The first time I met a mulberry, it was a confusing introduction. At the time, I considered my general plant knowledge to be better than average, but somehow, this unfamiliar tree didn’t make sense.

It was a beautifully shaped, open grown tree with scalloped alternate leaves that I couldn’t identify offhand (because mulberry trees come in several different shapes). I knew sassafras had three leaf shapes, but this tree clearly wasn’t sassafras. And, weirdest of all, it was positively dripping with a bounty of berries that for all the world, looked like blackberries. But a full-on blackberry tree? That couldn’t be right.

Watch The Video

The flocks of robins and woodpeckers flitting through the branches, however, knew what I didn’t at the time. They understood that the abundance offered by these common trees is something to eat, not gawk at. When I sampled my first mulberry that day, I was shocked by the sweet, vanilla-honey-berry flavor. With berries on the brain, I started seeing mulberry trees everywhere that summer — along city sidewalks, country lanes, and park avenues, and below them the ground was carpeted with free fruit.

How did I make it all the way to my 20s and never taste a mulberry? No idea, but I’ve done my best to make up for it in the years that followed that summer afternoon. These sweet, warm-weather treats have since become one of my favorite wild fruits, and if you’ve made it this far in life without gathering an ample handful of finger-staining goodness, I hope to help you rectify that error.

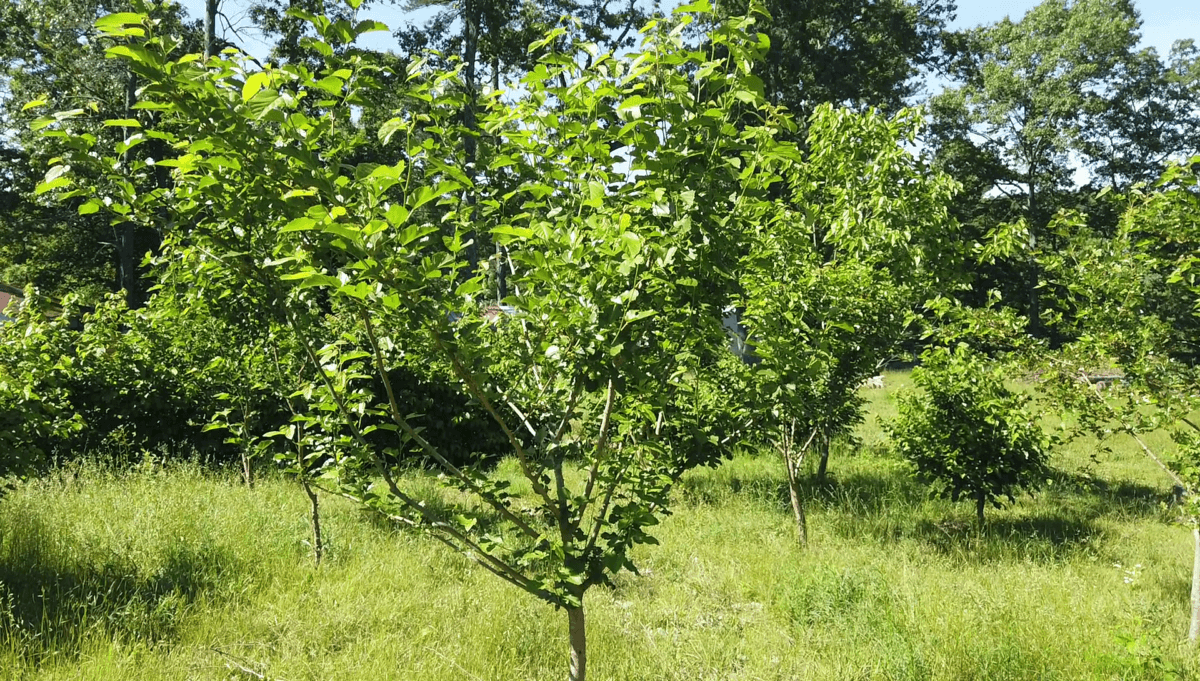

Finding and Identifying Mulberries

There are four species of mulberry in the United States: some native, some introduced, all edible.

