoes have a relatively long window of harvest. You can start digging the smallest potatoes after the plants start flowering—just about 5 weeks from planting with some varieties. However, the plant won’t have produced its maximum potential crop by then. The ideal time to harvest potatoes is when the top of the plant has begun to die back.

Potatoes need to be dug out of the ground before the first hard frost or before wet weather arrives, whichever comes first in your climate. Freezing will damage the starch texture and storage potential, and prolonged damp soil will speed the rotting process and encourage blight. It is okay to harvest and eat potatoes from a blighted plant as long as the potatoes themselves aren’t shriveled or moldy looking.

Harvesting potatoes is simple but laborious. The soil has to be turned over and loosened, the potatoes picked out by hand or with a machine. You can buy walk-behind potato harvesters that do both these steps for you, but the classic method is with a shovel and a little help. Start digging at the outside edge around the plant, not at the base of the stem so that you get as many potatoes as possible without damaging them with the edge of the shovel.

Damaged or bruised potatoes will begin to spoil faster, so dig gently and don’t throw potatoes around. They look sturdy, but they can still get damaged. Freshly harvested potatoes usually have thinner, flakier skin, which doesn’t protect the potato as well as a hardened skin. They are good for eating but less than ideal for storing.

Potatoes harvested for storage should not be washed—the drier the potatoes, the longer they will last. To help the skins harden, after harvest, leave them out to cure in moderate temperatures between 45-60 degrees Fahrenheit. During curing, the potatoes shouldn’t be stacked or piled, and they should be in a dark, dry area where they can completely dry.

After being cured, potatoes keep for three to six months in a cool, dark place. Like all storage crops, one bad potato will begin to spoil all the others, so check your stores regularly for any rotting, molding, or slime. Remove any potatoes beginning to go soft or mushy, usually early signs of spoilage. It’s okay if potatoes begin to wither, sprout, or turn green. Just cut off the green bits and the sprouting eyes.

Shepherd’s Pie Recipe

There is perhaps no more diverse vegetable than potatoes—since the introduction of potatoes to Europe and the globalization of food, most cultures around the world include recipes with potatoes.

Baked potatoes, mashed potatoes, potato salad, potatoes au gratin, hash browns, latkes, boiled, roasted, fried. It’s so hard to choose just one, but one of my favorite childhood dishes was shepherd’s pie.

Ingredients

- ½ pound cubed or ground meat of your choice—substitute mushrooms for vegan option

- 2 cups of broth (meat or vegetable)

- 1 ½ pounds potatoes, cubed

- 2 tablespoons butter (or olive oil)

- 1 cups milk (or substitute)

- Diced vegetables—onions, carrots, peas, celery, mushrooms

- Flour or cornstarch for thickening

- Salt to taste

- Season to taste: thyme, oregano, basil, marjoram, rosemary, black pepper, bay, Worcester sauce

Directions

- Preheat the oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Saute onions and meat on the stovetop until cooked and brown.

- Add additional vegetables and pour in the broth.

- Turn down the heat to a low simmer and add the thickener, stirring steadily until broth thickens.

- In a separate pot, boil the potatoes until tender. Drain the water and put them in a bowl with melted butter and mash until smooth, adding milk gradually until it achieves the desired texture.

- In a cast iron, casserole dish, or ramekin, fill the dish with pie filling and use a spoon or pastry bag to top the pie filling with mashed potatoes. Place the dish in the oven, cooking until the potatoes on top begin to brown. Serve hot.

Whether you are just starting out or if you are an experienced potato grower who is looking for new tips, always remember to ask other gardeners, local experts, farmers at the market, specialists at your county extension or members of your local master gardener program. As always, when we are farming or gardening, the most important thing we are cultivating is community.

Leave a Reply