If you’re a new homesteader on new land, you’re in an interesting place.

You’ve probably just left everything in the city, your job, your friends, your family, your inherited way of life, to start over in the country. And, like earlier generations of back-to-the-landers, you may not really know what you are doing, have had no childhood training to bank on, and have relatively new “book knowledge” to guide you.

You’re going to make mistakes. You’re also going to watch other new homesteaders make mistakes, all based on your unfamiliar environments and unsteady choices. As you may soon understand, experience is a hard, very truthful teacher.

But once you have years of homesteading under your belt, and your neighbors have accepted you — and no longer refer to you as the “new arrivals” (other folks who have already come and gone will have received that dubious title) — you’ll look back on the past and see your initial, wobbly steps a little more clearly. You’ll wish you would have known then what you know now.

That said, I’d like to list the top eight new-homesteader mistakes that you might make, in hope this list full of advice and cautionary tales can help other greenhorns avoid some pitfalls that became obvious in retrospect.

1. Getting Too Many Animals Too Soon

I’ve read this story in several different forms, but most searingly, in a blog post from a couple of new homesteaders (I will leave the blog unnamed as a courtesy, of course). Immediately upon arriving at their run-down farm, the couple launched their livestock dreams, buying a herd of 5 bottle calves, 50 chickens, a pair of hogs, and no fewer than 10 sheep.

Never mind that they had no experience with farm animals or adequate structures prepared for them. They gleefully declared they were going to “fake it till they make it.” As you may expect, disaster soon followed their animal shopping spree. The demands of bottle-feeding calves sucked away their time while the dilapidated house desperately needed repairs. The chickens, largely fending for themselves without a strong coop, were slowly picked off by raccoons. Several of the sheep got foot rot while standing in their crammed, boggy paddock. Not sure what happened with the hogs — they never mentioned them again. All the while, this couple lamented their lot in life on their blog; claiming the hardship was burning them out, nothing was fair, and they never got a break. Eventually, a few years and many deaths later, they did get their feet under them and started caring better for the animals, but it came at quite a price.

Now, as tragic as they made the experience sound, the true tragedy was their mad rush to over-populate their farm, not knowing how to care for animals in the first place.

I know it’s the stuff of homesteader dreams to get that full passel of livestock, and envision the eggs, meat, and milk soon to fill the larder. But keeping farm animals is a different endeavor than keeping a dog or a cat, and it takes time to learn the ropes. Getting too many animals too soon is a recipe for death, disease, and disaster, guaranteed.

If you’ve never worked with livestock before, my recommendation to the homesteading newbie is to start off with a handful of chickens — somewhere around 5 to 6 hens — and nothing else. These birds will teach you the basics of animal care, feeding, and housing, and give you the chance to learn some homestead veterinary care as well. They’re inexpensive. If they get free, they’re not going to hurt anybody, they don’t require breeding to lay eggs, and the rewards are decently quick in coming.

Once you feel that chickens are no longer a huge project, and have become a part of everyday life (usually after at least a full year), I believe you can be ready to slowly expand your livestock endeavors. You’ll be a lot more ready for it!

2. Expecting Everyone Back at Home to Support and Understand You

As soon as you get off the beaten path of your peers and family, you’re likely going to go from “curiosity” to “forgotten weirdo” in surprisingly short order. Abandoning the pattern given you to live, along with the socioeconomic status and collar-color of those you once rubbed shoulders with, will not win you popularity points in the long run. You’ll have to get used to that.

To illustrate, let me point you to a curious, easy-to-gloss-over passage in the acknowledgments of “Restoration Agriculture” by Mark Shepard. For context, Shepard is a permaculture farmer and visionary who runs New Forest Farm, commercial scale, 106-acre, perennial agricultural ecosystem converted from what was formerly a dead, exhausted row crop grain farm:

“Thanks to Anna Lappe [a university presenter and activist] … an online recording of her giving a presentation to a group of college students where she mentioned New Forest Farm was the first time that I had ever heard anyone positively acknowledge the work that I have been doing [emphasis added].”

This guy had to have a thriving enterprise that was starting to attract attention from researchers, universities, and large-scale growers before he heard an encouraging word about his against-the-grain work. Plugging away at a vision and dream for years without anyone’s thumbs-up takes gallon of grit and a heck of a lot of contradictory confidence.

3. Expecting Anyone to Support and Understand You

Back-to-the-landers and their ilk have never really been well received on either side of the spectrum. Those they left behind in the city quickly forget them. And those country folk around them have seen too many homestead burnouts to immediately believe that they’ve got what it takes to succeed in their world. Get ready to feel a bit adrift for a while. It’s part of the process.

