One of my favorite college coffeehouses was across the street from a milling company. I spent many hours sketching and sipping their various brews, the mood-lit ambiance of the cafe constantly underscored by the low hum of unseen machines turning grain into flour. Anyone who parked more than an hour on the that street would inevitably come back to a car lightly dusted with fine flour — made airborne by the sheer volume of wheat processed there.

The grain mill had a sort of mysteriousness. It was tall, imposing, and inaccessible to non-employees. But the act of milling grain into flour need not be some hidden process locked behind a set of industrial doors. For millennia, this most basic of tasks took place in the home, and it still has a place in it. The sound of grain being milled for daily bread can be a pleasant underscore to your own tea and coffee-sipping.

Have you ever thought about grinding your own grain? Would you like to step up your bread game to the ultimate level of customization and nutrition? Are you interested in benefiting from the many benefits of fresh ground, non-rancid flour? To mix-and-match your own grain blends? Let’s chat and learn more about how to make flour.

Watch The Video

How To Grind Your Own Flour

Grinding your own flour requires a little bit of investment at the beginning, but it more than pays for itself in the end. Wheat is a fairly cheap grain to buy, but the food it can make is both nourishing and filling. You can take the production of your daily bread back into your own hands with a few simple steps and tools. The quality of your homemade bread will be far superior to store-bought, and for a fraction of the price.

1. Find Your Whole Grains For Grinding

The first step to grinding your own flour is getting the whole grains to grind. I recommend organic grains to avoid the toxic glyphosate that is sprayed on conventionally-ripened grains. Think they’re impossible to find if you don’t grow them yourself? Not so with the service offered by Azure Standard.

This awesome company is a neat opportunity — particularly for rural homesteaders with few store options — that lets you go online, order bulk goods, and go to a nearby pick-up location to collect your precious haul. Can’t find a drop point close enough to your home? With a little community coordination, you can contact Azure to set up a new one in your area.

2. Prepare A Food-Safe Place To Store Grains

The next step of flour production is having a safe place to store all that grain. Food-grade, 5-gallon buckets with a Gamma Seal lid are an excellent way to keep mice, bugs, and moisture from spoiling your food. Be sure to clearly label the buckets with the date and contents to keep things neat and orderly. Contained safely, you can store your buckets in a garage or basement until needed.

3. Invest In Your Mill And Start Grinding Your Grain

Next, you need to somehow pulverize the grains into flour for your baking and cooking. There is a wide array of manual and automated grain mills available for your perusal. If you want the convenience of having mechanically-ground flour, the highly-rated WonderMill may be your style.

For those who don’t mind a bit of a workout and want to grind flour off the grid, a manual mill with a flywheel like the Country Living Mill is an excellent choice for long-term flour production. Don’t let the price of the new mill turn you off. Many barely-used mills are available on sites like eBay or Craigslist for far more affordable prices.

Being your own miller gives you the opportunity to mix-and-match your flour blends at will. Additionally, you can adjust the range of fineness for the grind to whatever you’d like. Want a coarsely-ground porridge blend? The finest of flours for a tender pie crust? A multigrain blend for some hearty rolls? The flour world is now yours!

If you’re going to go through the trouble of taking over your own flour production, keep one key in mind. Flour (particularly whole grain flour) can go rancid in as little as five days. Though it will require a little preplanning (not a bad thing), you’ll be best served by grinding only the flour you need for a project — and really understand the meaning of “daily grind.”

