Before I moved to my homestead, I was gifted a huge jar of heirloom seeds by a friend who understood what we were trying to do and had experience in seed saving.

I remember dreamily sorting through the tiny baggies of beans, kale, and beets; my inexperience and ignorance of gardening temporarily gilded with happy visions of bountiful future harvests.

At the bottom of the box, there was a set of instructions on seed saving that came with a strange ending exhortation: “If you save seeds from your harvest, you’ll never need to buy from us again. We wish you well!” They must have been homesteaders, too.

Years later, with many miles and gardening seasons between me and that first moment, I can confirm the promise of those farsighted seed sellers. With a few additions, that box has been my garden ever since. Some of the seeds I planted the first year were allowed to mature and produce seed, giving me seeds not just for the consecutive planting seasons, but for as long as they were continuously planted either by me, the people I’ve shared my surplus with, or the generations who followed.

The heirloom seeds I’ve carried on aren’t my own creation. They are a continuation of a heritage of seed saving that has kept and improved those old varieties for hundreds, or in some cases, thousands of years. It’s a tradition that anyone who plants a garden can take part in, if they so choose.

Now, the practice of seed saving for the next planting season may seem like a relatively simple endeavor, but it actually has a learning curve that I hadn’t anticipated back when I was sorting through that box, so many years ago. I should mention before we get much further, that if you’re unfamiliar with seed saving, you should check out our earlier article on the basics.

I now have a few gardening seasons under my belt and a few lessons learned that books never taught me. With the hope you too can start your home’s own seed vault, I offer here my tips and tricks from our organic, heirloom-seed-run homestead that may help you along the way to seed self-sufficiency.

Seed Saving Terms You Should Know

Heirloom Seeds

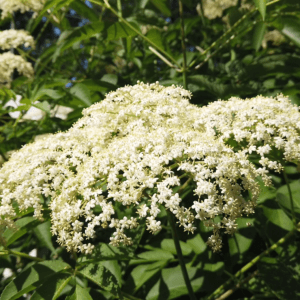

Most of us know about the wonderful colors and shapes of heirloom tomatoes at the local farmers market, but a surprising amount of people don’t realize that term extends far beyond tomatoes. Heirloom vegetables, fruits, flowers, and herbs are seeds that are open-pollinated, can breed true, aren’t genetically modified, and (in some cases), have been around for thousands of years.

Hybrid Seeds

At their simplest, hybrid plants have been created by cross-pollinating two different varieties of the same species, but in the modern day, this can also mean plants that may have been crossed with different species, genetically modified, or otherwise altered in ways beyond their natural, normal scope. Hybrids do not typically breed true, and may even produce sterile seed.

Pure Seed

Heirloom seeds that reproduce true to type aka just like their parent plants.

Breed True

The ability of heirloom plants that have been fertilized by the same variety to result in bearing pure seed.

Open-Pollinated

A plant that can be pollinated through natural processes including self-pollination, wind pollination, and insect pollination.

Self-Pollinating

Plants that are able to fertilize themselves and therefore produce pure seeds automatically.

Insect Pollinated, Wind Pollinated

These are plants that require wind or insects for fertilization, and require isolation from other varieties to bear pure seed.

5 Things I Never Knew About Seed Saving

Now that we’ve covered the basic jargon to know about seed saving, here are five things I didn’t know about saving seeds that I learned after my first few seasons.

1. Saving True Seed Requires Knowledge and Planning

If you have an heirloom plant, you have a treasure — a link in an unbroken chain of plants that have been grown and allowed to produce pure seed. Your garden becomes a continuation of gardening generations who selected strong, vigorous plants and passed on their offspring.

In order to keep that chain unbroken, however, you need to protect your blossoming crops from cross-pollination. You’ve probably heard of hybrid dogs and hybrid chickens, but cultivars of the same type of crop can hybridize too. Avoiding it is not just a matter of planting just one type of cabbage and one type of turnip. Plants in the same family can hybridize as well.

I learned that the hard way when I saved zucchini seeds one year without taking into account that I had also planted two other summer squash varieties in close proximity. Once you decide to become an heirloom gardener, you’ll need to become familiar with the different families of garden plants and how they are pollinated. You’ll quickly learn which plants can cross, and then you can plan accordingly.