It can be tempting to start sharing your heart with the folks you meet as you potentially fight waves of loneliness. But I would advise lots of caution when it comes to sharing the guiding motivations, world views, and deep-seated rationales for your huge lifestyle change. These are precious things that you have worked hard (and probably sacrificed a lot) for. As such, only share them with folks that you have gotten to know well enough to trust. For example, you may have strong, valid opinions about free-range chickens on pasture, but if you preach at your neighbor with his crowded coop of Cornish crosses, you’re probably going to come across as an arrogant, baseless, know-it-all, and nothing will be accomplished (and a potential friendship may be lost).

Honestly, the same goes for expressing the political, religious, and philosophical reasons for why you do what you do. I’m not saying they’re not important, but you need to realize you’re already at a disadvantage as the local newcomer from the city, and it’s unlikely you’re going to find someone cut from the same cloth as you. It’s better that people know little about you, and get to know you slowly through your positive actions, than to be loaded up with a deluge of divisive factoids that will set them off without even shaking your hand.

It can feel isolating and lonely at first. Accept that. In time, as you visit farmer’s markets, talk to shopkeepers, help with community events, lend a hand to someone in need, and share extra tomatoes with your elderly neighbor, you’ll build up connections that will slowly erode away all your “newness.” And eventually, you will find someone that you can talk to.

4. Being a Crummy Neighbor

As I’ve already said, folks in the country don’t trust newcomers all that easily. However, now that I’ve lived out here for quite a few years, I can attest that their hesitation about former city-folk has its merits. The best way I know how to explain this phenomenon is in a set of bullet points about country neighbor faux-pas that are easy for a newbie to make and hard to live down. I’ve paraphrased these from Jackie Clay-Atkinson’s excellent article “Homestead Burnout — What It Is and How to Avoid It.”

Don’t Let Your Dogs Run Free and Unattended

No matter how much you like them, fact is, dogs can be destructive. They can kill a neighbor’s chickens and small livestock, and most country folks don’t give dogs a second chance when they’re discovered. There are too many stray dogs dropped off in the country to fend for themselves, so a trespassing canine is often met with a shotgun, not a query of where the owner might be.

Wandering Livestock Is a Big No-No

Granted, a one-time event is not an issue — it happens to the best of us. Many folks will work together to corral your wayward sheep or cow and make sure it gets back to you. But make a habit of it by not maintaining your fences, and you’ll quickly find that folks give you the side-eye rather than a friendly hello.

Don’t Endlessly Borrow Supplies

It’s one thing to ask a knowledgeable old neighbor to teach you the ropes of an unfamiliar tool — many of them are delighted for the chance to share their wisdom. But regularly borrowing tools or using up their goods, rather than buying your own, comes off as rude and irresponsible.

Don’t Complain and Gossip About Your Neighbors

Many of these folks are related to each other. Just let them do the talking and ask questions instead. You find out what you need to know.

Don’t Trespass, Hunt, or Fish on Your Neighbor’s Land Without Permission

You will only get away with it for so long (if you do at all).

Jackie sums up neighborly behavior nicely:

“In rural areas, you are judged first by how honest you are, and second by how hard a worker you are. If you are honest with your neighbors (pay when you say you will, help when you say you will, etc.) and as they see you are working hard on your new place, you’ll slowly move up in their eyes.”

5. Not Being Willing to Accept Death

This one might come across as calloused, but I’ve noticed a strange trend in the new-to-livestock conversations online. No one is willing, ever, to say that an animal died. They’ve “passed on,” “passed away,” “stopped fighting,” or “didn’t make it.” I’ve read more heart-wrenching accounts of a chicken’s death than I can count, and while my heart goes out to those folks facing it for the first time, the level of emotional turmoil is unhealthy.

The truth is, death is inevitable on the homestead, when animals are involved. Predators have no compunctions about killing off an entire coop of “featherbabies.” Runts will die, even if you nurse them through the night. Sometimes, an animal’s suffering is so great due to illness or injury that the most kind, humane thing you can do is to put them down. And for those of us looking to raise our own meat, rather than depending on a CAFO (concentrated animal feeding operation) to do it for us, death is the necessary gateway between paddock and dinner plate.

I wrote a whole article on dealing with death on the homestead to explain this one further, but I’d like to supplement it with a realistic quote from long-time homesteader and writer Gene Logsdon: “We raise our farm animals with loving care, grow quite fond of them, put our lives at risk to save theirs if necessary, and then we kill and eat them.” That’s the sort of reality you’ll be dealing with.