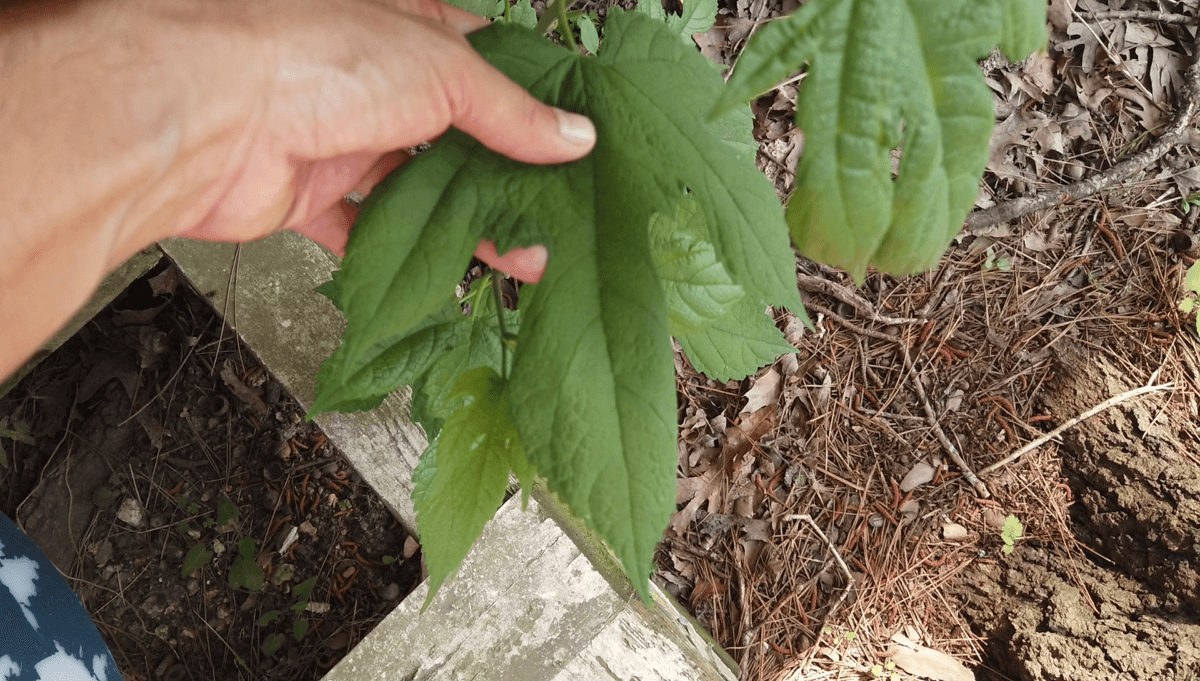

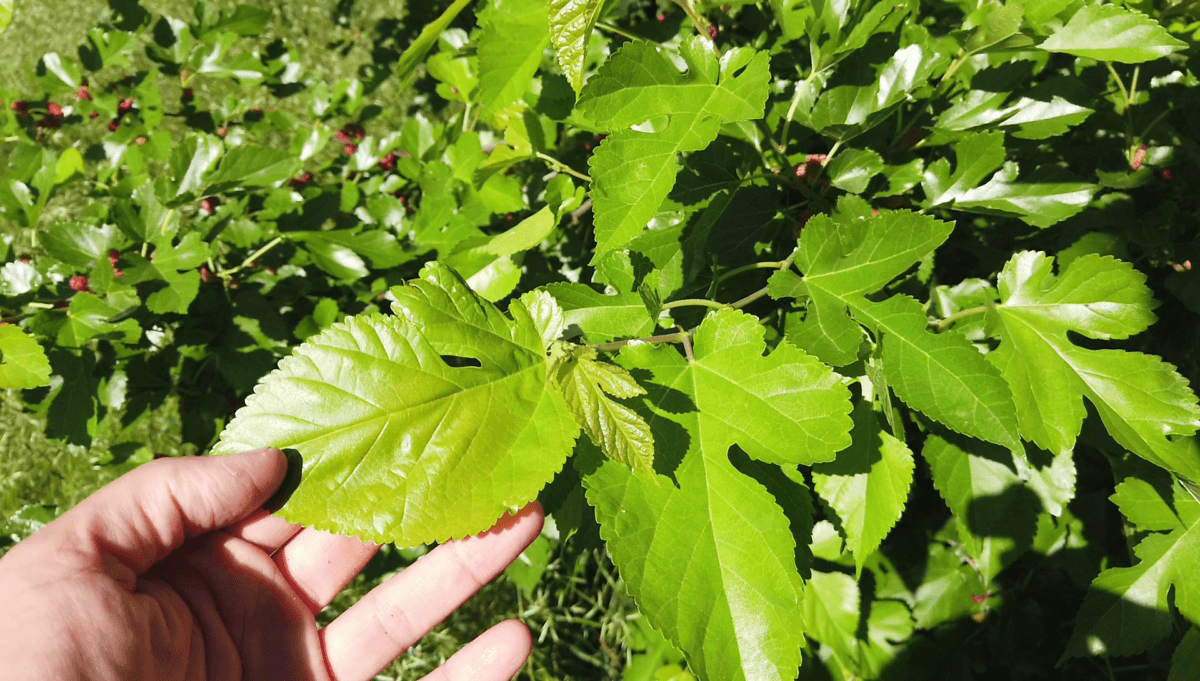

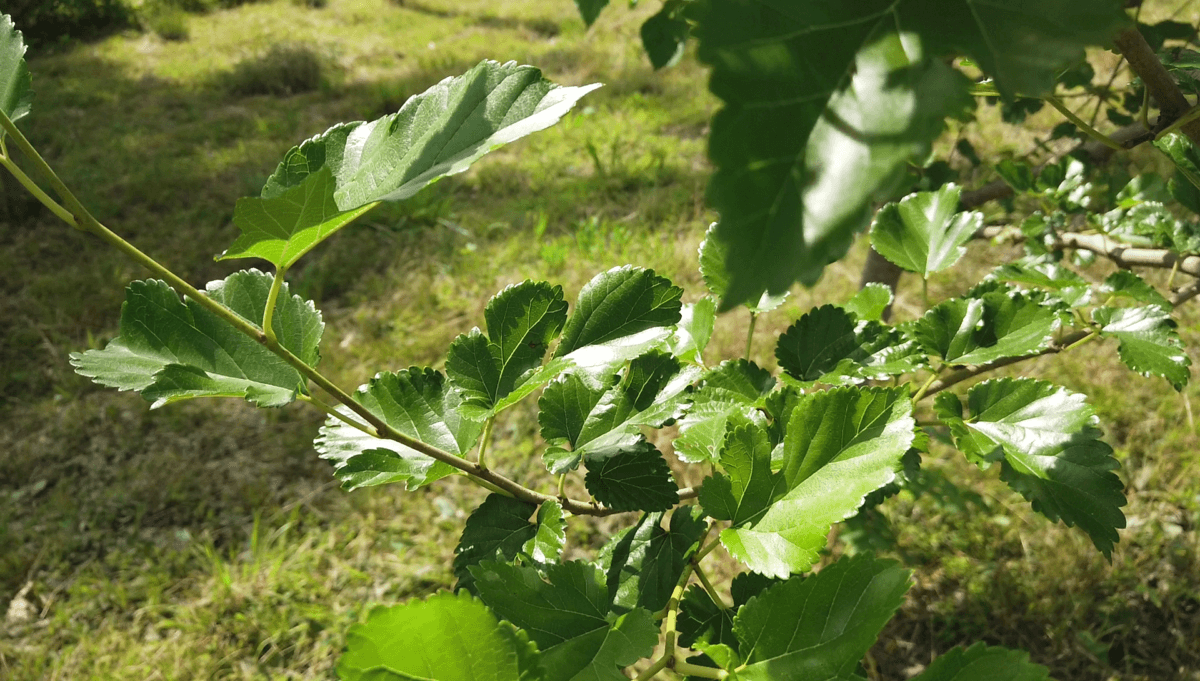

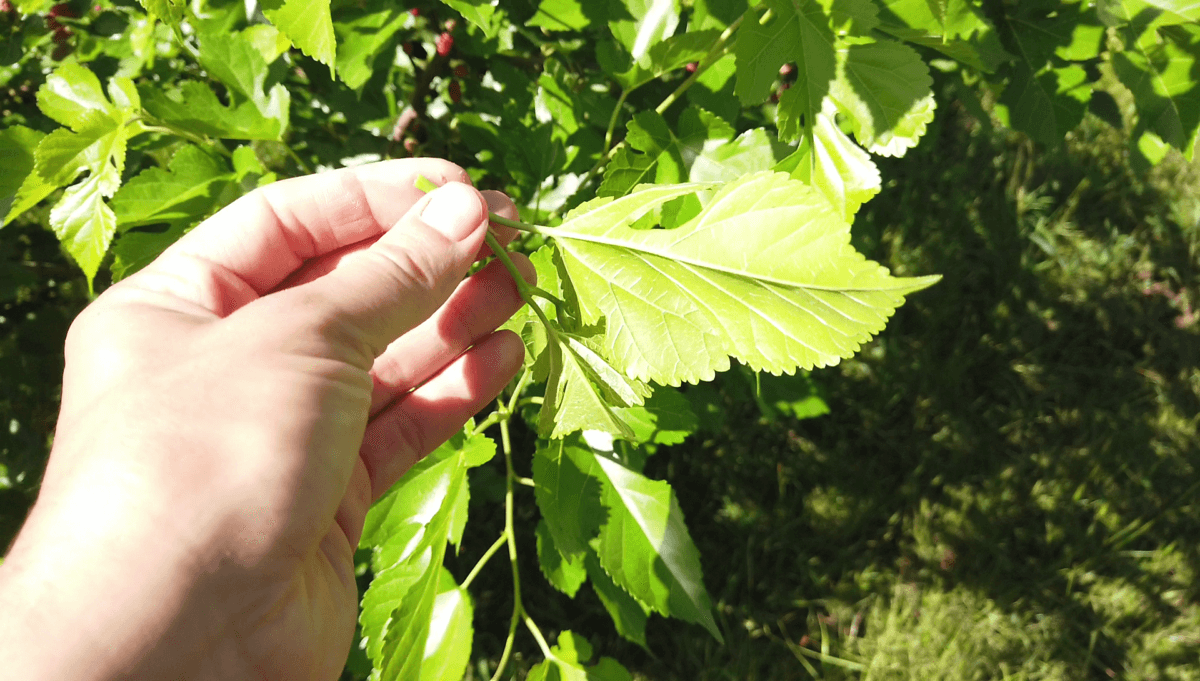

As you’ll soon discover, mulberry leaves, while distinctive to the genus, are anything but consistent. They’re scalloped, sometimes lobed, and sometimes entire. They have a family resemblance, however, and so the best advice I have is to get out there and find as many mulberry trees as you can. The more you observe them in person, the more you’ll recognize them in all their weird and wacky shapes.

Morus nigra is an introduced species found scattered across the lower portion of the country, but it is relatively rare. Morus microphylla, the Texas mulberry, is a native tree constrained to parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. I’ve never encountered these two species and won’t be featuring them in this article, but everything I say about mulberries applies to them if you happen to have access.

The real food haul is to be found with Morus alba and Morus rubra, the two species that carpet the land from coast-to-coast. If you encounter a mulberry tree, it’s very likely one of these two.

