I know, I know, as you’re browsing all the excellent articles on Insteading, you see that this one is about soil pH and you probably want to just gloss on past it. When there are tomatoes to pluck, chickens to chase, and compost to turn, rehashing 9th-grade chemistry terms might seem a bit dry.

BUT WAIT. Hang with me, and I’ll try to make it worth your while. Because while those growing tomatoes may be alluring and the compost is looking ready to spread, the soil that unites the whole garden is where the action is really happening. And the pH of your soil is kind of where it all hinges, believe it or not!

So let’s talk about why soil pH is important, how to evaluate the pH of your own plot, and what to do to make this spring the best planting year yet.

A Quick pH Primer

If your understanding of pH is a bit foggy in the first place, here’s a quick recap of what it’s all about. pH is used to evaluate the acidity of a material, on a scale from 1 to 14. The lower the number, the more acidic a material is–lemon juice, for example, usually registers around a 2 or 3.

The higher the number, the more alkaline the material is — lye registers close to 14. 7 is the neutral zone, where something is neither acidic nor alkaline. You should know, by the way, that this is a logarithmic scale — that means that each increasing number represents a tenfold change. Soil that has a pH of 5, for example, is a full 100 times more acidic than neutral (7) soil. That bitty number change actually indicates a huge difference.

Why You Should Care About Soil pH

Essentially, pH is a gateway to whether or not essential plant nutrients are getting into the soil, and that’s a big deal. An ideal garden pH of slightly acidic 6.5-7 is like a babbling brook, gently releasing nutrients from the soil to plant roots at an appropriate rate.

Now, if the soil is too acidic, everything is dissolved so readily that they flood the growing vegetables with toxic levels of nutrients. In too alkaline soil, nutrients are essentially “locked up” in a scarce trickle of availability, and plants that aren’t adapted to those conditions can’t get them easily.

Related Post: Soil Testing

The pH also dictates what micro and macrofauna can happily exist in the soil itself. Beneficial earthworms, for example, don’t like highly acidic soil, but those pesky wireworms do. Some diseases like potato scab are more prevalent in alkaline soil, which is one of the many reasons why potatoes prefer slightly acidic soil.

What’s the Best pH for Soil?

This is not a straightforward question. Most soils in the world range somewhere between 4 and 8 and pretty much all of those soils have some sort of specifically-adapted plants happily growing in them. The level of calcium in the soil controls the pH. If it is often washed out, as happens in well-draining soil, the pH can tend toward the acidic side of the spectrum.

Now, the “best” soil pH really depends on what you’re wanting to grow. Ornamental plants often tolerate a huge range of conditions. Rhododendrons, heathers, blueberries, and cranberries demand acidic conditions. Fruits generally grow best in a slightly more acid soil pH of 6 or 6.5, while most vegetable plants do better in a soil that’s just barely acidic, and close to 7.

Related Post: How to Make Soil Acidic: 3 Natural Methods That Work

As far as the backyard gardener is concerned, a slightly acidic environment is what you want. A soil pH between 6 and 7 is what allows for most of the natural soil processes that plants depend on to function at their optimal rate.

Finding Your Garden’s Soil pH

Generally, gardens in the eastern United States are acidic, and gardens in the West are alkaline. But let’s skip generalities — how do you go about understanding the pH of the specific soil in your specific garden? The first approach is the simplest: plant vegetables and see what happens.

That’s what I did on our homestead the first year I gardened here, and the strengths and weaknesses of my personal plot became apparent after a growing season of working with it. As it pertains to this article, I was able to understand the soil pH of my garden through failure.

I planted both Swiss Chard and Beets, dreaming of wonderful leafy greens and purple-stained fingers. To my delight, the chard flourished and grew strong. To my dismay, the beets barely sprouted, and the sprouts that did emerge faltered and died.

I remember crouching over my sad, prostrate beet seedlings in frustration, then looking up and trying to figure it out. My gaze went past the fields behind the garden, nodding with pussytoes and sprays of wild blueberry branches the distant blue-green haze of shortleaf pine. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the answer was right in front of me–fallen evergreen needles create acidic soil, and plants like pussytoes and blueberry thrive in it.

