“Chestnuts roasting on an open fire …” is a phrase most Americans can sing along to without even thinking, but there is so much more to these amazing trees than Christmas lyrics. Much more than a seasonal treat, the chestnut tree has a fascinating history, a tragic past, and a deserving place on the homestead.

Would you like a stately, wide-spreading tree to fill a picturesque field? How about a rich source of nutrition that has been a staple food for cultures around the world? Would you like to try your hand at coppicing wood for some strong, rot-resistant timber? Or, are you interested in trying to revive an important species that has been nearly wiped out? Looks like it’s time to bring some chestnut trees into your life!

Chestnut Basics

Reducing a tree to its mere utility doesn’t do any tree justice, but when it comes to the chestnut tree, the many attractive attributes are hard to miss! Any homestead would benefit from their useful, rot-resistant hardwood, stately, broad-leaf stature, and delicious, edible nuts. American chestnut trees (and their close relatives, the chinquapin) also boast firework-like sprays of creamy early summer blossoms.

There are thirteen different species of chestnuts worldwide, usually categorized into four regional groups. The American, European, Chinese, and Japanese groups of trees attest to how widespread and culturally important these trees were and are as timber and sources of food.

The American species — most notably including the American chestnut, were also incredibly important to the Allegheny Mountains area as both a staple food for native people and a keystone food species for wildlife.

The starchy, sweet-from-the-tree seeds are unusual in the nut world because they are low in fat and high in carbohydrates. Before potatoes were introduced to Europe from the Americas, the nutrient-dense nuts were a staple for many forest-dwelling communities in Eastern Europe.

For centuries, these tasty nuts have been used in many world cuisines as everything from desserts and sweetmeats served to sultans on gilded platters, to simple, nourishing porridge that sustained peasants in lean times from Rome to Kyoto.

Related Post: Black Walnut Trees

Even in the modern day, European and Asian chestnuts are an important crop. In the Americas, however, this relevance is currently in the past tense because of the blight of the early 1900s. The tree is due for a major comeback as a useful crop to any homesteader with the foresight to give them a place on their acreage.

The Fall of Giants

No discussion of chestnut trees can occur without briefly delving into the tragedy of the American chestnut blight. If you were to walk the forests of the Appalachian United States in the mid-1800s, you wouldn’t recognize the place. Mind bendingly huge trees dominated the woods — sometimes as wide as 7 feet in diameter and 120 feet high.

These “redwoods of the east” were the dominant tree in the forests along the Appalachian Mountains, with one out of every four trees being an American chestnut. Check out this link to see historical photos of pre-blight chestnuts and prepare to have your mind blown — it truly was a different world.

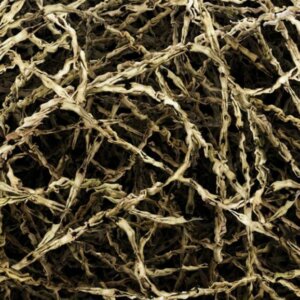

Around 1904 however, a blight arrived in the New York ports hidden among some Asian chestnut trees that were planted on Long Island. Though the Chinese varieties were immune to the fungus, the trees native to America were highly susceptible to the killing disease. The fungus invades the aerial portions of the tree’s inner bark, creating cankers — swollen, yellowish or reddish areas around the trunk — that can girdle and kill a tree within weeks.

Related Post: Pruning Apple Trees

Within the span of 50 years, every tree was dead where it stood. Though some rare, isolated individuals have been discovered in the post-blight era, the age of forests dominated by this important, beneficial tree are at an end. At least, for now.

Though the blight wiped out nearly every American chestnut tree, the species is not done for yet. Indeed, your homestead could be a part of bringing chestnut trees back into the daily lives of people who could re-learn how to benefit from its useful wood and delightful fruit.

Chestnut Tree Varieties

Growing a 100% original American chestnut tree will probably end in disappointment, as the chestnut blight is still widespread across the United States and here to stay. “Pure” American chestnut trees grow for about 5 to 10 years or so, and then succumb to the disease and die.