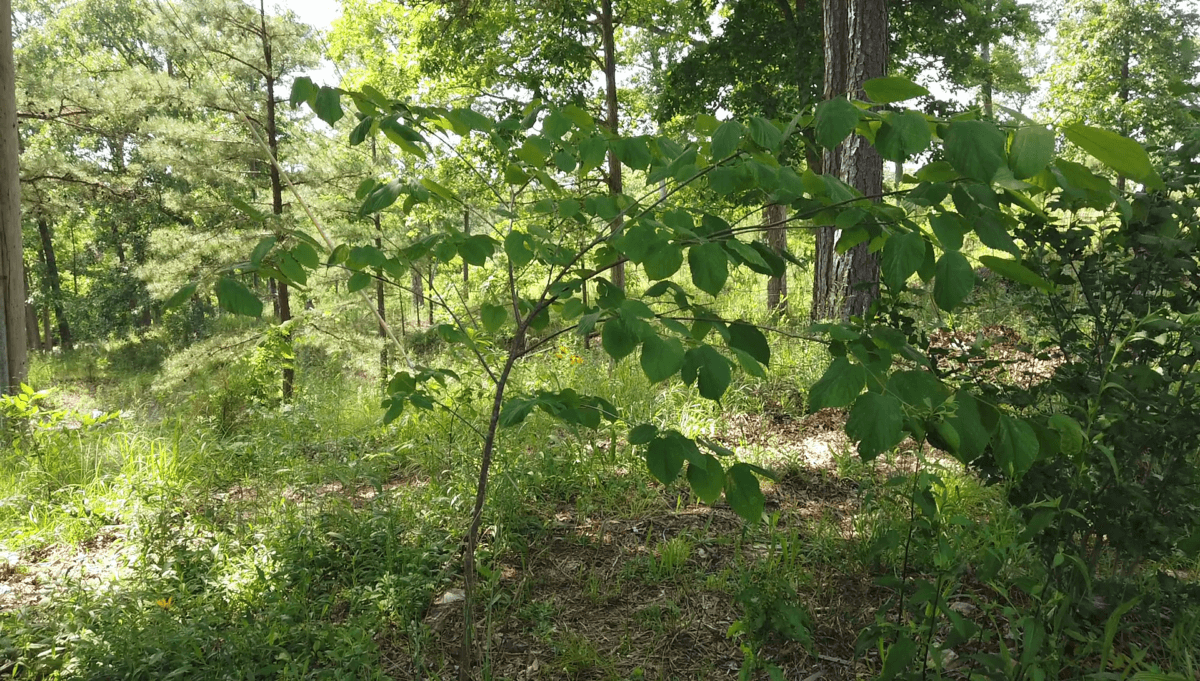

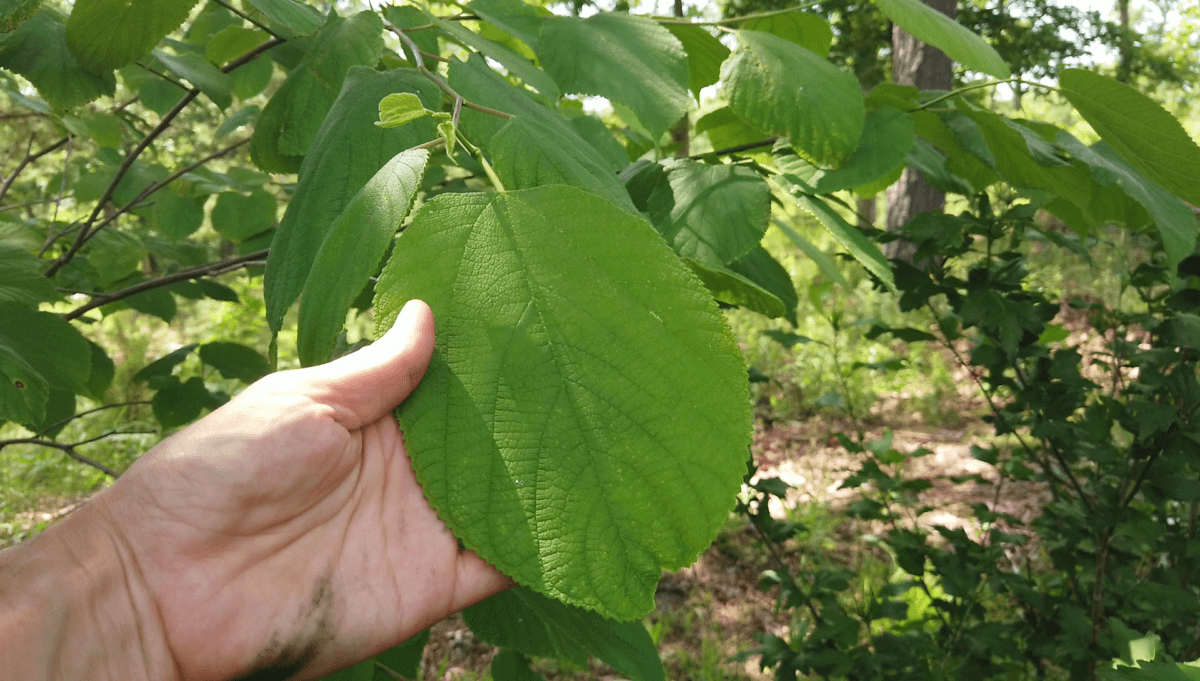

American mulberry (M. rubra) is a native species, often growing in the forest understory as a graceful, slender-limbed tree. The leaves have a fine grit sandpaper feel, with a distinctive sinus-step tooth in the hollows of the leaf-shape (if the leaf has lobes, that is) and often, an elongated tip.

It’s easy to confuse unlobed leaves before fruiting.