I found later that swiss chard is far more tolerant of acidic soil than beets. Though it was a somewhat circuitous route to figure it out, I now know that my gardens tend to be a little more acidic than some vegetables like. And from there, I have learned to sprinkle wood ashes on my beet plot with success.

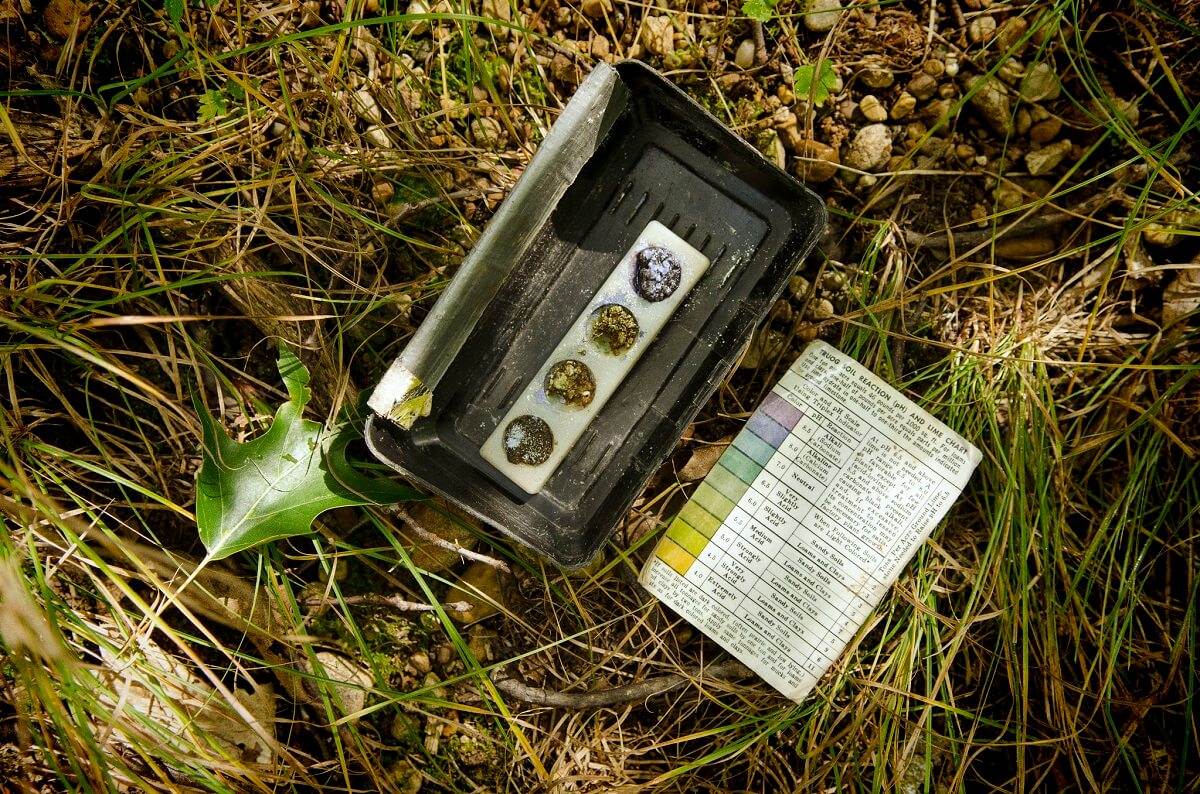

Now, if you want a number to work from, rather than just observational data and a potential lost growing season, a pH test kit is very easily available and gives you results in seconds. These kits are easily acquired from any garden store, and usually, just require a bit of soil dissolved in water to get a result.

And of course, as many middle-school science students may have learned, Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla) is a natural soil pH indicator. Many people in your neighborhood may have these big-bloomed beauties as a decorative element–if the plant in your yard and your neighbor’s yard is all pink, then the alkaline soil of your area is above 7.

If the blooms are blue, you can reliably guess that you have acidic soil that has a pH below 6.5. If there are flowers that are both pink and yellow or a weird, purple mix of the two, the soil is probably a nice, neutral 7.

Ways to Work With Your Soil pH

I like this perspective from Eliot Coleman, author of the fabulous book Four Season Harvest and hard-working soil-salvager.

