The rhyme says that April showers bring May flowers, but the experienced forager knows that March rains bring violets.

The revision doesn’t have the same lyrical flow (or cheesy, following historical joke), but for those hankering for fresh greens after a long, cold, winter, poetry is found in leaves, not words. Furthermore, violets aren’t only a spring treat. Once the summer has run its blistering course and acorns start dropping from the oaks, these generous perennials make an encore appearance and give the forager one last harvest of deliciously edible greenery.

You may have seen violets as a weed in an unsprayed lawn or as a pleasant sign of spring, but I hope to introduce you to this widespread plant as a valuable source of food as well.

Watch The Video

Finding and Identifying Violets

No matter where you live, there’s a local species of violet to be found. They grow coast-to-coast, north-to-south, and in a huge variety of environments from marshy forests to dry pine glades. Every species of violet is edible, though some are certainly more desirable than others. You’ll have to taste and see for yourself.

Violet leaves are so varied — even within species — that botanists are sometimes at odds with each other over which species is which, or if one species actually counts as two separate species, or whether two or more different species should really be counted as one. The best identification feature is the blossom which, thankfully, is similar across all species. They are five-petaled, but the petals are irregular with two distinctly paired on the top, two to each side, outstretched, and one at the bottom that often has purple streaks. If you squint at it upside-down, you can almost see a little person, with a big, stripey, yellow-spotted head, two arms (often complete with hairy armpits) and two legs.

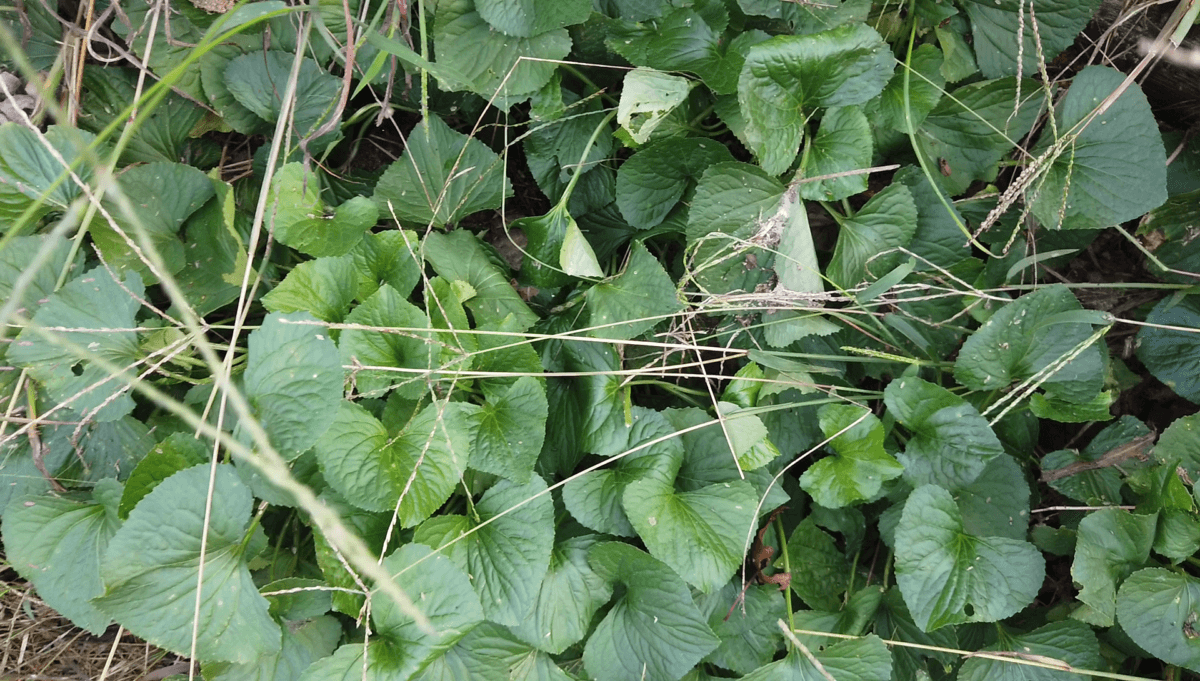

For the purposes of this article, I’ll be focusing on the common blue violet (Viola sororia). It’s the easiest to identify, and it very well may be the most widespread. Common blue violet grows heart-shaped, scalloped leaves that extend up from a center root mass and form a dense layer beneath their purple flowers.