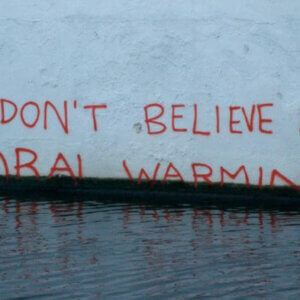

Here are some (but certainly not all!) examples. There are four distinct species of squash, and they’re all insect-pollinated and liable to cross within species. You could either choose to grow only one type of a family per year, or try your hand at hand-pollination and bagging blossoms. Corn is wind-pollinated, and even if you only plant one type of heirloom corn, your seeds may be hybridized if a close neighbor is growing a different type, or if you’re across the road from a GMO cornfield.

Related Post: Heirloom Seeds: What Are They?

Domesticated carrots are the same species as wild carrot (Queen Anne’s Lace) and will be hybridized if their wild counterparts are growing nearby. You can suspect hybridization if your saved seed from an orange type carrot starts producing white carrots. The cabbage family includes arugula, kohlrabi, kale, broccoli, and mustard, just to name a few, and they all mix freely.

Does the prospect of keeping all these botanical family lines in order make your head spin? I hope not. I prefer to see it as a jigsaw puzzle that I get to solve, close to the wood stove in the winter, as I plan out my garden every year. And the nice thing is, there are some common, self-pollinating crops that are a hassle-free way to cut your teeth on seed saving.

If you’re new to this, try your hand saving seeds from heirloom peas, tomatoes, eggplant, lettuce, cowpeas, and Chinese long beans. They’ll easily produce true seed and shouldn’t cross with anything.

If you (like me) want to raise heirloom crops for the long haul and are excited by the challenge, I’ll recommend this excellent resource on garden plant families, pollination styles, and how to keep them all straight: “Seed to Seed” by Suzanne Ashworth. It is my go-to reference for figuring out what’s getting planted in my garden every year so I can plan which plants will be allowed to go to seed, and keep my seed vault pure and strong.

2. Some Seeds Take a Very Long Time to Mature

When you get into seed saving from biennials, you are in it for the long haul. The name literally means “two years” as some plants will take a full two years to produce mature seed.

The first time I saved parsley, for example, I was shocked to find the seeds I planted in April of 2017 didn’t give me more parsley seeds until September of 2018 (it was worth the wait, as one single seed became hundreds). In the meantime, I got a minor harvest of parsley leaves for tabbouleh and pasta salads.

Related Post: How To Choose, Collect, And Save Garden Seeds

If you have limited garden space, understand that your biennials will take up residency for longer than the radishes and lettuce that happily go to seed within a season. A strategy for managing this is to plan to save one or two biennial seeds a year. You’ll wind up with hundreds of seeds from most plants which keeps you from having to overwinter each plant every year.

Plan to save from cabbage and beets one year, rutabaga and Swiss chard the next, and so on. Keeping a garden journal or logbook is an important means to keep track of your plans and make sure you have all the seeds you need for every season.

3. Seed Saving Requires a Lot of Space … in Addition to the Garden Space

On our homestead, we plant dozens of different species of garden plants nearly year-round, trying to get as much goodness from our food plots as possible. As a result, I’m nearly always in some stage of processing seeds at any given part of the year. Once I’ve harvested a mature fruit or seed stalk, there are a few places they may need to go.

Even if they’re mature, many seeds still need to finish drying completely to be stable and storable. Any moisture left behind in the seeds can spell fatal disaster in airtight and frozen storage. In the drying meantime, they also need to be protected from nibbling rodents and opportunistic birds. We solve that problem by having a dedicated seed-drying dehydrator (aka a repurposed freezer). It’s usually full to the brim most of the year.

Some seeds need to be threshed, hulled, or otherwise cleaned after drying. Other seeds — such as tomatoes and cucumbers — need to be fermented for a few days to separate the seed from the fleshy pulp surrounding them. All seeds need to be labeled while they are processed to keep the varieties from getting mixed up. Finally, your saved, dried seeds need to be carefully packaged, labeled, and stored so that all your hard work can be ready to grow in the next planting season. This all adds up to quite a production!

One of my kitchen shelves becomes “seed processing land” every year. It’s a worthy use of space, however, and I delight in packaging up all the bright, shiny, fuzzy, or pebbly bits of future gardens like the treasures they are.