Grains To Grind

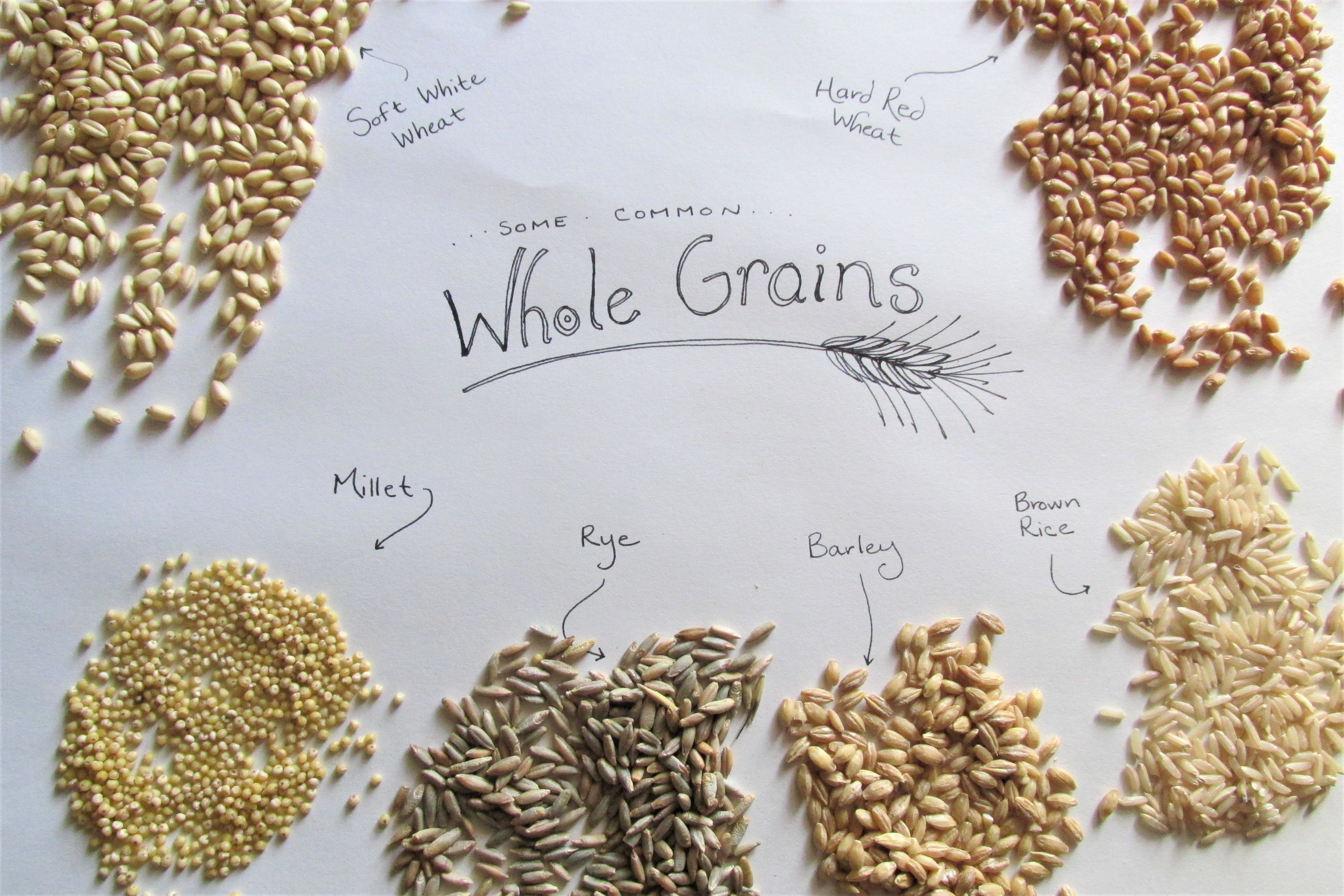

Rye, barley, oats, and wheat are all traditional cereal grains with a long history of being ground into flour and used to make bread. You should experiment with all of them. Every grain offers its own style and texture. But of the lot, wheat is probably the most familiar to the beginning flour miller.

As soon as you start to buy in bulk, you’ll realize that wheat is complicated. This versatile grain has been grown and developed for so long, and by so many cultures, that it has taken many specialized forms. There are three aspects used to label wheat grains, and knowing these classifications will help you make the best bread and bakery. Wheat is classified according to its hardness (hard or soft), the season in which it was harvested (spring or winter), and its color (white or red).

Here are some ways to understand the differences these varieties create.

- All hard wheats have a higher protein content than soft wheats, meaning they will form more gluten strands and make a stronger-structured dough.

- White wheats will have less of those proteins than red and have a different flavor. They are varieties of wheat that have had the color bred out of them. This apparently makes the flavor milder — though to be honest, I’ve never noticed the difference.

