Go to any cheap restaurant, and you’ll see a sorry showing of lettuce. It usually is represented in two forms: either a single leaf of romaine, apologetically separating your burger from the bun, or the translucent, colorless chunks of a sodden iceberg that makes up the bulk of the salad you regretfully got instead of the aforementioned burger.

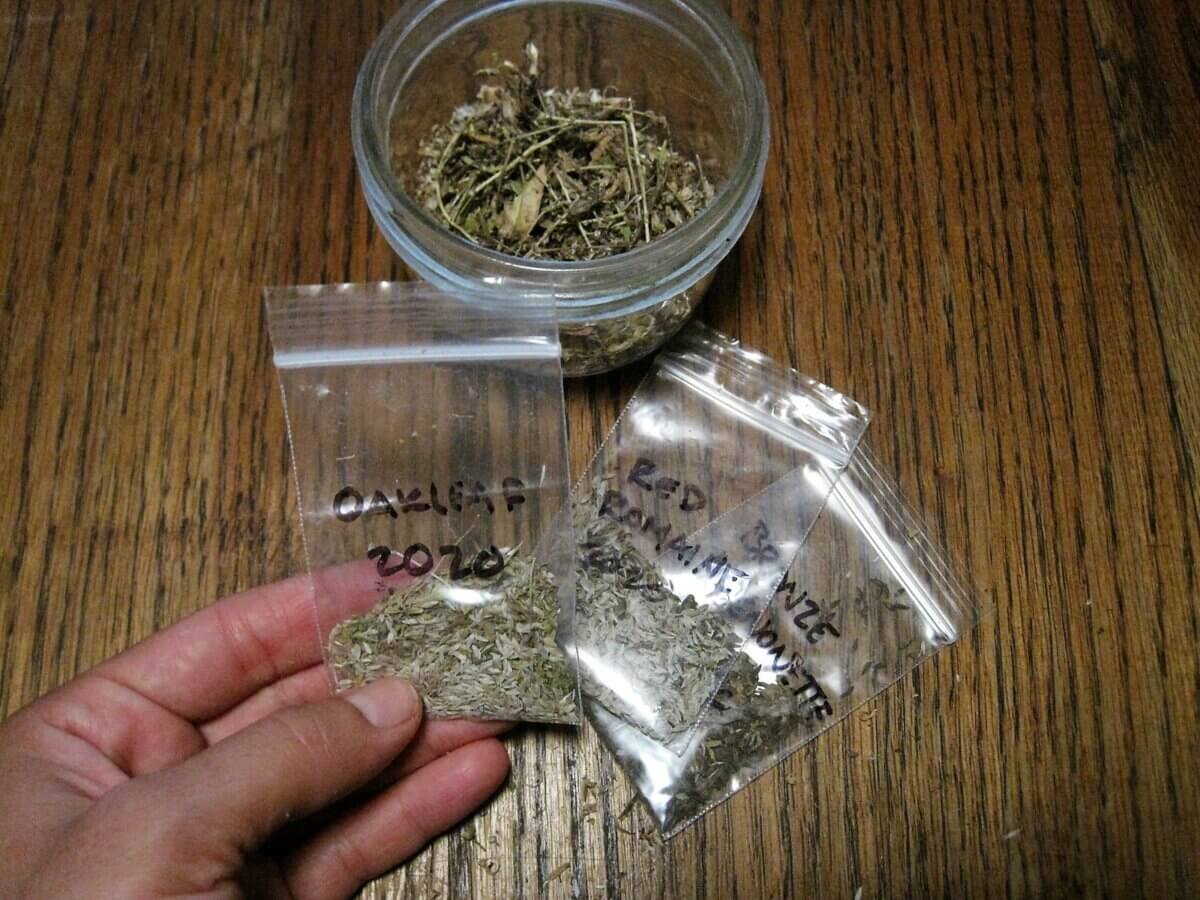

But those of us with gardens know that lettuce is far more than that. If you grow your own, you may be delighted with the sight of deeply-lobed Oakleaf, whimsically spotted Bronze Mignonette, wavy-edged Buttercrunch, or maroon-edged Devil Ear.

Planted early in the spring and fall for multiple harvests a year, easy to grow, and quick to harvest, lettuce is far more than a mere vector for ranch dressing.

If you’ve never grown lettuce before, you still have time to get it in the ground this fall, and harvest a handful of beautiful greens for the kitchen. When that time comes, this guide is here to offer you tips for harvesting lettuce with panache.

Harvesting Lettuce Leaves

Harvesting lettuce is pretty goof-proof. You can eat the leaves at any stage. The only real key to remember is to harvest lettuce in the morning before the sun’s heat has made the leaves limp and less juicy.

When you plant lettuce, you want to sow a little thicker than the packet recommends. As plants grow and begin to crowd, you can thin out the extras as delicious baby greens. Then, as lettuces leaf out, you have choices. Will you harvest the whole thing, or pick a few leaves at a time? Both are viable options.

