The first zucchini I ever ate came from a dumpster—or, rather, from a cardboard box next to a dumpster, also filled with various greens, peppers, and hummus. Many of the foods in the box were foreign to me, at least from a culinary standpoint, but they were free and I had a family to feed, so I was willing to try anything that could help stretch my food budget.

Little did I know that the valuable items I found while dumpster diving behind grocery stores would make me a better, more creative cook over the long term.

The dumpster in question is behind Cid’s Food Market, the only locally owned grocery store in Taos, New Mexico. Every day, employees gathered bruised, blemished, and just-ripe fruits and veggies, along with other perishables that were past their sell-by date, and put them in a cardboard box (or boxes) next to the dumpster for the taking.

Cid’s is closed on Sundays, so Monday was the best day to check for discarded produce. Monday’s treasure trove of goodies could help supplement my family’s meals throughout the week.

Why Do People Dumpster Dive?

My dumpster diving background isn’t unique in Northern New Mexico. Homesteading is a big deal in rural Taos County, where I spent several years of my life in the mid-2000s. I lived off the grid in a sort of makeshift community known as “the Mesa,” and worked odd jobs while also raising three small children.

Poverty is also kind of a big deal in Taos. U.S. Census Bureau data from 2016 indicates that 22.4 percent of Taos County residents live below the poverty line, which is significantly higher than the national average of 12.7 percent.

Poverty is a multidimensional issue, but some of its root causes are universal. Taos County is somewhat of a hotspot where income disparity and homelessness are concerned, both in the town of Taos as well as rural areas. For example, Paseo del Pueblo, the main drag of Taos and home street of Cid’s Food Market, has seen an influx of homeless squatters in recent years.

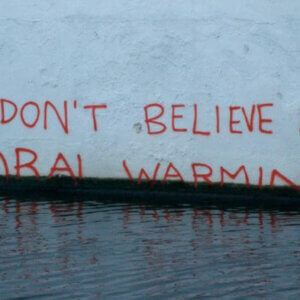

But dumpster diving isn’t reserved exclusively for homeless populations. It can be used as a form of protest against food waste or for more practical reasons. My friend Kory, who lived just outside of Taos in Arroyo Hondo, sometimes used Cid’s dumpster produce boxes to supplement the regular feed he gave his goats, Moe and Dalawn.

The Lost Art of Cooking

My cooking skills were acquired later in life, but I guess I should be grateful that I learned to cook at all, so much that it’s one of my favorite extracurricular activities.

It’s embarrassing to admit, but I couldn’t even make a grilled cheese sandwich at the age of 14. My first grilled cheese solo attempt resulted in a soggy mess with blackened edges, essentially unfit for consumption. I don’t know what I would have done with a zucchini at that time—probably put it in the trash.

As it turned out, when I found myself with several slightly blemished and discarded zucchinis years later, I had at least a modest idea of how to prepare them. I chopped the zucchinis and fried them in an oiled skillet with other fall vegetables including diced potatoes, onions, garlic, and a red pepper.

The seasoning was simple, just salt and pepper, and the result was marvelous. The dish remains one of my go-to sides, and sometimes I throw in cabbage, mushrooms, or green chiles for added pizzazz.

Today, my cooking skills stretch well beyond vegetable stir fry. I know the best spices to use on different meats, what a mango looks and feels like when it’s perfectly ripe, and how to make gravy from scratch.

Many of those skills are directly connected to random foods I came across during my homesteading days, as I struggled to feed my family using all available avenues. And my dumpster diving-based culinary knowledge is unique among my peers, as well as my fellow Americans. Indeed, cooking is essentially a lost art.

According to the Harvard Business Review, 45 percent of Americans “hate” to cook. A further 45 percent are more ambivalent but don’t claim to enjoy cooking. Those individuals view cooking as a necessity of life, and nothing more. Apparently, I am part of the 10 percent of people in America who love to cook, and that fact makes me sad.

Conclusion

I’ve been a city dweller rather than a homesteader for almost a decade now, but I haven’t lost my love for cooking, whether it’s experimental or traditional. And I’m grateful every day for the culinary lessons that dumpster diving taught me, albeit accidentally. Along with zucchini, other edible “firsts” I can attribute to Cid’s discarded produce include fresh coconut, papaya, and tabouleh.

As someone who was raised in America’s Heartland, where cherries are considered “exotic,” zucchini wasn’t the only kind of produce that was foreign to me. Fresh mangoes brought to mind sandy beaches and palm trees, and I never would have expected that the juiciest, most delicious one of my life would come from the trash.

On one particularly fruitful Cid’s dumpster dive excursion, I found a pair of mangoes so soft and ripe they felt like they might burst. My children and I shared them almost immediately, simply cutting the mangoes into wedges. Using their teeth, the kids scraped every bit of the rich orange meat from the rind and begged for more. To this day, I can’t test grocery store mangoes for ripeness without thinking of that blissful moment.

I wonder if Cid’s still puts produce outside its dumpster. If so, I wonder if the contents of its produce boxes have inspired others to become more creative in the kitchen.

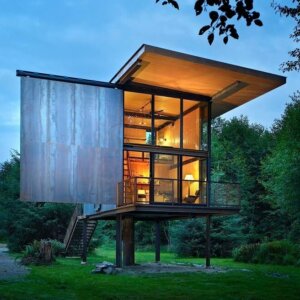

Leah D. Nelson writes about music, sustainability, and traveling, and is currently based in Boise, Idaho. She and her partner, Sandro, are in the midst of a DIY tiny house project. Where they will end up once the house is finished is anyone’s guess.

How interesting! I wasn’t sure what to expect at the start of the article- were you literally taking food from the dumpster? At least the store is putting the edible food- even its not the prettiest- in a place where someone can benefit, and not directly in the trash. There must be so much waste coming from the larger supermarket chains!