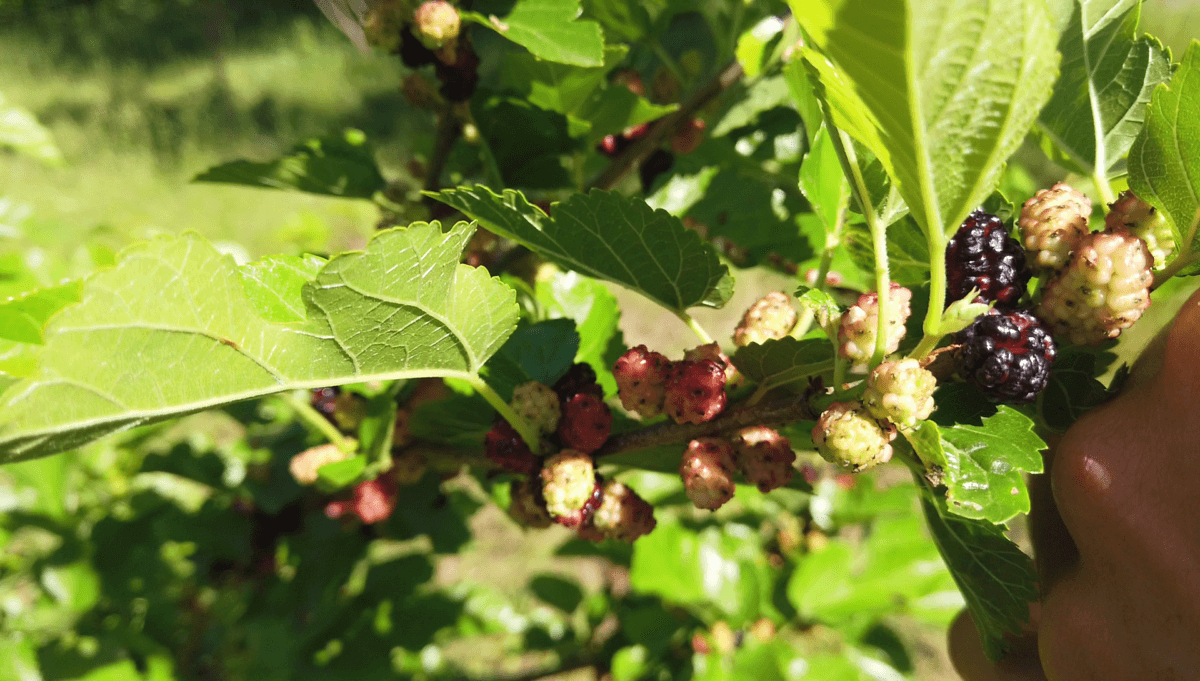

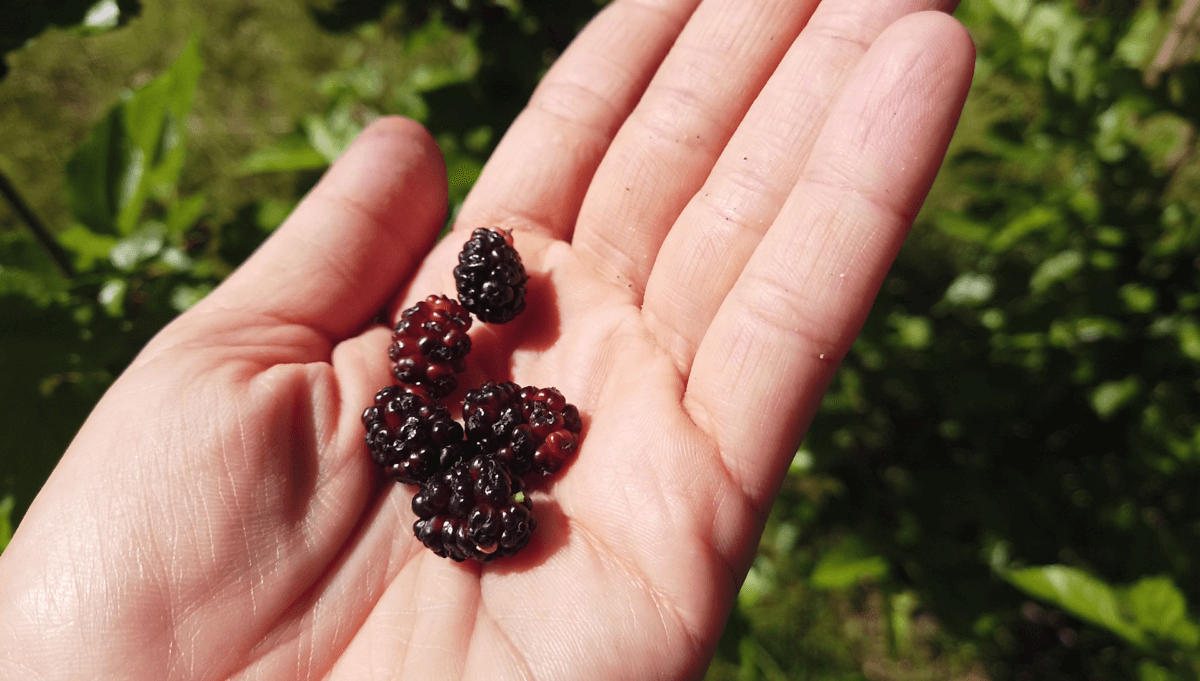

It produces dark purple fruit that is large and sweet.

The poorly-named white mulberry (M. alba) is an Asian species that was brought over as food for the silkworm industry and never really took off in the United States. Instead, it has naturalized to the point of becoming our most abundant mulberry species. Unlike American mulberry, it has smooth, shiny leaves that notably lack both that bitty “tooth” in the sinuses of the leaves and the elongated tip.

Its tree form is generally denser and more robust, especially if it’s growing in the open (which they often do). The fruit is a bit shorter than M. rubra, and despite its name, usually ripens to the same blue-black.

Occasionally, a specific tree will produce white or pinkish-white fruit, but most don’t. The taxonomist who named these Asian trees had only observed white-fruited trees at the time, christening them with a name that makes no sense in the long run. This confusion often leads folks to incorrectly identify black-fruited white mulberry as M. rubra, and identify the few white-fruited white mulberry trees as M. alba; totally deleting the true American mulberry from field guides and foraging books.

The confusion is so prevalent, that when we ordered American mulberry seedlings from our local department of conservation, they actually sent us the non-native Asian trees, mislabeled as M. rubra. I wasn’t aware of the mistaken identity until this year, when I realized a few of our 30 plus trees had white fruit. I took a closer look at their shiny leaves, and the truth was revealed.

For the forager, this mix-up doesn’t mean much. Both trees are similarly edible. Berries is berries, and in this case, they’re tasty from any tree. But for those who make a business in conservation, correct identification, or trying to reestablish native plant populations, it’s kind of a big deal. The mistakes I’ve seen in books, field guides, parks, and even my own orders for native plantings, are so prevalent it’s embarrassing. Furthermore, it’s scrubbing an entire species of native tree from our collective understanding.