How to Harvest Heads of Lettuce

For Crisphead and Butterhead varieties, you will probably want to wait until the plant has formed for a large, one-time harvest. When the head feels firm to the touch, it’s a good signal the time has arrived!

How to Harvest Romaine Lettuce

For Romaine and leaf varieties, you could also choose to pick the big outer leaves and let the inner leaves continue to develop for a surprisingly long time. Just be sure to work from the outside in — those tender, tiny, inner leaves are still full of potential growth.

Also, be sure to leave at least 4 to 6 six leaves at the center. The plant needs them to keep growing. Treated this way, some lettuce plants can produce a steady supply of leaves for weeks at a time.

When harvesting lettuce, whether cutting leaves or bringing in the whole plant, a sharp knife is a great tool. This will neatly slide underneath the head a few inches above the root to carefully slice individual leaves off the producing plant. A quick, clean slice keeps the plant from getting dirty and also allows plants that are continually harvested to quickly heal.

Harvesting Lettuce Seeds

An additional consideration when it comes to harvesting lettuce is whether or not you should be planting next year’s salads. If you have planted heirloom varieties of lettuce, you should plan on allowing some of your best plants to go to seed. This is not a difficult process as it merely involves letting your selected plants do their thing and hoping the heat doesn’t kill them before the seeds mature!

In my drought-prone, zone 6 garden, heirlooms doggedly send up their stalks and give me a bounty of seeds to harvest. Though bolting begins to reduce a lettuce plant’s productivity (it is putting all its energy into making a seed stalk, after all) it will repay you exponentially in future harvests. One seed will become hundreds.

Enjoy the cheery, daisy-like yellow flowers as they open, and then wait for the seed stalk to dry to a papery brown. This may take a surprisingly long time (as in weeks) so be patient. Once the fluffy seed heads have all started showing their silky down and the leaves have browned, clip the seed stalk from the plant. My messy-but-it-works method is to take each dry seed stalk indoors to my kitchen table.

Rubbing the stalk between my hands produces a fluffy mess. I like to pile the material in a mason jar and take it outside on a gently breezy day. Grabbing a pinch, holding it a few inches from the jar, and dropping it back in will clean the seeds from the rest of the material pretty well in a few minutes. Once the tiny, teardrop-shaped seeds are separated, I put them in labeled and dated jars or bags and save them for the fall and next spring’s growing.

You can store them in the freezer or in a dry, dark place. Though the freezer makes the seeds last longer and will also stratify them, I’ve had no problem planting unstratified, fresh-harvested, spring seeds in my fall garden.

If you are growing multiple varieties of lettuce, you don’t even really have to worry about cross-pollination Lettuce is self-pollinating and will rarely cross with other varieties.

Storing Lettuce

If you’re growing your own lettuce, you already know that the best lettuce is the stuff you harvested from the garden 10 minutes earlier. Cut leaves really don’t last long at room temperature. You can keep cut leaves fresher longer by storing them in a container or bag in the refrigerator. It will prolong their crispness for around a week, maybe.

Related Post: Growing Lettuce

If you really need to keep a large amount fresh for a longer time, try the same method used by those funny containers of “live lettuce” at the grocery store. Uproot the entire plant, and store it in the refrigerator with the roots in a container of water and a damp paper towel or plastic bag over the leaves.

Also, if you find that your fresh-harvested lettuce wilted between being picked and making it to the kitchen, don’t despair! You can revive those sad-looking leaves by floating them in a large bowl of icy water. If you get them in time, they’ll perk back up in about 15 minutes.

Preserving Lettuce

I know, I know. When it comes to the long-term preservation of vegetables, quick-to-wilt lettuce is probably the worst possible candidate. But believe it or not, I have two rather unconventional ways that keep your spring and fall lettuce haul around longer than the few days that picked leaves stay fresh in the fridge.

Though lettuce is the leaf supreme for fresh salads, this plant is surprisingly not just a one-trick pony. Lettuce is wonderfully tasty stir-fried with ginger, garlic and soy sauce or added to soups. These dishes can be cooked and frozen, and while it may not be the most instinctive way to use lettuce, it is a viable way to set aside a large harvest for later use.

Another way to use lettuce is not one I have personal experience with (yet), and a near-forgotten history waiting for someone to pick it up again. While thumbing through The Art of Fermentation by Sandor Katz, I came across a brief mention of salata (lettuce pickles) and lettuce kvass. Further research led me to a memoir by Gail Singer and Alexandra Grigorieva (which is free to read online).

The leaves were roughly torn, fermented, and sometimes blended with dill, sugar, and garlic before being served, but this process is basically unknown in modern culinary practice. The reason is the tradition of fermenting lettuce for food and drink comes from the shtetl culture of Ukraine which was all but annihilated.

The few survivors and descendants of the Yiddish families who once knew this way of using lettuce carried the memory to the present day. If any of you are adventurous fermenters, it’s well worth the experiment.

Even though lettuce is familiar to most of us, there’s still a lot to discover with this common plant. Enjoy it for fall. Maybe secret a few plants in a cold frame to extend the harvest, and dream of that first flush of early spring leaves once winter’s grip has weakened.

Leave a Reply