As a subtopic, I’d like to add what I consider the mistake of naming all your animals. I know this is a touchy one, but naming animals will almost always make the killing, culling, or butchering of them more difficult.

Of course, animals do need to be individualized so that you know which one you’re talking about, but you might try referring to their color, size, or breed, instead. It doesn’t dehumanize them (they’re not humans in the first place), and it certainly doesn’t change how you treat them. But it is a lot easier, more truthful, and more mentally healthy to say “we butchered the red hen yesterday” than to shakily admit “we finally sent poor Mrs. Fluffinstuff to freezercamp.” I truly believe it’s healthier for homestead kids as well. Teach them from the get-go which of your animals are going to be meat, and don’t pad the butchering process as some faraway, mystical boogeyman. If prepared, and given the chance to ask all their questions, kids exposed to the processing of their own food develop a huge respect and understanding of the process.

6. Trusting in Everything “The Books” Say

When you don’t know anything about livestock, foraging, gardening, or homesteading, books are authorities to be studied, memorized, and trusted. But once you start living this lifestyle, you’ll come to a strange realization: Many book authors — particularly modern ones — don’t always know what they’re talking about. You’ll have to come to grips with figuring out what you trust more. Your eyes and the words of your neighbors who have done it for years, or the printed page that may or may not have had an editor who knew how to fact-check the information.

This isn’t to say that books are useless. Far from it! Lacking grandparents and a cultural background to guide you, books are a huge resource of knowledge and wisdom that we just can’t get anywhere else. But your experience will become an increasingly trustworthy guide that will help you discern when the book may not be exactly what you need to solve the personal challenges your land offers. Books often describe an accepted, conventional method that works — but as you will find out, there are many other solutions that can work just as well, or better. You may have to innovate on your own, however.

The same goes for websites, magazines, and videos online. Just because someone says it with conviction doesn’t mean that it’s the best fit for you, your animals, or your land.

7. Pedantically Expecting to Live the Same Way in the Country as You Did in the City

We have an acquaintance who was also seeking to get off the grid and bought some property near us. Watching his process has been interesting, to say the least. Absolutely disinclined to experience discomfort, he has spared no expense in buying the most expensive composting toilet system he could find, a super high-end woodstove, and a huge array of off-grid gadgets that he read about in his favorite magazine.

He said he doesn’t like chainsaws and doesn’t want to buy one, so he has asked a contractor to clear his woodlot with machines and has made additional purchases for cords and cords of firewood from elsewhere. He told us he doesn’t like dealing with rainwater catchment since he doesn’t know much about it, so he has contracted out to dig a new well that’s already run him a 4-figure bill.

Now, before you think I’m ragging on another person’s style like I’m some sort of homesteading authority, hear me out. This is a cautionary tale. This acquaintance is starting to run out of money and patience with his recent purchases and lifestyle changes. He wants to have all the benefits that he believes come from living off the grid, but he still wants to have high-speed internet, a warm house in the winter morning, and all the amenities that he was used to from living in the city. He complains about having to drive a far distance to get to the bar when it used to be close at hand. He is frustrated with having to clear land for his planned inground pool and somehow figure out how to get the water to fill it. He isn’t willing to learn from his neighbors or from us, because he said he read a website once and knows what he’s doing.

It’s an extreme case, but I think the moral is clear. If you choose to homestead or live off-grid, there’s got to be a lifestyle change that accompanies the location change, or you’re going to be living in perpetual frustration, disappointment, and eventual burnout. And I find it a real shame because this life is full of joy, freedom, and purpose — if you’re willing to change your expectations and perceptions. I truly do hope that this acquaintance makes it through this winter a lot wiser and more humble, but honestly, only time will tell.

8. Setting Unrealistic Goals

“We’re moving to the country!” a fresh-faced new homesteader exclaims. “We’re going to grow all our own food, sew our own clothes, make soap, raise horses to ride and raise geese and chickens for meat, and we’re going to build our own house and furniture and start up a farmer’s market to sell all our extra produce. And we’re going to do it all off-the-grid. It’s going to be a wonderful adventure.”

And yes, that is truly a wonderful adventure to set out to achieve. But if you think you’re going to do all of that in your first year, I’ll just say it bluntly: You’re not. Nothing can lead to homestead burnout and blunder more than starting too many projects and endeavors all at once and not giving yourself time to learn, adjust, and grow. This is a lot, and I mean, A LOT of work, and us modern folks have quite the disadvantage. Most of us are learning how to do it as adults, rather than training for this lifestyle from childhood. Even if you have your whole family on board, there are going to be really big challenges, hard days, and sometimes, few immediate payoffs.