Mulberries Look-Alikes

There’s really nothing that looks like a mulberry fruit, except a mulberry fruit. If you see blackberry-like fruit on a tree in early summer, it’s guaranteed that you’ve found the right tree. Isn’t it nice when things are that straightforward?

If the tree isn’t fruiting, it may be easy to confuse nonlobed mulberry trees with American basswood (Tilia americana) or slippery elm (Ulmus rubra). If it’s fruit you’re after, there’s no danger in this potential mix-up — those two trees won’t produce mulberries, obviously.

If it’s the edible leaves you’re after (more on that soon), there’s still little danger. Basswood leaves are similarly edible and delicious. And slippery elm leaves have a history of being used for tea, so there’s no toxic threat.

There should be no guessing in foraging, however — get acquainted with the distinctively asymmetrical base of a slippery elm leaf and you’ll be able to tell the difference between it and mulberry.

Harvesting Mulberries

Fruit: Mulberries fruit around the same time as wild strawberries near the end of May and through the first half of June. When these trees do produce, boy do they produce! You’ll find trees with abundant wild fruit, branches nearly obscured by generosity. The ripest fruits will usually be a deep purple-black color, though the white-fruited variants will be snowy white or pinky-tinged when ripe. Give a berry a taste to see if it’s good. You’ll know, once the sweetness hits you.

Though I see no need to hurry through a berry picking session, you can speed up the process by setting down a tarp and giving the branches a good shake. The ripe berries will rain down, usually with a helping of stink bugs and ants. Thankfully, mulberries float, making cleaning your wild haul a bit easier.