- Spring wheats will have more protein than winter wheats, and winter wheats are usually higher in minerals.

Does it make sense or sound like the setup to an SAT question? Don’t fret! Basically, think of it this way. The higher the protein, the more gluten can be developed and the more extensible the dough can be — good for yeasted bread or pasta doughs that need to allow for the formation of air bubbles and hold together well. The lower the protein, the more delicate the dough will be — good for sweets and biscuits. Make your choices accordingly.

Related Post: 11 Healthy Grains You Should Add To Your Diet

Other grains and seeds-used-as-grains are millet, corn, spelt, kamut, quinoa, amaranth, teff, emmer, buckwheat, sorghum, and leached acorns … once you start getting interested in making and blending your own whole grain and home ground flours, it’s a delightfully slippery slope.

Some Flour Mix Ideas From Our Homestead

If you’re thinking you’ll need some recipes to use up your homemade flour, consider these ideas from our own homestead.

Multigrain Breakfast Porridge

Coarsely grind 2-parts hard red wheat, 1-part barley, 1-part rye, 1-part millet, ½-part rice, and 2 tablespoons of flax. The night before, soak the amount you’ll need for breakfast in water. It will make the nutrients more available and the porridge will cook much faster.

For one serving, boil 1 ⅓ cups of filtered water with a dash of salt. Mix in ½ cup of porridge mixture, stirring to avoid clumps. Simmer for 10 to 20 minutes, stirring to keep it from sticking to the bottom and adding water as necessary for desired consistency. Serve with butter and maple syrup drizzled on top.

Gluten-Free Breakfast Porridge

Coarsely grind equal parts oats, millet, and rice. Soak ½ cup of the mixture overnight (as with the porridge above). For one serving, boil a cup of filtered water mixed with a dash of salt, a dash of nutmeg, one mashed banana, and 2 tablespoons grated coconut. Slowly add to porridge mixture while stirring to avoid clumps. Simmer for 10 to 15 minutes, adding more water as necessary to achieve desired consistency.

Sourdough Bread Mix

My favorite flour blend for making our daily bread is a mix of 3-parts hard red wheat to 1-part rye. The hard red wheat is ideal for bread, as its high protein content allows for good gluten development, and the rye handily absorbs water for a delightfully chewy crumb.

With the long rise required for fermentation, you can play with the texture of the flour — grinding most of it at medium-fine but letting the remainder be coarse like the porridge mixture. The result is a hearty, toothsome loaf that will satisfy.

Related Post: How To Capture And Use Wild Yeast

This mix, when ground as finely as you can manage, also makes a pliable but strong dumpling dough. It holds up well for cooking delicious perogies, making whole-wheat pasta, or steaming whole-wheat Chinese dumplings.

Cookie, Biscuit, Pie Crust, And Brownie Flour

Unlike my bread mix, I opt for soft white wheat for most of my pan-based or sweet baking. These pearly grains grind much softer and more finely which makes a more delicate crumb for sweets. Additionally, the lower protein content of soft, white wheat doesn’t form strong gluten strands — frustrating to use for bread or dumplings, but fabulous for pancakes, waffles, muffins, and flaky biscuits.

Benefits Of Grinding Your Own Flour

Grinding your own flour is a major step toward long-term health and self-sufficiency.

Homemade Ground Flour Is Fresher

First, there is the freshness factor. There’s no way to know how old the flour in the store is, but you can be sure that unless it is ground on site and refrigerated, it is not the freshest.

Just-ground flour is a totally different material than stale, store-bought flour. It’s rich-smelling, full of beneficial oils, and much better tasting. You can actually smell the difference. Breathe in the aroma of a handful of hard red wheat berries, and it smells like sweet graham crackers. Flour from a bag smells like its packaging.

Fresh-Ground Flour Is Customizable

Second, there’s the flexibility. Being able to have flour however you want, whenever you want, in the quantity you want, is a huge culinary advantage. The quality and range of your kitchen’s food production has the potential to skyrocket with this simple change.

