I have been waiting for this day all fall. Specifically, I’ve been counting down the days until November 1.

You see, now that the money-grabbing fall holiday has passed, the money-grabbing winter holiday is steamrolling its plastic, glittery way into place. There’s no room for the two to share. Thus, anything fall-themed absolutely needs to be ousted from the big box stores and grocery stores ASAP.

And that, dear Reader, is my time to quietly harvest something precious: food for the winter.

All those huge, “decorative” pumpkins that were selling for $8 or more are suddenly worthless!

Well, to the stores, maybe, but not to me.

You see, once upon a time, these weird, warty, heavy-skinned pumpkins were far, far more than porch eye-candy. They were nutritious heirloom varieties of squash specifically developed by patient gardeners for centuries. But rather than being valued for mere aesthetics, they were developed with outstanding flavor, giant size, and long-storing qualities. Among the hundreds of varieties of heirloom squash, you’ll find lumpy, bumpy, green Hubbards, graceful-necked Cushaws, dusky-brown Musquee de Provence, retro-blue Jarrahdale, or multicolored Turk’s Turban. All of them are full of fascinating histories and good eating. They may be labeled “clearance bulk pumpkin at $1 each.” But they are still food, just as they always have been.

For the homestead or home looking to put away food for the winter, you have a huge opportunity, right now, to rescue these useful and undervalued squashes before they end up in a dumpster. I brought home more than 150 pounds of long-storing food for $24. Where else can you find food at that price nowadays?

So, have I piqued your interest? Read on to learn how to participate in your own great pumpkin rescue!

Are Those Pumpkins Edible?

Yes. Every pumpkin or squash was bred and developed to be food. If you’re unsure about that fact, bear with me for a few botanical paragraphs so I can explain why you can trust it.

I’ll start by asking you to please use discretion when you read about “pumpkin edibility” online. Most blogger-folks are not farmers or gardeners and don’t really know what they’re talking about. My first three hits on multiple search engines for “are decorative pumpkins edible?” all turned out to be factually incorrect in some way (mostly about mixing up gourds and squash, which I’ll explain below). I’m not trying to sound like a know-it-all. After all, I’m just another of many voices online, but I hope that I can give you the knowledge to understand, and therefore, mentally turn these squashes back into food rather than holiday decor items.

Online and in stores, the terms squash, pumpkin, and gourd are used recklessly and interchangeably, leading to confusion.

Squash

Squash is a big term that covers many species in the Cucurbita genus. This includes the four main squash families that are used for food in the United States: C. angyrosperma (sometimes called C. mixta), C. pepo, C. moschata, and C. maxima. All of your summer and winter squashes are found in those families. The bulk pumpkins being sold right now are all technically winter squashes.

Pumpkins

Pumpkin is a nonspecific term that describes hundreds of varieties of squash from C. pepo, C. moschata, and C. maxima. There is no pumpkin species, so the term is used however people want to use it.

Related Post: Growing Pumpkins

Gourds

“What about gourds?”, well, they’re complicated. The baggies of tiny, decorative gourds in stores now are either tiny squash from the C. pepo species that’s potentially edible, or a true gourd (which is decidedly not). Hard-skinned gourds are a separate genus (Lagenararia specifically). Though a few varieties of true gourds are edible when young, they were traditionally developed for use as vessels, not food. Those being sold for table decorations are all mature, so any gourds in the mix are beyond edibility.

Decorative gourds from a farmers market may be larger than the ones at the big box supermarkets, so try to find out what they are before assuming they’re squash and blindly making a soup. If they are thin-fleshed and bitter, they’re gourds, and not edible.

So, I hope that explanation clears things up. In this article, I’ll use the terms squash and pumpkin interchangeably.

Storing and Using Your Rescued Pumpkins

First, it starts with finding unwanted squash at a grocery store. Usually, after October 31, they’re in a big bin near the front door or outside. If you get to harvest from a clearance bin, try to be discerning with which squash you select for storage. Any with their stems broken will deteriorate more quickly than their stem-intact counterparts. This isn’t to say they’re useless, however. Just plan on using any dented or stemless squashes first.

Now, rescuing that heaping batch of pumpkins only matters if you use them, of course. And part of that is storing them properly so they can last you the whole winter. Folks might mistakenly believe that pumpkins rot quickly — but that’s because their main experience is probably with carved pumpkins that are left on cold, wet autumn porches. There could be no worse storage situation.

Winter squash are, in truth, amazingly long keepers if given the proper environment. And thankfully, it’s easy to find. The ideal storage location for squash of any size is your kitchen (no root cellar needed). Warm, dry locations like that give squashes the best chance for long-term survival (until you eat them, that is).

I store my squash all over my kitchen and living room. They line the floor of the bookshelves, get tucked under benches and tables, and make impromptu “sculptures” around my kitchen island. It may seem like there’s less floor space, but it’s a small price to pay for having a huge supply of stable, winter food.

