“Eat more healthy! Eat organic leafy greens!” The bleached-smile exhortations of the nutritional elite ring out from websites and health shows. So we trundle over to the grocery store and are greeted by the sight of an $8 bundle of organic spinach that would barely feed a rabbit — much less a whole family. Then we grumble to Twitter, repeating the common line that it’s just not financially possible for us to buy those health foods.

We mumble through mouthfuls of “food” from a Burger-World paper sack that it’s not our fault we can’t afford ridiculously priced, real food. Not everyone has an organic farm in their backyard; not everyone has a 6-figure salary that can support a green smoothie habit. Not everyone can eat healthy.

Hold up! This whole story, familiar as it may sound, is a fallacy embodied. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Watch the Video

Yes, we need to eat more leafy, organic greens. Many of our American dinner plates are painfully, tragically devoid of nutrition and the tradition of cooking greens as a daily part of our diet. And yes, we need to eat organic ones — as the pesticides coating the surfaces of commercial veggies are nothing to ignore. But no, they are not prohibitively expensive — not all of them. And no, your only other option for a full stomach is not prepackaged garbage masquerading as nutrition. Real food is not more expensive than fast food. You just have to think outside the takeout box (and outside the grocery store box) because some of the best, most nutritious, and widely available foods are right outside your door, absolutely free for the taking.

Enter wild spinach.

Wild spinach is a weed that knows no socioeconomic bounds. It grows among the fancy cultivated tea roses in the gated community and fills the abandoned lots of the city. It’s probably growing in your garden or next to the sidewalk right now. When I lived in a poor city neighborhood, I allowed this wonderful plant to take over much of my postage stamp of a backyard, and in return, it fed me and my family countless meals for free. Now, when I find it on our homestead, it’s a familiar friend … even when (annoyingly) pushing past my seedling corn.

I’d like to introduce you to this abundant weed. I bet you’ve met it before, but had no idea it was food. Let’s fix that!

Finding and Identifying Wild Spinach

Chenopodium album is a plant of a dozen common names — this is one of the many reasons why knowing the scientific name of a plant is imperative when it comes to identifying it correctly. I’ll be referring to it as wild spinach for the purposes of this article, but you’ll also find this plant called lamb’s quarters, goosefoot, pigweed, bacon weed, melde, bathua, frost-blite, or fat hen, to name a few. I take its multitude of titles as a marker of how useful this plant has been in the past for humans and animals alike.

Chenopodium album is found pretty much anywhere across the United States. Though C. album, the feature plant of this article, is listed as a debatably European weed (it’s been in cultivation so long nobody’s really sure of its origin), it is very closely related with C. berlandieri, a native plant that was used as a food and grain source by Native American Nations for thousands of years. These plants also hybridize and have incredibly diverse forms. So all that to say — it’s not going anywhere anytime soon, and you’ll not need to worry about overharvesting when you find a decent patch of it. Pluck those leaves at will.