“The initial test of our soil in Maine showed a pH of 4.3 (very acidic), and a note from the soil scientist warned that the ground did not seem suitable for agriculture. Well, every soil can be made suitable, and the first step was to spread limestone to make the soil less acidic…the soil was very sandy, so we added some clay…we added rotted manure…we also raked up autumn leaves and…tilled them into parts of the garden…It took a few years and some energy to convert that poor Maine soil into a bounteous vegetable garden, but success was inevitable. No matter what you start with, it is possible to build soil conditions for optimal plant growth.”

Now, wherever you’re starting soil pH-wise, the best way to start improving it for garden growth is to add compost and decomposed organic matter. These soil improvers always stabilize soil pH, whether it’s too acid or too alkaline, and will do nothing but help you in the long run.

While adding store-bought amendments can help you correct one season’s worth of growing, the long-term solution is to always have a compost pile or a leaf mold pile and do the years-long work of adding organic material to your plot every season.

That said, there are amendments that can be mixed in to improve growing conditions in the short-term as well. As I get into these mix-ins, please remember EASY DOES IT. It’s far better to add a little less than you actually need than to overdo it and cause further problems in your soil’s pH than you had when you started.

Add Limestone or Sulfur to Adjust Soil pH

General book-gardening advice says to add ground limestone to acidic soil to raise the pH and sulfur to lower the pH.

The amount of limestone that’s appropriate to add depends on your soil type. Burpee’s advice for raising pH one unit is as follows:

- Sandy soil: Add 30 lbs ground limestone per 1,000 square feet

- Loam soil: Add 70 lbs per 1,000 square feet

- Clay soil: 80 lbs per 1,000 square feet

The amount of sulfur that’s appropriate to add also depends on your soil type. Burpee’s advice for lowering pH one unit is as follows:

- Sandy soil: 10 lbs of sulfur per 1,000 square feet

- Loam soil: 13 lbs per 1,000 square feet

- Clay soil: 20 lbs per 1,000 square feet

Natural Alternatives to Adjust Soil pH

Of course, anyone who has read my articles for any length of time knows that I’m very loathed to ever recommend buying Bags o’Stuff that you can’t generate sustainably from your own land. And thankfully, you don’t have to. Wood ashes have been a traditional “soil sweetener” that can raise the soil’s pH and also add phosphate and potassium to boot.

It is more water-soluble than ground limestone and also slightly caustic, so it’s best to add wood ashes only in the spring and to use it with a light hand — no more than 2 lbs per 100 square feet every year. If you have access to it locally, natural calcium sources are also a great way to raise the pH, such as ground eggshells, ground clam shells, and ground oyster shells.

For a more sustainable way to lower the pH, make a batch of oak leaf mold, or spread pine needles, sawdust, wood chips, or fresh manure. You’ll often see sphagnum peat as a common organic recommendation for making the soil more acidic, but if you research even a little into the mining and packaging of this limited natural resource, you’ll see that it is both destructive and hardly sustainable. Better off with the free stuff that’s naturally found on your land anyway!

Finally, if, despite your best efforts, the environmental conditions of your specific garden patch just constantly tend away from that lovely, workable pH of 7, don’t fret. With a bit of research, you can figure out how to select plants that work beautifully in less-than-ideal circumstances.

Some plants that will easily grow in soil with a pH as low as 5.5 include carrots, celery, endive, garlic, radish, watermelon, rhubarb, eggplant, and sweet potato.

Plants that can work with soil with a pH over 7 include asparagus, beets, celery, cucumber, sunflowers, New Zealand spinach, onion, okra, garlic, and leeks.

I know it may seem like a sidebar to the seeds and tools and lush squash that are easy to Instagram, but the more you understand about pH, and the more you understand how to work with what you’ve got, the more important your soil pH will become!

Resources

- Grow Organic, Edited by Louise Abbot

- Four Season Harvest, Eliot Coleman

- The Complete Vegetable and Herb Gardener, Karan Davis Cutler

A refreshing publication, this reminds me of my school days in agriculture. Thanks and hopefully i could again read some more in the future especially in agriculture.

Am 60 years old and into free range chicken and gardening. Am from the Philippines.