As you slowly eat them through the fall and winter, be sure to give your rescued pumpkins a weekly once-over. Though you may now value them as your food, they’ve been through a lot before they got to your kitchen. Earlier rough handling may have bruised them, and bruised areas start to rot if undetected. If you find any areas that look a bit darker than their surroundings, have wrinkles, squish a bit under pressure, or (worst of all) are leaking liquid, get that squash to the cutting board, pronto. Even if a bit has gone bad, you may be able to salvage the bulk of it.

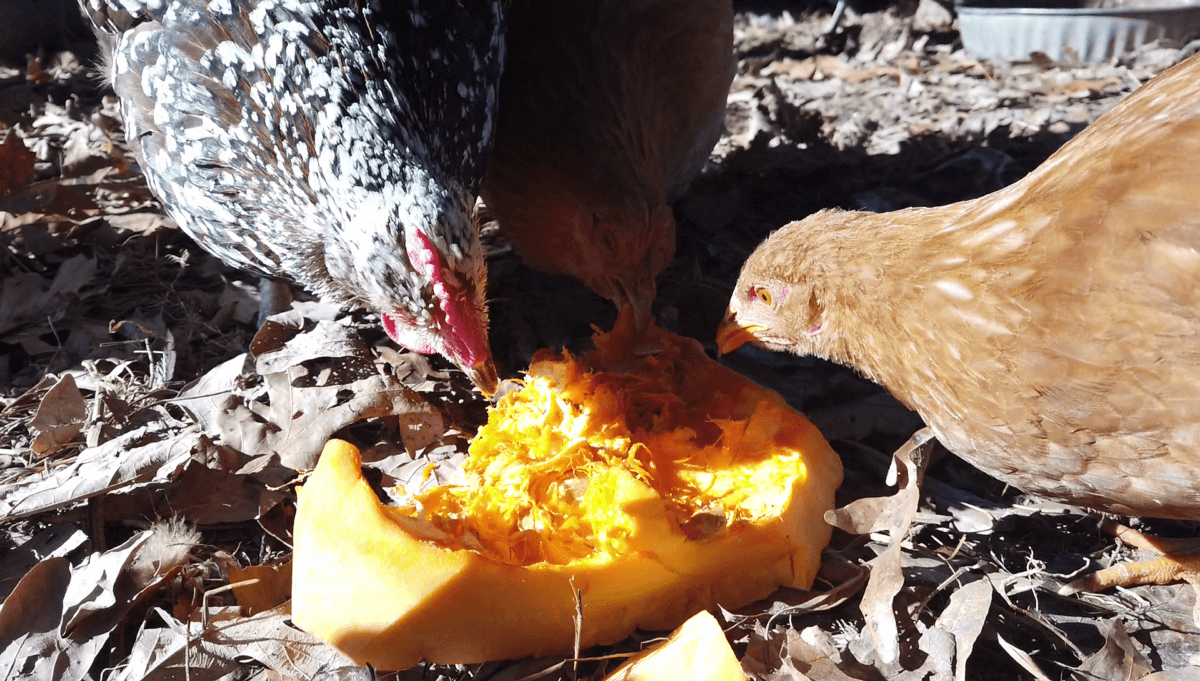

If the bruised rot is isolated to a small area and hasn’t gotten to the seed-filled core, cut it out, throw it to your chickens, and enjoy the unblemished portions. But if the bruise has rendered the greater part of the pumpkin soft, slimy, smelly, moldy, or otherwise unappetizing, it’s a goner. Just be aware that if you compost it whole, you may end up with 300 pumpkin plants in your compost pile next spring.

Now, some of these heirloom pumpkins are big. Like, 15 pounds or bigger! Those are my favorite. I understand if the thought of figuring out how to cook all 15 pounds of squash in one meal is an overwhelming prospect, and storing that big hunk-a-pumpkin in the refrigerator is an annoying space-waster. Thankfully, you don’t have to do either. Pumpkins and squashes can happily sit on a counter for a few days while you hack off useful chunks. Granted, you’ll have to find a way to integrate pumpkin into your dishes while you have it sitting there, but as long as you use an opened pumpkin within a week of cracking it, you’ll likely not have to deal with a squash going bad.

On “opening” pumpkins by the way, you should know that some of these squash varieties are tough. Like, tougher-than-your-knives, tough. Hubbard squashes, for example, were once used as foodstuff on sailing ships since they were thick-skinned enough to put up with rough voyages without going bad. Ma Ingalls had to take a hatchet to her Hubbards to get at their sweet, orange flesh. And I can personally vouch, she knew what she was doing. If a squash is too difficult to cut with a knife — and many of them are — you’ll need to bring out your inner pioneer and take a hatchet to them, or drop them onto a hard, clean surface. Though it sounds and looks brutal, it’s actually a lot safer than trying to force a kitchen knife into an unyielding squash on the countertop. Give your neighbors a friendly wave after you’re done, and hope they won’t spread too much gossip about your driveway cucurbit carnage.