It Reduces Your Waste

Thirdly, grinding your own flour reduces the waste produced by your house. The only packaging in the process is the 25 to 50-pound bags used to bulk transport grain. These bags are reusable and recyclable and can be used for tons of different purposes on the homestead.

Homemade Flour Is Better for You

Fourthly (and most important), there’s the nutrition factor. In my perspective, this is the most important benefit. Whole-grain flours are vastly superior to refined, bleached white flour.

“With its full complement of vitamins, minerals, soluble and insoluble fiber, antioxidants, and other beneficial phytochemicals, the whole-grain bread naturally provides nutrients that, day-to-day, protect against diseases that have become chronic in modern society: diabetes, several cancers, diverticular disease, and cardiovascular problems.

Bread made from whole wheat provides significant amounts of essential minerals — iron, zinc, magnesium, manganese, selenium, and some calcium … Recent research shows that dough fermentation unlocks minerals from acid bonds.”

–Alan Scott, The Bread Builders

Making the switch to eating real, fresh whole-grain flour can make drastic health benefits in your life. This leads me to my next point …

Why White Flour Should Be Thrown To The Curb For Good

White flour is an ancient luxury turned false modern necessity. To this very opinionated homesteader, the process of turning nutrition-packed whole grains into a bland, fluffy-white powder is absolutely unnecessary, tragic, and wasteful.

The historical precedent for white flour was elitist in nature. In both ancient Egypt and Europe where wheat was a staple, white flour became a status symbol. The time-consuming, multiple rounds of fine grinding and bran sifting required to make a white product were something that hard-working peasants and normal folk didn’t have time to do.

The rich could pay others to do the work for them which made white flour purely an upper-class luxury. The irony of this practice was that the elites were exchanging health for social standing. Many of the dietary ills of the rich were due to poor nutrition that could have been solved with eating the fermented whole-grain bread that sustained lower class farmers.

Related Post: 25 Delicious Sourdough Recipes For Your Home Starter

In modern times, the decadence of the rich has become accessible to the rest of us … and with it comes the corresponding wastefulness and disease. The process of making white flour has become a scientific art form in nutrient depletion. In order to reduce whole grains into white flour, they need to go through a huge and dramatic transformation that makes the sifting of 300 years ago seem simple.

First, the whole grains are put through an industrial roller mill. Rollers spinning at different speeds squeeze the grains into progressively finer powders. As the grain passes from roller to roller, the bran (the outer layer of the kernel) and the germ (the inner embryo that contains the majority of the oils) are sifted out — leaving behind mostly starchy endosperm. Some older mills also heat the flour due to the friction of the rollers, inactivating many of the vitamins left in the grains.

By this point, about 72% of the individual wheat kernel is left. This material is intentionally oxidized. In big mills, this is usually done chemically by bleaching the flour, and then adding latent oxidizers that continue the work during kneading and baking. This makes the flour easier to be mechanically worked into dough on a large scale, and eliminates the need for fermentation. Of course, for the sake of convenience, this wheat-based product now contains oxidized fats and traces of many chemical bleaching agents used to whiten the grain.

Enriched flour is even more of an insult to the original grains. As the population historically suffered from beriberi and pellagra on their refined-flour diet, government authorities have been forced to recognize the inherent nutritional deficiencies in white flour and its products. As a result, artificially-created mimics of several vitamins and minerals that had been stripped from the whole grains during refinement, are sprayed back on the white flour before it is packaged.

Personally, I will never advocate for the use of white flour. Ever. Devoid of nutrition, chemically altered for artificial appearances, and generally just bad for you, white flour is a refined shadow of the real food that whole grains — particularly fermented whole grains — offer your body.

If you care about your body, you’ll eventually have to confront this white flour dilemma. On one hand, white flour is an incredibly refined product, and produces textures that people have come to hold dear. White flour sourdough, for example, rises higher and has a lighter crumb than any whole-wheat bread could ever achieve. But who said that a light crumb and high rise had to be the pinnacle of bread experience? Maybe it’s time for a paradigm shift.

The fact is, if you decide to grind your own flour, you will be choosing wholesomeness over nostalgic presentation in many circumstances. While your body will benefit, your mind may need to do some work to accept the results of your whole-grain bakery.