Give yourself your best chance by learning how to set realistic goals and pace yourself in achieving them. I can’t tell you what that looks like, as it’s an incredibly personal process intimately tied to your specific goals, land, and philosophy. But I can offer a model. Sit down with your homesteading cohorts, if you have them, and list out every single goal you have for your endeavors. Cut them into strips or put them onto notecards — one goal per piece. Then, take as long as you need to arrange those goals in order of importance. Figure out what goals need to be achieved immediately, which ones can wait a few months or years, and which are desirable, but not absolutely crucial. Find out what goals hinge on other goals being accomplished first.

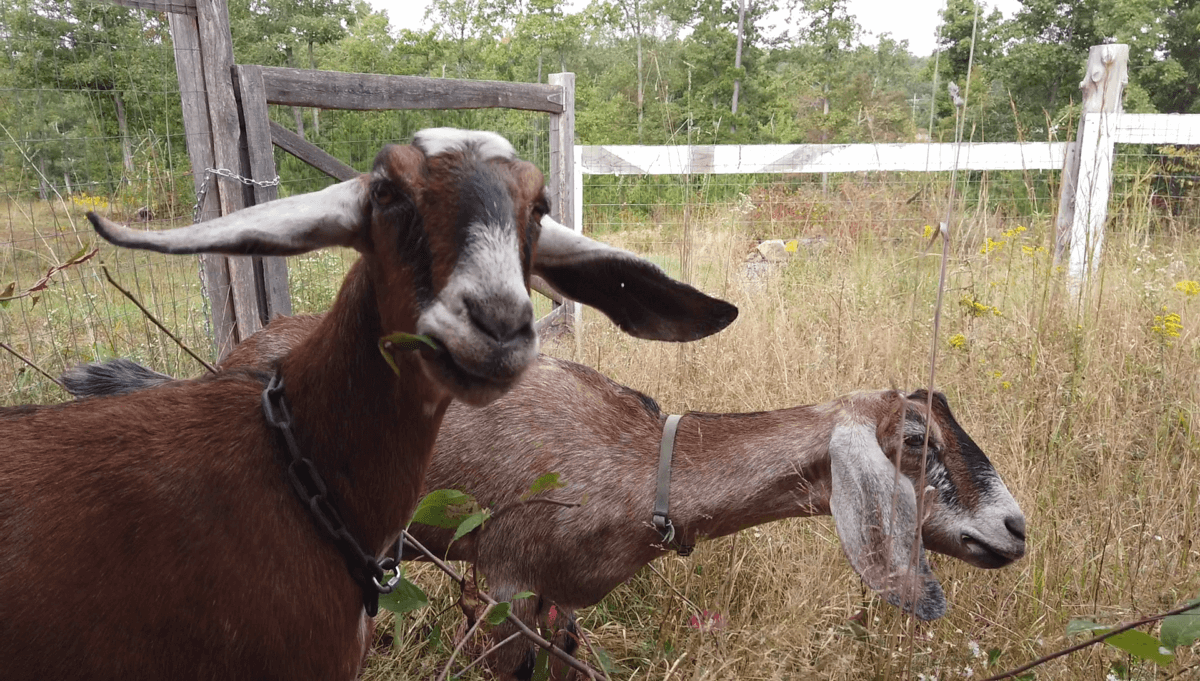

Though this process is simple, it may help you organize your thoughts in a way that helps you prioritize your projects. Fixing the broken-down house is a whole lot more important than raising five bottle calves. Getting rainwater catchment set up now will at least give you a somewhat reliable source of water that can buy you time until the new well is dug. Taking a full year to enclose the pasture with a better, fixed-up fence is worth the wait before you bring home the milking goats. Establishing a 100 by 100-foot garden is actually a huge endeavor. Maybe go for 15 by 5 feet and see if you can keep up with that first. You see where I’m going with this.

So, if you’ve kept with me for this whole, long article, I hope you don’t come out of it discouraged. There are inevitable mistakes awaiting anyone who decides to take a plunge and try something new. But if you plan ahead, pace yourself, and give yourself time to learn from both the failures and successes, you may get through those bumpy newbie years with a fistful of stories, a coop full of chickens, and the growing satisfaction of a life well lived. And maybe these bits of advice can keep you from repeating some of the mistakes the rest of us have made.

Leave a Reply