Finally, if you do get a little pumpkined-out midwinter, remember that pumpkins are fantastic livestock food. Chickens and goats will happily help themselves to whatever extra squash you share with them. They’re full of vitamins that winter rations often lack, and the seeds are a good support in keeping them worm-free. In fact, you might plan on extending your winter feed by keeping a boatload of squash on the side, just for them.

How to Cook Rescued Pumpkins

When I rescued part of this year’s collection of pumpkins, I watched as the woman in line behind me curiously inspected my heaping cart. I anticipated her “What in the world are you doing with all those?” almost as the words were coming from her mouth. I get this question every year.

When I explained they were going into my winter larder, she shrugged. “So, you make a lot of pies or something? That’s … a lot of pies.”

I understand where this woman is coming from, but I’m not planning a pie fest (though some of these heirloom squashes do make positively decadent pies). The truth is, squash is such an amazingly versatile ingredient that constraining it to pies is missing its true potential. These various squashes all have their own unique flavors and textures. Some are stringy, some are custard-like, some taste very mild, and others have an amazingly sweet taste. You’re playing squash roulette with flavor. So, if you go out to save pumpkins from a dumpster fate, I recommend you get as diverse a collection as you can to give yourself the best chance at a broad palette of squash flavors.

On our homestead, we feast on rescued pumpkins all winter. Here’s a short list of our favorite ways to work these into nearly every meal.

Roasted Pumpkin

Sliced, skinned, and roasted at 400 degrees Fahrenheit until nicely caramelized and fork-tender. Though the ubiquitous cinnamon-clove-nutmeg spice combination pairs nicely with many pumpkins, try using curry powder, garam masala, ras al hanout, sage, Chinese Five-Spice, or smoked paprika for a different flavor experiment.

Pumpkin Puree

Slice, skin, cube, and simmer pumpkin until soft. Separate pumpkin cubes from water, then blitz in a blender until smooth. You now have an easy-to-use pumpkin puree that is far fresher and tastier than the tinny-tasting canned stuff. I use tons of this puree to make pies, pumpkin breakfast bread, and pumpkin muffins.

Pumpkin Puree Drink

Mix 1/2 cup of pumpkin puree with a cup of whole milk and ground spices of your choosing (cinnamon, nutmeg, and cardamom are always a win). Warm and sweeten, and thin with water (if wanted), and you have a really nice drink to sip by the woodstove.

Pumpkin Soup

Make a wonderful pumpkin soup. Simmer pumpkin cubes with onion and garlic. We spice ours with ginger, garlic, cumin, cayenne, turmeric, black pepper, and cinnamon, and then blend it smooth. Add optional cream, and top with sourdough croutons from yesterday’s bread baking, and you’ve got a filling, homemade meal.

Think of pumpkin as a vegetable. You can cube or slice it, and add it to curries and stir-fries as well. Serve with a side of rice, and you’ll wish you’d rescued every forlorn pumpkin at the store.

Pumpkin Seeds

The seeds are edible too! Depending on the variety, however, some may be too tough to chew. Once you’ve opened a big pumpkin, toast a sample batch of its seeds to see if you like them.

If the squash you’re using did require a hatchet, it’s likely you won’t be able to cut it into nice-looking chunks. That’s all right. Simply hack it into manageable slices or hunks, drizzle them with oil and salt, and roast them in the shell. Grunt like a cave dweller if it makes you feel better. The skin will become a handy little serving tool, and the flesh usually cooks down to a creamy texture that is delightful when topped with butter and scooped out, a spoonful at a time.

Enjoy Your Rescued Pumpkins

So get out there and join me in the great pumpkin rescue! There are literal tons of food in clearance bins, just waiting for someone to see their delicious worth. Give them a better use than merely rotting at the base of your front steps. Let them shine in the kitchen instead.

I’m in Queensland Australia, and grew up on a steady diet of boiled potatoes, pumpkin and whatever meat was available. Dad used to grow them to add to the diet of the farm animals too.

It wasn’t til I grew older that I discovered the joy of pumpkin scones (more moist and delicious than regular scones), pumpkin fruit cake and pumpkin soup.

I make the soup by simmering the pumpkin chunks with a small amount of water, chicken stock cubes and some fresh ginger. When the pumpkin is soft I blitz it with a stick blender and add a can of coconut milk. Any extra freezes well.

I add grated or thinly sliced raw pumpkin to soups and stews and it thickens everything a bit as it cooks. It adds nutrient too. If I have a lot of pumpkin I