You’ll also see, however, some images of birdfoot violet (Viola pedata). This violet species is abundantly common on my Ozark hill in the spring as it’s a fan of growing in dry soil near pine trees. The leaves of this species are palmate and so deeply cut that they are nearly fernlike in character. I honestly don’t bother with collecting these leaves, because the abundant profusion of blossoms above them is far more worth my time. Probably no other violet offers so many blooms at once, sometimes carpeting the ground in an unbroken blanket of lavender, white, and purple. They are easy to gather by the handful if you’re on the hunt for blossoms but I admit some springs, I can’t bear to ruin their showy display. I guess I’m a sucker for butterflies and honeybees.

Violet Look-Alikes

Since there are more than 70 species of violet found in the United States alone, all of them with incredibly variegated forms within species, this is a strange section to try to clarify. Thankfully, violets are friendly to the forager. As I said earlier, every species is edible, and their flowers are consistently shaped from species to species. The only problem you may run into is when you’re harvesting from unflowering plants.

Samuel Thayer points out that there are some species of violet with palmate leaves which may be confused with the early leaves of larkspur or pre-flowering buttercup species, both of which are toxic. If you find that palmate-leaved species of violet are common in your area, the best safeguard I can recommend is waiting until they flower to harvest their leaves.

Harvesting Violets

Violet leaves are a spring delight, offering up some needed greens after a winter of root vegetables and starchy staples. Picking leaves in quantity is surprisingly easy, and as you may find, almost a cut-and-come-again wild vegetable. As soon as you get all the tasty greens from one stand, you’ll find the one that you harvested last week is lush and ready to pick again.

I commonly use my hands like a violet-leaf-harvesting comb, working my fingers beneath the leaves, clenching them together, and twisting to wrest the lovely leaves from the stems. In the height of spring, and again as the fall rains return, you can easily collect leaves by the basketful.

There’s no worry if you do get some stems, by the way — all the aerial parts are edible even though I find the stems a bit tough later in the season. The root mass underground is suspected to be toxic, but it would be foolish to pick it anyway. You’d be killing off future harvests.

Violet leaves are usually pretty clean pickings though they have a tendency to collect bits of dirt on their undersides after a spring rain. I usually wash mine in several changes of water to ensure the grit is kept to a minimum.

A second product violets offer is their flowers. Despite a lovely appearance, they taste much the same as the leaves (at least, as far as common blue violet is concerned. Some species have a wintergreen flavor). That said, they’re a fun nibble in the field, especially for children, who can never seem to get enough of the bright blossoms. They’re so plentiful, there’s no harm in letting the little ones graze like sheep.

You can collect blossoms for use in tea and medicine, but they require some careful drying. One spring, I painstakingly collected enough flowers to fill a mason jar; no small undertaking, considering they shrivel up to a fraction of their original size. I was fairly confident that I had thoroughly dried them before putting them in storage. But when winter came and I wanted to brew some purple tea to remind me of spring, they had transformed into a furry lump of gray mold. To say I was disappointed is an understatement. I now store my dried blossoms in the freezer where they’re just as easy to access, but there’s no chance of my efforts turning to dust.

Cooking Violets

Violet leaves are edible raw, and since they sprout at the same time as chickweed, can be easily gathered for a fresh, green spring salad. For raw eating, the slightly unfurled leaves that are a lighter green are the best pickings. Violet leaves are also a good addition to any of your green smoothie recipes. They are sweet and mild, imparting a vegetal flavor without a trace of bitterness.

When cooked, violet leaves have a mucilaginous quality, and so much so, they’re sometimes referred to as “wild okra” when put in soups. I find that they absolutely shine when blended into a green paste and used for a wild version of saag paneer. They retain a brilliant green color, which makes for an eye-catching and delectable presentation. You can find our recipe for wild green saag paneer (and more) here.

You’ll often find recipes for violet flowers online: violet jelly, violet salads, candied violets, and violet blossom smoothies. The lovely, purple-y pigment of violets is water-soluble, so inventive cooks have taken advantage of that feature for eye-dazzling culinary effects. Despite the lovely appearance, you’ll need to prepare yourself for the fact that violet blossoms don’t add much flavor.

But they do have one fun feature. When brewed into a purple infusion, they change to a bright pink blush if an acid is added. This means, you can make a sweet, violet-blossom tea, then add a dash of lemon for color-changing pink lemonade. Kids (and adults) will likely be thrilled, and what a way to celebrate spring.

As a final note, violet leaves and blossoms brewed into a tea, are a traditional throat soothing remedy for those colds that seem to emerge alongside spring flowers.

I hope this article reaches you before the fall violets have faded away for the second time this year, and you’re able to gather one last harvest before the leaves cover the ground. If (for whatever reason), you’re unable to make it this fall, rest assured that the violets will be back in the spring, ever lush, ever available, and a rich reward for those who see them as food, not weeds.

Leave a Reply