Winter is long. Even if you have a well-stocked root cellar brimming with canned goods and root vegetables, by the time January and February roll around, most anything that was green is long, long gone. And if you’re like me, your eyes and palate might start yearning for that verdant, lively color to return.

Watch the Video:

The first plants to start growing at the end of winter, then, are of special significance to any forager. They tell us that our seasons of gathering and savoring have returned, that the bleak, gray landscape isn’t dead — just waiting (and soon) to wake again.

For me, field garlic is that hope-filled plant. Its long, grassy leaves emerge well before the grass begins to regrow, and its bright, spicy flavor is a welcome, fresh taste for the seasonal eater.

Finding and Identifying Field Garlic

Allium vineale, sometimes called field garlic (or confusingly called wild onion, onion grass, crow garlic, or wild garlic) is a common plant found in much of the eastern United States and along the western coast. Since it easily hitches a ride in fill dirt, however, it can also be found in many places outside its normal range. It thrives in sunny areas and can be found in lawns, pastures, vacant plots, and parks. You’ll likely never find it in the forest or in really old fields succumbing to forest succession.

Of all the wild alliums — onion family plants — field garlic is certainly the most successful. It’s everywhere! Though it’s called “field” garlic and sure enough, is found in fields, it could easily be named “next to the path” garlic, or “I just weeded that lettuce, how is it there???” garlic. That tenacious growing tendency is a tip-off that this plant is a non-native invasive. We have several native alliums such as ramps (Allium tricoccum) and similarly-named wild garlic (Allium canadense), and while they do sometimes make large colonies in their own right, they typically will not be found in a lawn or pasture.

In the early spring, garlic is often the first plant to appear green in what is likely an area of dried brown grasses. It may look like grass at first, but the earliest growth often has wonderland-like curlicues. And if you inspect a clump of it more closely, you’ll soon see that each leaf is a distinctive round, straw-like tube — not a flat blade-like grass. As with every member of the onion family, these leaves have a strong, distinctive oniony smell when broken.

The first spring leaves are the most tender. As the spring turns to summer, the plants will grow taller and straighter, usually reaching past your knees. By this point, they will be much tougher in texture. They produce an edible, pinkish flower that becomes a bizarre cluster of bulblets (complete with bitty leaves) once fertilized. It becomes so heavy that it drops back down to the ground and ends up planting a whole clump for next year — a key to field garlic’s wide-spreading success.

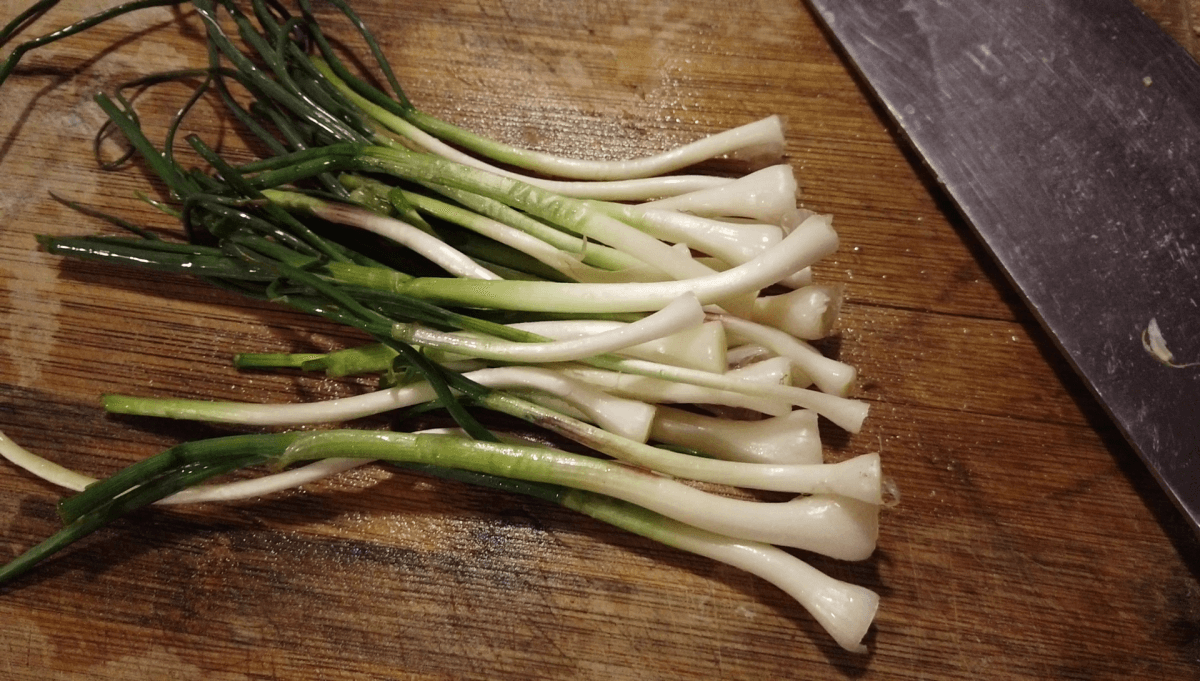

Beneath all that upper growth, there is a white bulb, usually firmly rooted, growing a few inches under the soil. It’s much, much smaller than any garlic bulb, and has a great flavor. Usually, when talking about wild bulbs, this is the part where I should caution you about overharvesting, and advocate for not removing bulbs. But since field garlic is invasive, and since harvesting the bulb often loosens tiny side-grown bulblets and leaves them behind to grow next year, there’s little chance you’ll eradicate field garlic when harvesting … even if you tried.