You won’t have pillow-soft dinner rolls or pure white sugar cookies with whole-grain flour. But you will have better-tasting bakery and better health. While you decide what’s more worthwhile, I’ll give you these two quotes to consider …

“Since World War II, the food industry in the U.S. has gone a long way toward ensuring that their customers … do not have to chew breakfast. The bleached, gassed, and colored remnants of life-giving grains are roasted, toasted, frosted with sugar, embalmed with chemical preservatives, and stuffed into a box much larger than its contents. Fantastic amounts of energy are wasted by sales and advertising departments to sell these half-empty boxes of dead food …”

William Duffy, Sugar Blues

“Modern commerce has deliberately robbed some of nature’s food of much of their body-building material while retaining the hunger satisfying energy factors. For example, in the production of refined white flour approximately eighty percent or four-fifths of the phosphorous and calcium content are usually removed, together with the vitamins and minerals provided in the embryo or germ. The evidence indicates that a very important factor in the lowering of reproductive efficiency of womanhood is directly related to the removal of vitamin E in the processing of wheat. The germ of wheat is our most readily available source of that vitamin. Its role as a nutritive factor for the pituitary gland in the base of the brain, which largely controls growth and organ function, apparently is important in determining the production of mental types. Similarly, the removal of vitamin B with the embryo of the wheat, together with its oxidation after processing, results in depletion of body-building activators.”

Weston Price DDS, Nutrition and Physical Degeneration

Historical Ways Flour Has Been Milled

Pressing a button on your mechanical flour mill and passively producing all the flour you want, is the stuff of ancient women’s daydreams. Historically, much of their time was spent manually processing whole grains into flour that could then be soaked, fermented, and baked into the day’s main meal.

It was quite the endeavor! From beating grains with a rock to using the power of the sea, innovative ways to accomplish this daily task have been imagined and built the world over. Here’s a sampling of historical ways that grains have been turned into the staff of life.

Mano And Metate

Smashing grains into flour with two rocks sounds basic, but these ancient tools were very carefully selected and crafted. The mano — a smooth, round rock that fit in the hands — needed the right density and heft.

The metate — a curved, plate-like base against which the grains were ground — needed to be as hard a stone as could be found to avoid too much grit being worn off into the food. Many cultures around the world have some ancient variation on this theme.

Quern

A quern is a simple hand mill that can be powered by a single person. A stick placed into a strategic hole in the top millstone, allowed the miller to turn the stone against a fixed bottom stone and produce flour.

Plumping Mill

The plumping mill is probably the first automated mill. It could be set to pound a measure of grain on its own while the miller went about other tasks. Usually set alongside a water wheel, the plumping mill was essentially a big hammer with a sloped bucket on the handle.

Grain was put in a mortar beneath the heavy hammer, and water was allowed to flow into the bucket. The water’s weight raised the hammer, was poured out, and WHAP! The grains were pounded, blow-by-blow until they were flour.

Water Mill

Many of us have seen water wheels as some picturesque background in a country calendar, but these river-powered wheels were used to harness the energy in a river’s current and do jobs from sawing lumber to grinding grain. A surprisingly complex series of flues and gears were employed to translate flowing water into the power to move giant millstones against each other.

A fascinating variation of the water mill is the wave mill used on the British coast. Rather than a river’s current, the incoming and outgoing tide was used to power the mechanics.

Wind Mill

Not just for battles with Don Quixote and Rocinante, the windmill harnesses the power of air currents to move its giant gears and millstones. Many people don’t realize that these sail-topped towers can be rotated to catch the breezes as they change direction, or that they can be shut off during harsh storms to prevent them from milling uncontrollably.

These mills are somewhat terrifyingly powerful in a gale. There are many stories of ancient millers falling into the noisily humming works and meeting a grisly end.

Animal-Powered Mill

Ancient Romans are often credited for coming up with large-scale stone milling; they copied and improved upon a Greek design and started milling flour with donkey or ox-power. Eventually, they converted to water power with impressive feats of engineering.

How would I grind Graham flour at home. I know that it has two different textures in it