4. Saving Hybrid Seeds Might Still Be Worth Your Time

With all this discussion about preserving heirloom seeds, it can be easy to think that messing around with hybrid seeds is not worth your time. I (and others!) am here to assure you that is anything but true. As long as the hybrid was still pollinated naturally and produced viable seeds, those seeds want to grow, and they don’t really care what their label was.

And while the results will be anything but predictable, it can be a worthwhile and exciting endeavor if you have the garden space for it. After all, a lot of heirlooms had their start as happy accidents or intentional crosses. Generations of selective breeding have stabilized them into true seeds.

Back when I was very new to seed saving, I saved seeds from everything even if I didn’t know the variety. Store-bought tomatoes, farmers market squash, fallen fruit in the countryside — everything was a seed to gather, dry, and try to plant. My naive enthusiasm was worthwhile, however, as it taught me about the potential in seeds and the excitement of trying to cultivate new varieties.

For example, I planted seeds from a mature mad hatter hybrid pepper given to me by my sister. From the seeds that sprouted, I got a single second-generation pepper plant that was an unexpected carbon copy of the original hybrid, and a few other plants of tiny, fiery hot, intensely fruity peppers that I couldn’t get enough of.

Seeds from both were saved and will be planted. After a few generations, maybe I’ll end up with my own, stable variant of mad hatter pepper, and a second bonus breed.

I also planted seeds from a farmers market tomato when I didn’t know the variety. It had apparently been a hybrid because the resulting plants weren’t anything like the big, juicy slicing tomato they had come from. Instead, I was rewarded with an incredibly productive plant that produced tiny, berry-like fruits that looked nearly identical to the original wild Peruvian tomato that all tomatoes descended from.

They were intensely sweet and produced well past my other tomatoes, so their seed has also been saved so we always have a “snack tomato bush” somewhere in the garden.

That all said, not every experiment has been successful, of course, but I’ve learned with every seed I’ve planted.

I tell these stories to try to fan the flame of experimentation and exploration that created the hundreds of thousands of varieties of garden plants. Every seed you plant in the garden is a result of humans selecting for traits they liked and continuing to practice seed saving from successive generations. Do you have a green thumb for adventure? Who said we ever have to stop discovering?

5. Mature Fruits Don’t Look Like Anything You’d Expect

You may not realize it if you are used to grocery store produce, but the mature forms of garden vegetables sometimes don’t look like those you’ve bought before. It isn’t really until you start the practice of seed saving that you realize that the majority of vegetables we eat are eaten before they are mature. Sweet, young zucchini, crisp green cucumbers, shiny eggplants, and delectably tender okra are all plants eaten in their infancy.

Once you start seed saving, you’ll learn that every fruit needs to reach maturity to have mature seeds within. And sometimes that maturity can be super unexpected. Mature pickling cucumbers are staggeringly huge and turn a wonderful orange or deep yellow with hard skin.

Mature eggplants have lost their luster, but the dull skin covers their brown, hard seeds. Mature okra can become unexpectedly huge too, with a tough outer shell that rattles with promise. The plant that has surprised me most is Swiss chard. A plant that was a handful of succulent, loosely-clustered leaves the year before has transformed into a huge, sprawling seed stalk covered with gangly arms and bizarre nubbins of seeds emerging from every inch.

Though these matured fruits are certainly past their prime eating-wise, it doesn’t mean that they’re all inedible. I’ve made fine salads out of ripe cucumber (it’s opaque white and a bit tough, but still tastes pretty much like cucumber when the dressing is on it) and savory soups with giant, fully ripe zucchini. If all else fails, chickens usually appreciate vegetable bits that others don’t.

My adventures and misadventures in heirloom seed saving are still progressing, but I hope this article inspires you to give it a try. Learning how to save seeds, improve varieties through careful selection, and experiment with crossing strains used to be a natural part of gardening.

Adding seed saving to your homesteading tool belt will serve to make you more self-sufficient, more knowledgeable, and more connected with your garden plot. If you have additional resources, please share them in the comments below, and I’ll leave you with some of my favorite resources for finding heirloom seeds and learning how to continue their cultivation through seed saving.

Leave a Reply