Several blight-resistant strains have been developed over the past few decades, however, through a breeding process called “back-crossing.” Crossed with Chinese chestnuts, then hybridized back with American chestnuts, blight-resistant hybrids are available that display the tall stature of the American species with the vigor of the Chinese varieties, and they are very likely to thrive and produce nuts.

As with any domesticated variety of plant, there is quite a wide array of varieties. This list is just a sampling, but it provides some jumping-off points for the prospective tree-farmer.

Related Post: How to Create a Tree Nursery

Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima)

A medium-sized tree (around 40 feet tall), wide-spreading and multi-branched, with good tolerance to blight. They grow large, sweet nuts. Consider the Qing or super-cold hardy Mossbarger varieties.

European Chestnut (Castanea sativa)

Sometimes called sweet chestnut, it is not as cold-hardy as the Chinese chestnut, and potentially susceptible to blight. Grows taller (around 65 feet tall). Consider the Italian Bracalla variety for cooler climates.

Japanese Chestnut (Castanea crenata)

A small to medium-sized tree (around 30 feet) that is neither winter-hardy or blight resistant. Often used on the west coast of the U.S. where climates are more suited to their needs, and the blight is not as widespread. Very often used to create hybrids.

American Chestnut (Castenea dentata)

Both cold-hardy and huge-growing, this is the former giant of the Appalachians. Totally blight-susceptible in unhybridized form. Consider the blight-resistant (though not immune) Dunstan hybrid (crossed with C. molissima) or the Eaton River variety (a hybrid of Chinese with a Japanese/American hybrid).

On our homestead, we opted to plant an American-Chinese hybrid. To be honest, we don’t want to have our tree-planting efforts foiled in 10 years by the emergence of blight, and we are hoping to harvest bucket loads of the Chinese chestnut’s huge nuts. On our homestead, we’re hoping to use the trees as a food source, so our goals are oriented toward a harvest (not a revival of a species). You may feel differently on your homestead, so do your research and make the decision that is best for you.

Note: While researching chestnuts, you will inevitably see folks start mixing up the horse chestnut genus (Aesculus) with the true chestnut genus (Castanea). Even websites that discuss the Castanea will sometimes use the wrong photos, even though the leaves are totally different. This can be a problem for those looking to enjoy the nuts — horse chestnuts and their relatives are poisonous!

Related Post: Growing Peanuts

The seeds have a vaguely similar appearance, though the spines of true chestnuts are far finer than the thorn-like spikes of the horse chestnuts. Before you go on a nut-collecting venture, be sure to familiarize yourself with the palmate leaves of the Aesculus and the simple leaves of the Castanea so that you can avoid any mix-ups.

Growing Conditions and Location

When it comes to selecting the perfect spot for your chestnut tree, there are several factors to keep in mind. The first is that these trees can be BIG. A mature American chestnut grows straight and noble and tall. It is able to reach a height of 100 feet — though if you’re planting it in your lifetime, you probably won’t see that immense size.

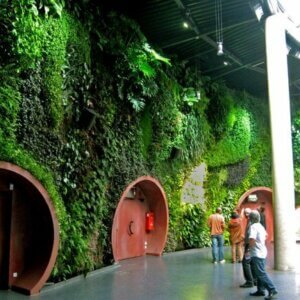

If planted in a nice, sunny spot, the trees develop an attractively domed crown. The Chinese and Japanese varieties develop in to equally attractive (though not as tall) forms, usually creating a picturesque, multi-leader tree.

These trees benefit from locations with all four seasons and are hardy all the way to hardiness zone 5. Chestnut trees do best on well-drained, acidic soil with plenty of sunlight. If you live in alkaline soil, you may have success with chestnut trees that are grafted onto an oak rootstock as oaks are near relatives. Deep, sandy soils are ideal, but clay soils may work if the tree is planted on a slope.

Related Post: Dwarf Fruit Trees

When planting your new trees, do them a favor and clear all the grass out from around their roots. Unlike the beneficial plants you could choose to plant there like comfrey, dill, or nasturtium, grass merely robs nutrients from your saplings.