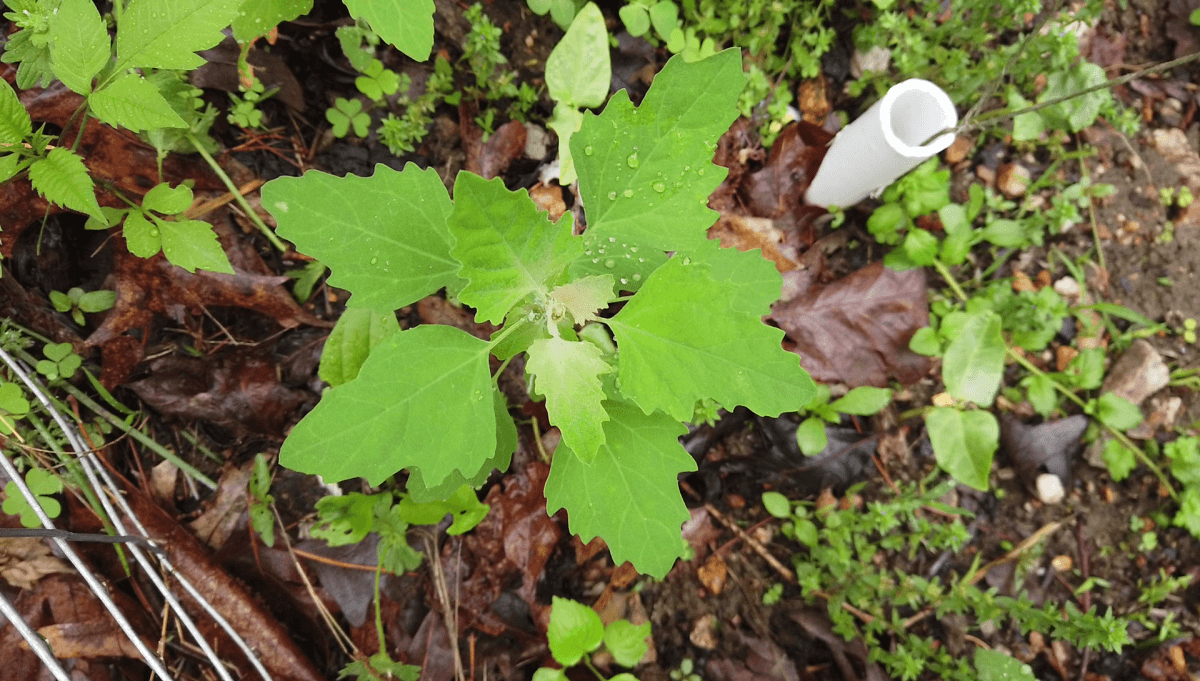

Wild spinach is a summer plant, growing in abundance as the mercury rises and the sun blazes. It endures, too, growing all the way until the leaves start to fall. In my personal foraging calendar, it graciously takes up the greens-for-dinner mantle once pokeweed has started to mature. It’s typically found in sunny places where the soil has been disturbed. This is a huge list of areas including river bottoms, sun-soaked slopes, construction sites, any garden plot, crop fields, backyards, semi-arid areas, pastures, abandoned lots, and areas disturbed by recent floods.