All the same, the leaves and roots pretty much have the same great, garlicky flavor. If you want to harvest sustainably — or if you are on someone else’s land and they don’t want you to dig — the leaves easily tear away from the deep-rooted bulbs without disturbing the roots.

Related Post: Foraging for Pokeweed

Lookalikes: Watch out for Star-of-Bethlehem!

Be aware of one significant lookalike. Star-of-Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum) is a similar-looking spring flower that you need to know (as well as you know field garlic) before you begin your spring harvest. Every part of Ornithogalum is toxic, and so it obviously shouldn’t make its way to your dinner table.

The glossy, green clumps of leaves emerge well before the attractive flowers that lend their name. It is also a rather invasive, early-emerging plant that likes the same sort of environment that field garlic enjoys. The problem is, it often grows side-by-side with field garlic, and without its distinctive white, starry blooms, it may be easy to overlook while gathering your early spring greens.

Here are three ways to distinguish Star-of-Bethlehem from field garlic. Be sure to use all three in tandem to harvest safely and confidently.

Smell: Star-of-Bethlehem notably lacks the onion smell of the allium family, which is one easy way to distinguish individual plants from each other. This, however, makes a strong case for not gathering indiscriminate handfuls when you are out in the field. It would be very easy for a few Ornithogalum leaves to secret themselves between onion-smelling, field garlic leaves.

Sight: The leaves of Ornithogalum are solid blades with a u-shaped cross-section, and they’re full of a gooey sap — not hollow (like straws) as with field garlic.

Bulb: Field garlic leaves start out as dark green, then gradually fade to white as they join up with the bulb. Additionally, field garlic leaves are sheathed over each other. Ornithogalum leaves are the same bright green all the way down to the root, where they abruptly join with a white bulb. Additionally, the leaves do not sheathe one inside the other.

Harvesting Process and Tips

The entire field garlic plant, from stem tip to bulb-y root, is edible. If you want a simple harvesting endeavor, however, just grab the leaves. The green tops readily break from their bases and have the same spicy flavor the whole plant shares. The best time to harvest leaves is early in the spring when they’re still tender.

If you’re looking for a more substantial amount of food and don’t mind digging, you can, of course, dig up the whole plant. It usually does require digging — at least in my area, the bulbs tenaciously stick in the ground and only can be pulled up once the soil has been loosened. I usually employ a hori-hori knife around the whole clump and spend some time wiggling it around before I try to pull. If you pull too soon, the leaves will break off, and then you’ll have to try to get the bulbs out without a helpful handle. Bulbs can be dug at any point of the year, but they’ll be biggest in summer after the field garlic leaves have browned. Whenever you dig your field garlic, be sure to fill the hole back in when you’re done.

Bulbs will usually be caked with mud, so give them a rinse in a bucket before you bring them inside the kitchen. I usually douse my haul in a bucket and give it a few good shakes in the water to loosen up any grit and rocks. Wash them again once you bring them inside, of course, but doing a field rinse like this is an easy way to keep the mud from dirtying your kitchen.

Related Post: How to Store Garlic

Field Garlic in the Kitchen

True to its name, field garlic tastes quite garlicky! The flavor is a bit more grassy and buttery, and sharper by my perception. In the early spring, it’s a wonderful change from the mellow roots and bread we’ve been eating. Field garlic would be overwhelming in its own right, though — think of it more in seasoning terms. You can use the young plants much as you would chives. They add the same bright green pizazz and sassy onion flavor. Field garlic shines in soups, stews, omelets, pasta dishes, and pretty much anywhere you want a fresh onion-garlic flavor. My favorite way to enjoy it is to finely dice the whole plant, sauté it in a tablespoon of butter, and use the flavorful, green-flecked pan for omelets. If you find that the leaves have become too tough to cut or chew easily, they still make an excellent flavoring for a soup. Bundle them bouquet garni style and simmer away in your next broth.

You can eat the whole thing raw as well, and my favorite way to use it raw is to finely chop the tender spring plants and mix them with salt, pepper, and hot pepper flakes. Douse it in olive oil, and use it as a dip for fresh-baked bread.

Field garlic is a gift, the first entry in a yearlong, multicourse meal that is freely served up in the fields, forests, and abandoned lots all around us. I hope that you can join me this spring and summer, and enjoy this persistent and pervasive little plant, adding another delicious flavor to your foraging know-how.

Related Post: 8 Winter Vegetables You Should Plant In Your Garden

Leave a Reply