Leaves: A second product to be gathered from this tree are the edible shoots and leaves. Wait, you may be thinking, leaves? Tree leaves for food? What am I, a giraffe? (Well, you could play-act as one and strip a leaf or two off a standing tree, I suppose).

Mulberry trees have quite edible leaves. The young, green-branched shoots of spring are tender for a choice meal, but any leaf can be used. They’re tasty, don’t have any bitter flavor, and are abundantly available through the tree’s growing season. Both raw or cooked, you can use them as you would any other tender, enjoyable green. If eating raw, however, try to pick the youngest, most tender, bright-green leaves you can. Leaves that have fully matured may leave you chewing for longer than you want.

Beyond the salads or stir-fries, leaves can be dried and used for tea. Leaves have also been dried, ground, and added to flour as a nutritional amendment.

Cooking and Using Mulberries

For fresh eating, there’s little that can improve a fresh mulberry. Gather them by the handful or try them individually. You may be pleasantly surprised to find the range of flavors found from tree to tree. In my own little mulberry glade, for example, I have some trees that taste candy-like, while others have a more subtle sweetness. Just don’t judge a mulberry by the first bite. The next berry may taste different.

When cooked, however, they do sometimes leave a little to be desired. The first time I made a mulberry crumble, I mixed it with strawberries, and it was absolutely decadent. The second time I made a mulberry crumble, I made it with pure mulberry, and it was unremarkably bland. As I soon learned, the sweetness of the berries can be unbalanced when heated. I think it’s because they lack any noticeable acidity. If you combine mulberries with a nice, tart apple, a dash of lemon juice, or some fresh wild strawberries, it will make a world of improved difference. In his book Incredible Wild Edibles (which contains an excellent chapter on foraging mulberries), Samuel Thayer recommends mixing ripe and unripe fruit when making jams and preserves as an alternative way to balance the flavors.

If you can’t decide how to use your mulberry glut all at once, it’s super easy to freeze mulberries until you’re ready to use them.

Mulberries can be juiced, cooked into syrup, fermented or cooked into finger-staining chutneys, and pretty much used any way you would use any other berry. Some folks make a big deal about the little stems that stay stubbornly attached. I see it as a nonissue and don’t notice them. The fact that mulberries lack the hard-crunching seeds of other fruits like blackberries more than makes up for it. If they do bug you, though, cook down the fruit and send it through a food mill. That should clean it up nicely enough for your purposes.

So have you met a mulberry? If you haven’t, or if you’ve only noticed it when it stains the sidewalk bright purple in June, then I hope you fix the situation as soon as possible. They’re a great tree to add to your permaculture landscape, a wonderful friend to visit for a pick-me-up on the trail, and a multipurpose food source that anyone interested in self-sufficiency would do well to get acquainted with.

Photo/Attachment:

This was a great read, really informative. I live in Tallahassee, FL right now and they grow in abundance here, mostly wild. But I never see people feasting on these amazing berries. I feel sorry for them really. I am originally from Nepal and we call them mulberries “Kimbu” or with a slight vatiation “Kimmu”. We used to feast on them growing up. And all those times I had stomach ache eating those unripe ones, it was crazy. And when I saw them mulberries here in Florida growing everywhere, I recognised the plants when they were not even fruiting. And once they had fruits on them, I was a bit reluctant on trying them as I couldn’t be sure whether they were actually edible ones. But after enough internet rummaging, I concluded they were safe to eat. And the moment I tried the first one here, my taste buds immediately recognised those familiar flavors and brought all those memories back. They are literally everywhere here. I often go out on my bike and have a nice sweet and tarty feast. People do give me a kind of a weird look when they see me eating from this plant on the side of the road or a park. Thank you for the article.

The tree which I have eaten from has the LOBED AMERICAN MULBERRY LEAF, but the fruit looks like a very large raspberry (pinkish red) and it separates from the plant very easily. I have eaten many of these tasty berries; but after reading this article, I question whether it was a mulberry. Any thoughts on this? BTW, I live in upstate (central) NY.

Lovely trees with abundant fruit, but I would not bring one into my yard due to the ubiquitous stains it leaves on everything. Leave them in the wild and harvest them there unless you don’t mind purple paint over your entire yard and everything in it.