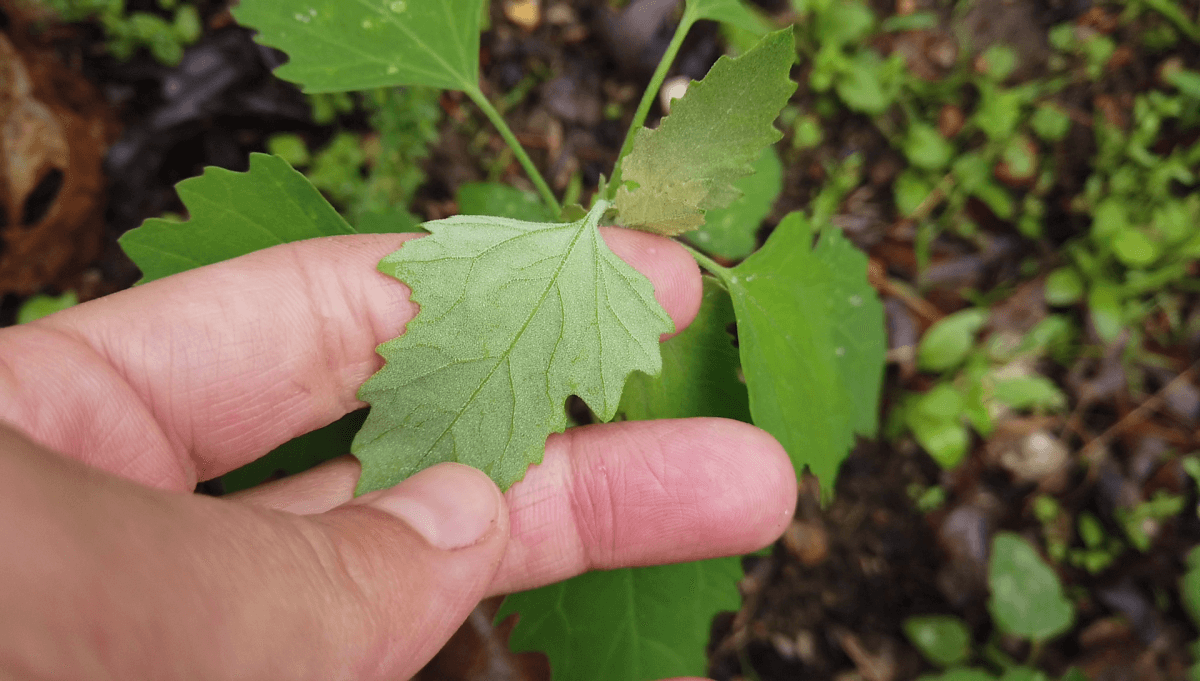

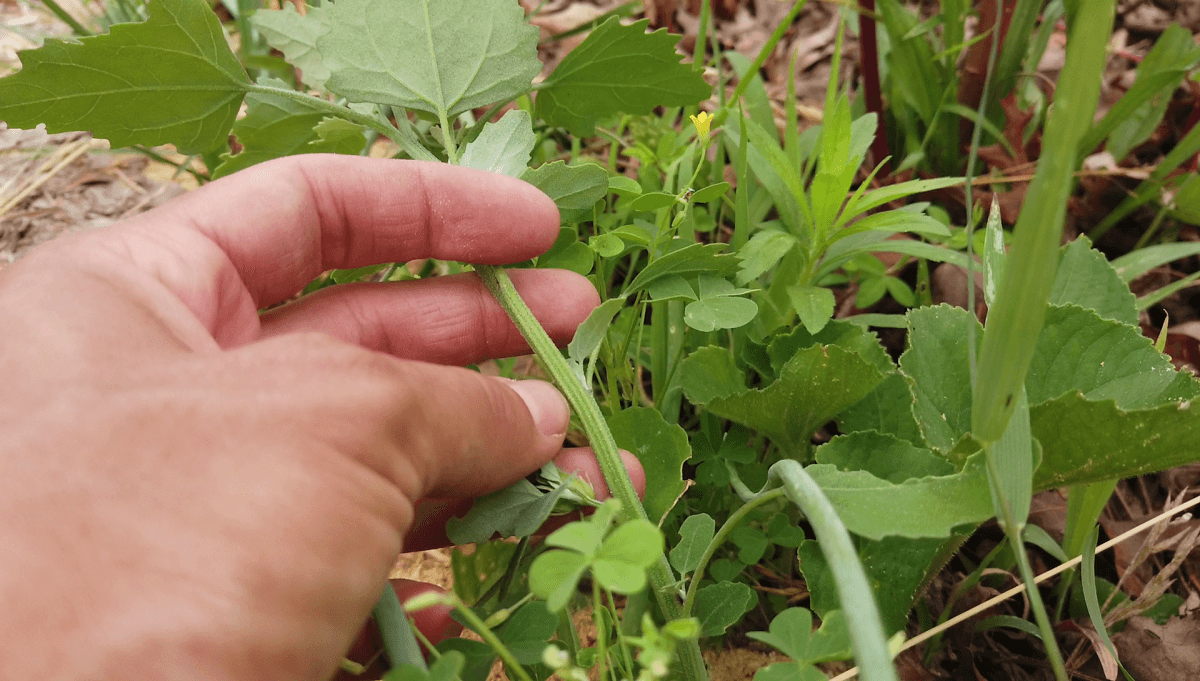

In appearance, I find the plant to be distinctive. The leaves alternate, growing on a striped stem that often has a bit of red where the leaves join with it. The leaves grow in a vaguely arrowhead shape with wide teeth or lobes along their edges. As with most plants, those growing in direct sunlight will have more sculpted edges than those growing in partial shade. And most distinctively, the undersides of the bluish-green leaves are coated with an unmistakable whitish powder — it will rub off on your fingers if you touch it, giving the leaves a distinctively gritty feeling. The powder is harmless and rubs off when you wash the plant for consumption, but it’s a key characteristic. You’ll especially find this white powder on the leafy tips of a branch where new growth is forming. Aside from helping with identification, this powdery layer makes dew drops bead beautifully on wild spinach leaves. Grab your macro lens and get some gorgeous early morning photography, if you happen upon it.

If you catch the plant growing in early summer, it may be only a foot tall. That’s usually when you find it peeking between the tomatoes in your garden. But left unmolested, it will easily grow between 3 and 5 feet tall, and up to 7 feet in optimal growing conditions.

As the plant matures, it branches out and begins creating its underwhelming flower stalks. The flowers are tiny and unremarkable, but they produce tons of little black, shiny seeds. Upon close inspection, some people may notice that they bear a remarkable similarity to quinoa. And in fact, that recently popular Andean grain is also part of the Chenopodium genus.

In the fall, the plants turn a lovely fire red before they die. This is usually when the seeds are ripe and falling. Grab a handful of the abundant, bitty grains and spread them where you want to find a haul of wild spinach next year.

Look-Alikes

To my knowledge, there aren’t any problematic look-alikes for wild spinach. The only plants I’ve found that have a similar appearance are other just-as-edible members of the Chenopodium genus. Though C. album is probably the most widespread, those who live in the eastern United States will likely also encounter C. hybridium, the maple-leaved goosefoot. This species is more tolerant of shade, often growing in hardwood forests. It also lacks the distinctive whitish powder on its leafy undersides, but is nonetheless, just as edible and useful. There are many other members of this genus that are locally abundant across the United States. As you grow in botanical literacy, check your local flora guides for the Chenopodium plants that grow in your region.

Note: Samuel Thayer mentions in his book The Forager’s Harvest, that Mexican tea and epazote may be unsafe to eat in quantity. Apparently, they have a strong smell and look quite different from other similar plants (and have been reclassified as Dysphania ambrosioides).

Harvesting Wild Spinach

In the late spring and early summer, you can harvest the entire plant. The stem should be tender enough by that point to not pose a problem in your finished dish. Once the heat of summer sets in and the plant really takes off growing, however, the main growing stem will quickly become way too tough to eat, or even break easily. The leaves, no matter what stage, however, are always prime pickings.