In order to bear fruit, you need at least two trees. Though a single tree produces both male and female parts, they need to be pollinated by a separate individual. Be sure to plant them well enough apart that they don’t touch in adulthood, however. We chose a sunny location on the top of one of our hills and dedicated it to five chestnut trees, all of them at least 60 feet apart.

Finally, have a plan for your young trees as soon as you get them in the ground. If you leave them to grow wild, they will probably grow fine enough, but with careful management of branches, they’ll be even healthier and more productive.

Related Post: 7 Indoor Trees to Add Some Greenery to Your Home

Thoughtful pruning and training of chestnut trees should be done when they are young. The older they get, the harder it will be to manage them. Creating a nice, clear trunk through careful management will lead to a healthier, easier-to-care-for tree in the long run! Check out this helpful pdf for more information.

Diseases to Watch For

The biggest disease to watch out for in your chestnut trees, is, of course, the killing cankers of the chestnut blight fungus. If you have chosen to plant Chinese varieties of the tree, you’ll not need to worry about it as much, as they are typically blight-resistant.

American hybrids and European varieties may still be susceptible, so keep a close eye on your newly-planted trees. There’s no curing blight, so if it strikes your trees, the best plan is to take a deep breath, wipe your tears, and start over with a new cultivar.

Sunscald may also bother your chestnut trees, with the unfortunate similarity in appearance to a blight canker. This is the equivalent of the tree getting sunburn and is often caused by super-strong sunlight hitting the bark. Sometimes, this is caused by over-pruning the tree. Prevention through careful management, seasonal trunk-wrapping, and careful planting, is the best treatment for this unsightly problem because once the tree has it, it’s not going to go away.

Leaf spot is another common affliction of chestnut trees, but the resulting yellowed and brown leaves is largely a cosmetic issue. A good way to manage this bacterial or fungal infection is to practice prevention and good tree maintenance — remove fallen leaves from around the tree every fall (this is where the pathogens overwinter) and provide the trees with a thick layer of beneficial mulch.

Harvesting the Bounty

Trees may start producing delicious nuts as early as 3 years old, but I think a more reliable estimate may be to expect nuts by the time they’re at least 7 years old. You’ll want to wear sturdy shoes and maybe even some gloves because the spines on the nut’s hulls don’t mess around!

Once you have done all the hard work to get your chestnut trees to produce, the rest of the adventure is up to you. There is truly nothing more wonderful smelling than chestnuts roasting with a little knob of butter tucked into every nut. Hopefully, one day you’ll get to revive that wonderful winter memory with your children.

Are any of you growing your own chestnut trees? What variety are you trying to grow, and what got you interested in growing them in the first place? Do any of you have stories from your grandparents about the days when chestnuts and chinquapins were plentiful? Let me know in the comments below!

I have recently started growing american chestnuts from seed. Also timber hybrids from seed. Must move these to northern wisconsin. Zone 3b/4a. My southern Wisconsin home is way to alkaline and clay like for the chestnuts.

Also bought a few young seedlings. So far one tree has 2 years of male catkins but no female flowers yet.

I am growing hybrid trees in southeast Ohio in the Appalachian foothills. I have been planting additional trees each year it my open canopy woodlands. I hope to select trees that do better in the forest.

The hills area needs cash crops that can be grown without soil loss on the steeper slopes. We have a local team that is creating chestnut orchards on old depleted farmlands.

Hi, where can I get what I need to grow chestnuts? I am in Ky and want to replace a 20 acre field with chestnut tree rows. Michael

Hi, where can I get what I need to grow chestnuts? I am in Ky and want to replace a 20 acre field with chestnut tree rows. Michael

Hello, I am In North Yorkshire, and have just planted some European chestnuts gathered from woodland near my family home in Somerset. They’re in a mixture of leafmould and John Innes no.2 and I’m hoping some of them will germinate.

Will Chestnut trees survive in the Parry Sound/McKellar area (ont)? If so where can I purchase a Chestnut Tree?