Plucking individual leaves from 5-foot plants is incredibly tiresome, however. So, I’ll share my method of harvesting buckets of greens in short order. If you want to leave the plant standing to produce seeds later on, hold the tender growing tip in one hand to keep the branch taught, then, skipping that first tuft of leaves, run your closed hand down the length of the stems. The leaves and tender little branches will snap off effortlessly.

If you’re cleaning out plants from the garden and already ripped them out, you just need to run your fist against the grain of the plucked stem — laying them on a picnic table will make it easy to get things organized. After you’ve twisted off the tender growing tip as well, place handfuls of greens in your bag or basket, and throw the cleaned stems in the compost pile. Within minutes, you’ll have a heap of food for dinner.

The one safety note I have concerning wild spinach has nothing to do with the plant itself, but with its growing environment. As a mineral-rich green, this plant uptakes all its abundant nutrition from the soil. This fascinating feature makes wild spinach a useful plant in bioremediation experiments, as it is able to remove heavy metals from the soil naturally. But it also means that plants growing in contaminated ground are, themselves, contaminated. When you gather your wild spinach, therefore, vet the environment and make a judgement call about whether or not it’s polluted. Plants growing in your garden or yard are fine, and plants growing in an abandoned lot in the city are probably alright too, but plants growing around a dump, parking lot, or otherwise industrialized area are probably not safe for consumption.

I should mention that the seeds, being quinoa relatives, are edible as well. I should also mention, however, that I’ve never gone through the process of collecting enough to merit cooking them. The seeds of C. album are tiny and a bit fiddly to free from their calyxes — at least with the methods I’ve tried. My inexperience in this department should not stop you, though. There are archaeological records indicating that different Native Americans did gather and consume the seeds as a grain. I would love to have known their process.

There are also different species of Chenopodium plants that have different-sized seeds. The maple-leaved goosefoot in particular, has much bigger seeds, but since it doesn’t grow in my area, I haven’t gotten to mess around with it. If any of you have experience with using this underutilized food source, please share your know-how with us below! And in the meantime, you can check out Ashley’s endeavors using water to winnow C. album grain at her website: Practical Self Reliance.

Cooking Wild Spinach

Wild spinach is a perfect spinach substitute, and you can use it in any and every way that you would the conventional stuff. Raw, wilted, or fully cooked, it is as versatile as it is delicious. I actually prefer wild spinach to cultivated spinach, as I find it doesn’t give me that minerally weird, tooth-squeaky feeling that I often get when eating store bought leaves. Instead, the flavor, while mild, is unmistakably green and hearty with a very wild floral note. And the nutrition can’t be beat. I don’t give much stock to nutritional analyses of wild greens as they vary so widely according to their environments, but if these numbers here are anything close, it’s safe to assume that wild spinach is full of good stuff your body needs.

If you’re accustomed to cooking wild greens, you’ll not have any trouble coming up with ideas for this abundant food source. But if you’re feeling a little unsure, here are some easy ways to use one of my favorite, summer wild foods.

One of the easiest is to throw a handful of cleaned leaves into whatever you’re cooking at the time. The first handful of this summer’s wild spinach harvest, for example, was washed and tossed into an Italian-style stew, and served alongside eggs and corn pones. The leaves cook down quickly, adding their color and nutrition without swerving the flavors. Wild spinach is also amazing stir-fried with ginger and garlic or thrown into an omelet with cheese.

A simmered and blended wild spinach paste is also an incredibly versatile ingredient. Add it to soups, blend it with eggs and spices and bake it in a pie crust, or add tomatoes, olive oil, and garlic to make a verdant and bright pasta sauce.

My absolute favorite way to use wild spinach, however, is in a wild version of palak paneer — those delectable homemade cheese cubes swimming in a fragrantly spiced green gravy. I’ll be detailing my recipe (along with others) in an upcoming article, so stay tuned!

And true to its name, “fat hen” wild spinach is relished by chickens. But once you figure out how tasty and useful it is, you may have a hard time sharing it with them.

Most people have seen this weed and having it growing somewhere nearby, and I’d wager that a majority of them have no idea it is food. Can you imagine the healthful impact of adding this one, healthful, easy-to-identify and easy-to-cook green to everyone’s knowledge base? That pile of overpriced spinach at the grocery store would stop holding so much esteem, that’s for sure. And maybe the misconception that healthy food is the privilege of the well-off would lose its edge as well.

Good food is everywhere, and available to everyone who has the eyes to see it. I hope that you make acquaintances with Chenopodium album. It’s a good friend to know!

If it’s the same one with which I’m familiar, I used to eat this stuff as a kid in Iowa. We called it “lamb’s tongue” and it tastes just like spinach.

I harvested this in Forestville, CA from volunteers along a garden fence.

I so love the freshness and mild flavor and I agree with a comment that it doesn’t have that odd that minerally weird, tooth-squeaky feeling.

© Foraging for Wild Spinach • Insteading

Source: https://insteading.com/blog/foraging-for-wild-spinach/